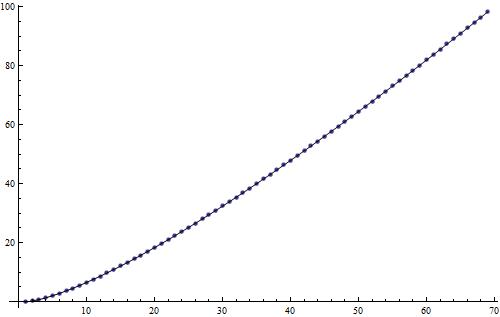

The following graph shows the number of digits in as a function of

.

When I was in school, I stared at this graph for weeks, if not months, trying to figure out an equation that would fit these points. And I never could figure it out.

When I took calculus in college, I distinctly remember getting up the nerve to ask my professor, the great L.Craig Evans (now at UC Berkeley), if he knew how to solve this problem. To my great consternation, he immediately wrote down what I now realize to be the right answer, using Stirling’s approximation:

While I now know that this was the way to go about solving this problem, I didn’t appreciate how this formula could help me at the time. I only saw the on the left-hand side and did not see the immediate connection between this formula and the number of digits in

.

But now I know better.

For starters, the number of base-10 digits in a number is always the next integer greater that

. For example, $\log_{10} 2000 \approx 3.301$, and the next integer larger than

is 4. Unsurprisingly, the number

has 4 digits.

Second, the change of base formula for logarithms gives

Therefore, the number of digits in will be about

The graph below shows just how accurate this approximation really is. The solid curve is the approximation; the dots are the values of . (In other words, this series of dots are only slightly different than the dots above, which have integers as coordinates.) Not bad at all… the error in the approximation is smaller than the size of the dots in this picture.

Part 1

Part 1