Which answer is simplified: or

? From example, here’s a simple problem from trigonometry:

Suppose

is an acute angle so that

. Find

.

To solve, we make a right triangle whose side opposite of has length

and hypotenuse with length

. The adjacent side has length

. Therefore,

This is the correct answer, and it could be plugged into a calculator to obtain a decimal approximation. However, in my experience, it seems that most students are taught that this answer is not yet simplified, and that they must rationalize the denominator to get the “correct” answer:

Of course, this is equivalent to the first answer. So my question is philosophical: why are students taught that the first answer isn’t simplified but the second is? Stated another way, why is a square root in the numerator so much more preferable than a square root in the denominator?

Feel free to correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems to me that rationalizing denominators is a vestige of an era before cheap pocket calculators. Let’s go back in time to an era before pocket calculators… say, 1927, when The Jazz Singer was just released and stars of silent films, like Don Lockwood, were trying to figure out how to act in a talking movie.

Before cheap pocket calculators, how would someone find or

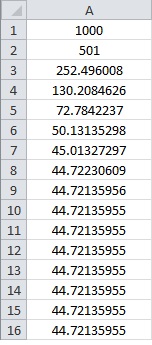

to nine decimal places? Clearly, the first step is finding

by hand, which I discussed in a previous post. So these expressions reduce to

or

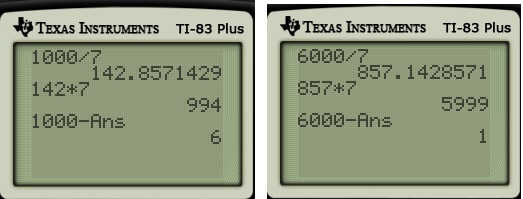

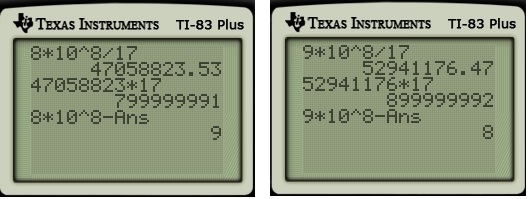

Next comes the step of dividing. If you don’t have a calculator and had to use long division, which would rather do: divide by or divide by

?

Clearly, long division with is easier.

It seems to me that ease of computation was the reason that rationalizing denominators was required of students in previous generations. So I’m a little bemused why rationalizing denominators is still required of students now that cheap calculators are so prevalent.

Lest I be misunderstood, I absolutely believe that all students should be able to convert into

. But I see no compelling reason why the “simplified” answer to the above trigonometry problem should be the second answer and not the first.

A report of the General Accounting office,

A report of the General Accounting office,