Last summer, Math With Bad Drawings had a nice series on the notion of infinity that I recommend highly. This topic is a perennial struggle for math majors to grasp, and I like the approach that the author uses to sell this difficult notion.

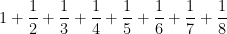

Here’s Part 2 on the harmonic series, which is extremely well-written and which I recommend highly. Here’s a brief summary: the infinite harmonic series

diverges. However, if you eliminate from the harmonic series all of the fractions whose denominator contains a 9, then the new series converges! This series has been called the Kempner series, named after the mathematician who first published this result about 100 years ago.

Source: http://smbc-comics.com/index.php?id=3777

To prove this, we’ll examine the series whose denominators are between 1 and 8, between 10 and 88, between 100 and 888, etc. First, each of the terms in the partial sum

is less than or equal to  , and so the sum of the above eight terms must be less than

, and so the sum of the above eight terms must be less than  .

.

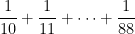

Next, each of the terms in the sum

is less than  . Notice that there are

. Notice that there are  terms in this sum since there are 8 possibilities for the first digit of the denominator (1 through 8) and 9 possibilities for the second digit (0 through 8). So the sum of these 72 terms must be less than

terms in this sum since there are 8 possibilities for the first digit of the denominator (1 through 8) and 9 possibilities for the second digit (0 through 8). So the sum of these 72 terms must be less than  .

.

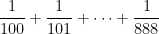

Next, each of the terms in the sum

is less than  . Notice that there are

. Notice that there are  terms in this sum since there are 8 possibilities for the first digit of the denominator (1 through 8) and 9 possibilities for the second and third digits (0 through 8). So the sum of these

terms in this sum since there are 8 possibilities for the first digit of the denominator (1 through 8) and 9 possibilities for the second and third digits (0 through 8). So the sum of these  terms must be less than

terms must be less than  .

.

Continuing, we see that the Kempner series is bounded above by

Using the formula for an infinite geometric series, we see that the Kempner series converges, and the sum of the Kempner series must be less than  .

.

Using the same type of reasoning, much sharper bounds for the sum of the Kempner series can also be found. This 100-year-old article from the American Mathematical Monthly demonstrates that the sum of the Kempner series is between  and

and  . For more information about approximating the sum of the Kempner series, see Mathworld and Wikipedia.

. For more information about approximating the sum of the Kempner series, see Mathworld and Wikipedia.

It should be noted that there’s nothing particularly special about the number  in the above discussion. If all denominators containing

in the above discussion. If all denominators containing  , or any finite pattern, are eliminated from the harmonic series, then the resulting series will always converge.

, or any finite pattern, are eliminated from the harmonic series, then the resulting series will always converge.

.

.

.

.

.

.