I really enjoyed reading a recent article on Math With Bad Drawings centered on solving the following problem without a calculator:

I won’t repeat the whole post here, but it’s an excellent exercise in numeracy, or developing intuitive understanding of numbers without necessarily doing a ton of computations. It’s also a fun exercise to see how much we can figure out without resorting to plugging into a calculator. I highly recommend reading it.

When I saw this problem, my first reflex wasn’t the technique used in the post. Instead, I thought to try the logic that follows. I don’t claim that this is a better way of solving the problem than the original solution linked above. But I do think that this alternative solution, in its own way, also encourages numeracy as well as what we can quickly determine without using a calculator.

Let’s get a common denominator for the two fractions:

and

and  .

.

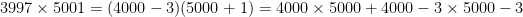

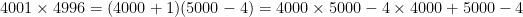

Since the denominators are the same, there is no need to actually compute  . Instead, the larger fraction can be determined by figuring out which numerator is largest. At first glance, that looks like a lot of work without a calculator! However, the numerators can both be expanded by cleverly using the distributive law:

. Instead, the larger fraction can be determined by figuring out which numerator is largest. At first glance, that looks like a lot of work without a calculator! However, the numerators can both be expanded by cleverly using the distributive law:

,

,

.

.

We can figure out which one is bigger without a calculator — or even directly figuring out each product.

- Each contains

, so we can ignore this common term in both expressions.

, so we can ignore this common term in both expressions.

- Also,

and

and  are both equal to

are both equal to  , and so we can ignore the middle two terms of both expressions.

, and so we can ignore the middle two terms of both expressions.

- The only difference is that there’s a

on the top line and a

on the top line and a  on the bottom line.

on the bottom line.

Therefore, the first numerator is the larger one, and so  is the larger fraction.

is the larger fraction.

Once again, I really like the original question as a creative question that initially looks intractable that is nevertheless within the grasp of middle-school students. Also, I reiterate that I don’t claim that the above is a superior method, as I really like the method suggested in the original post. Instead, I humbly offer this alternate solution that encourages the development of numeracy.

.