The following problem appeared on the American High School Mathematics Examination (now called the AMC 12) in 1988:

If  , what is

, what is  ?

?

When I presented this problem to a group of students, I was pleasantly surprised by the amount of creativity shown when solving this problem.

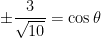

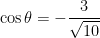

Yesterday, I presented a solution using a Pythagorean identity, but I was unable to be certain if the final answer was a positive or negative without drawing a picture. Here’s a third solution that also use a Pythagorean trig identity but avoids this difficulty. Again, I begin by squaring both sides.

Yesterday, I used the Pythagorean identity again to find  . Today, I’ll instead plug back into the original equation

. Today, I’ll instead plug back into the original equation  :

:

Unlike the example yesterday, the signs of  and

and  must agree. That is, if

must agree. That is, if  , then

, then  must also be positive. On the other hand, if

must also be positive. On the other hand, if  , then

, then  must also be negative.

must also be negative.

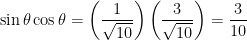

If they’re both positive, then

,

,

and if they’re both negative, then

.

.

Either way, the answer must be  .

.

This is definitely superior to the solution provided in yesterday’s post, as there’s absolutely no doubt that the product  must be positive.

must be positive.

,

,

.