In yesterday’s post, we saw that restricting the domain of to

permits the definition of

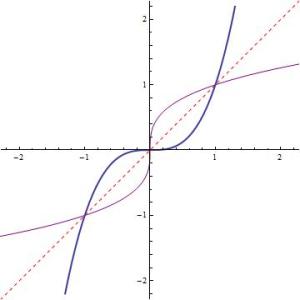

, shown in the purple graph.

Today, I want to give some pedagogical thoughts on teaching this concept to Preaclculus students.

Today, I want to give some pedagogical thoughts on teaching this concept to Preaclculus students.

1. Notice that, if the purple graph was completed upward or downward, anything more than a half-period would violate the vertical line test and thus fail to be a function. Thinking back to the original function, that’s another way of saying that the original sine wave violates the horizontal line test.

2. Restricting the domain to was a perfectly arbitrary decision. As shown above, there are plenty of other domains that would have worked acceptably. Only tradition requires us to choose

. (By the way, finding an expression for the restriction of

to, say,

is a standard problem in a first course in real analysis.)

3. Since is typically used as shorthand for

, some students will make the natural mistake of thinking that

is just shorthand for

, or

. So I like to address this head-on when introducing inverse trigonometric functions for the first time to my Precalculus students.

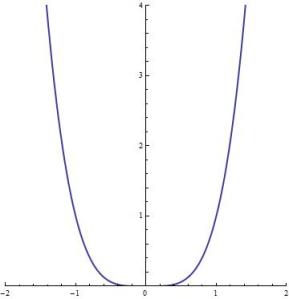

4. Unlike other inverse functions, it can be a little tricky for students to draw the graph of by hand because the line of reflection

actually is the linearization of

at

. In other words,

is the first term of the Taylor series of

at

. (For more details, see https://meangreenmath.com/2013/07/24/taylor-series-without-calculus-2/ or https://meangreenmath.com/2013/07/06/reminding-students-about-taylor-series-part-6/) Therefore, as seen in the picture, the line

is very, very close to the graph of

for

.

To assist students with accurately drawing by hand the graph of , I point out that the original function

levels off horizontally at the points

and

. Therefore, after reflecting through the line

, the graph of

enters almost vertically through the points

and

.

5. Most Precalculus students are not savvy enough to appreciate the nuances of domain and range in the above definitions. Therefore, after illustrating the importance of choosing an interval that satisfies the horizontal line test, I’ll give the following ways of remembering what means:

“Arcsine of is an angle. It is the angle whose sine is equal to

. And it’s the angle that lies between

and

.

OR

means that

and

.

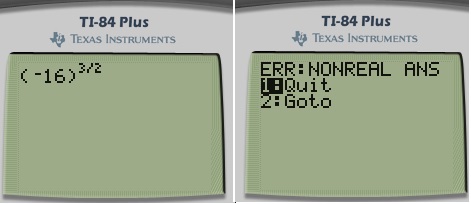

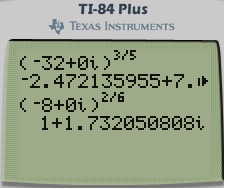

6. Since and

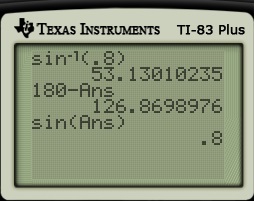

are inverse functions, it’s always true that

and

. However,

and

are not inverse functions, where

is the full sine function

. Therefore, it’s possible for

to be something other than

. For example,

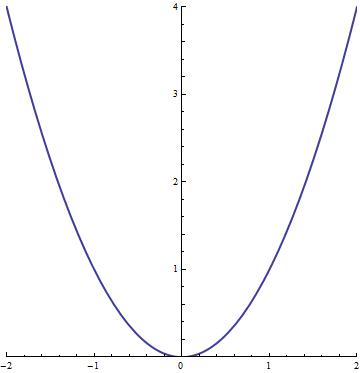

This is analogous to our earlier observation involving the square root function, which was also defined by a restricted domain:

.