In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

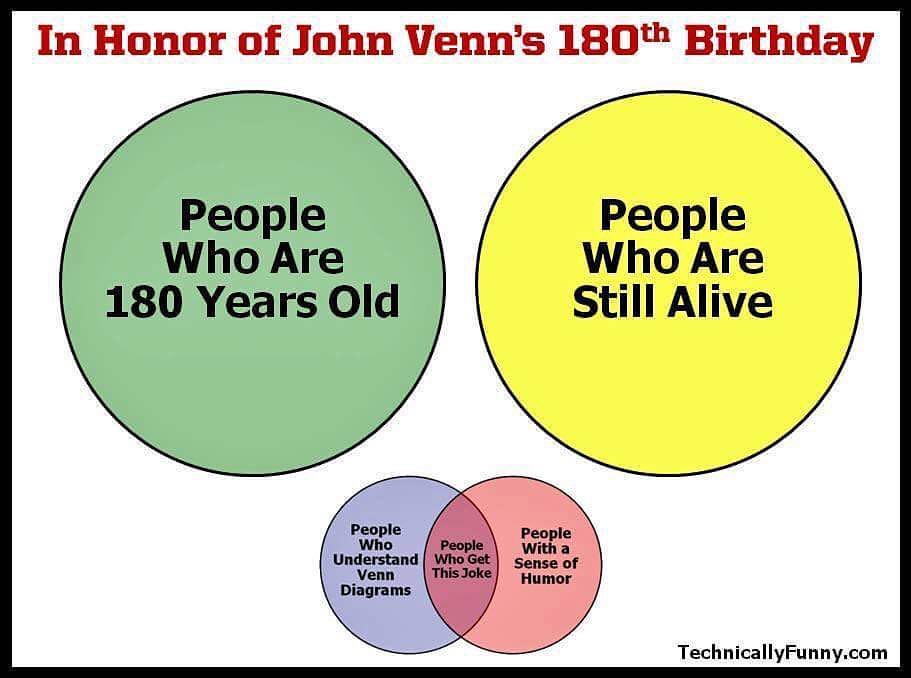

This student submission comes from my former student Amber Northcott. Her topic, from Probability: Venn diagrams.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

There are a few activities you can do with Venn diagrams. One idea is for the first day of class you can put up a big poster with a Venn diagram on it or you can draw one on the board. One circle can be ‘loves math’, while the other is ‘do not like math’. Then of course the center where the two circles intertwine will be the students who love math, but yet don’t like it. When your students come into the room you can have them put their name where it seems fit. This way you can get to better know your students on the topic of math. Another idea is that when you get to a topic, for instance arithmetic and geometric sequences, you can create a giant poster Venn diagram or draw it on the board. Then you can have your students write one thing that either arithmetic has or geometric has or both of them have. Once each student has put up just one thing on the Venn diagram, you can start a class discussion on the Venn diagram. While the discussion goes on you may fix a couple things here and there or even add to it. At the end each student will have their own Venn diagram to fil out, so they can have it in their notes.

How can this topic be used in your students’ future courses in mathematics or science?

Venn diagrams are an easier way to compare and contrast two topics. It can help differentiate between the two topics. For example, how are geometric and arithmetic sequences different? Do they have anything in common? What do they have in common? This helps students identify the topics more thoroughly and helps them get a better understanding about each topic.

How has this topic appeared in the news.

Not too long ago Hillary Clinton posted a Venn diagram about gun control on twitter. In response she was getting mocked and criticized. A short article on thehill.com goes into the mockery by showing pictures of people’s tweets to Hillary Clinton. Some had two circles separate from each other with one stating people who know how to make Venn diagrams and the other one stating Hillary’s graphic design staff. The other article from the Washington Post actually goes through her Venn diagram and fixes errors. These errors include the data in the Venn diagram.

Letting students see this, would definitely cause a discussion. I think we can turn the discussion into whether or not we think the Venn diagram was wrong. By having this discussion, we can learn more about what the students know about Venn diagrams and shed more light on how we can use the Venn diagrams in many different ways for many different topics.

References