I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on the different definitions on inverse functions that appear in Precalculus and Calculus.

Square Roots, nth Roots, and Rational Exponents

Part 1: Simplifying

Part 2: The difference between and solving

Part 3: Definition of an inverse function and the horizontal line test

Part 4: Why extraneous solutions may occur when solving algebra problems involving a square root

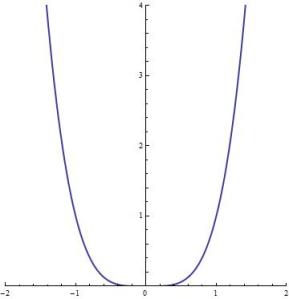

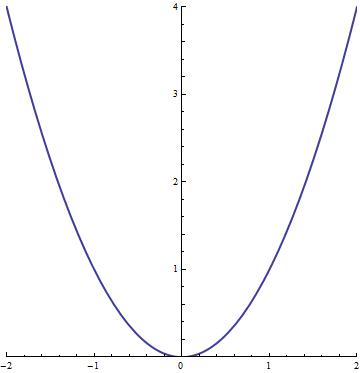

Part 5: Defining

Part 6: Consequences of the definition of : simplifying

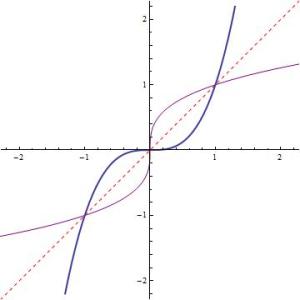

Part 7: Defining if

is odd or even

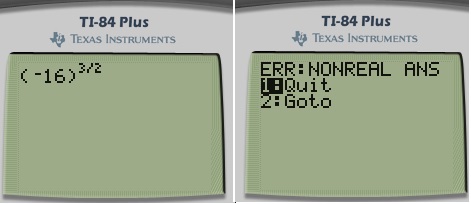

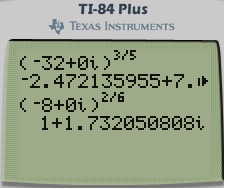

Part 8: Rational exponents if the denominator of the exponent is odd or even

Arcsine

Part 9: There are infinitely many solutions to

Part 10: Defining arcsine with domain

Part 11: Pedagogical thoughts on teaching arcsine.

Part 12: Solving SSA triangles: impossible case

Part 13: Solving SSA triangles: one way of getting a unique solution

Part 14: Solving SSA triangles: another way of getting a unique solution

Part 15: Solving SSA triangles: continuation of Part 14

Part 16: Solving SSA triangles: ambiguous case of two solutions

Part 17: Summary of rules for solving SSA triangles

Arccosine

Part 18: Definition for arccosine with domain

Part 19: The Law of Cosines and solving SSS triangles

Part 20: Identifying impossible triangles with the Law of Cosines

Part 21: The Law of Cosines provides an unambiguous angle, unlike the Law of Sines

Part 22: Finding the angle between two vectors

Part 23: A proof for why the formula in Part 22 works

Arctangent

Part 18: Definition for arctangent with domain

Part 24: Finding the angle between two lines

Part 25: A proof for why the formula in Part 24 works.

Arcsecant

Part 26: Defining arcsecant using

Part 27: Issues that arise in calculus using the domain

Part 28: More issues that arise in calculus using the domain

Part 29: Defining arcsecant using

Logarithm

Part 30: Logarithms and complex numbers