Courtesy Math with Bad Drawings: https://wordpress.com/read/post/id/48254001/2942/

Tag: trigonometry

Inverse Functions: Index

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on the different definitions on inverse functions that appear in Precalculus and Calculus.

Square Roots, nth Roots, and Rational Exponents

Part 1: Simplifying

Part 2: The difference between and solving

Part 3: Definition of an inverse function and the horizontal line test

Part 4: Why extraneous solutions may occur when solving algebra problems involving a square root

Part 5: Defining

Part 6: Consequences of the definition of : simplifying

Part 7: Defining if

is odd or even

Part 8: Rational exponents if the denominator of the exponent is odd or even

Arcsine

Part 9: There are infinitely many solutions to

Part 10: Defining arcsine with domain

Part 11: Pedagogical thoughts on teaching arcsine.

Part 12: Solving SSA triangles: impossible case

Part 13: Solving SSA triangles: one way of getting a unique solution

Part 14: Solving SSA triangles: another way of getting a unique solution

Part 15: Solving SSA triangles: continuation of Part 14

Part 16: Solving SSA triangles: ambiguous case of two solutions

Part 17: Summary of rules for solving SSA triangles

Arccosine

Part 18: Definition for arccosine with domain

Part 19: The Law of Cosines and solving SSS triangles

Part 20: Identifying impossible triangles with the Law of Cosines

Part 21: The Law of Cosines provides an unambiguous angle, unlike the Law of Sines

Part 22: Finding the angle between two vectors

Part 23: A proof for why the formula in Part 22 works

Arctangent

Part 18: Definition for arctangent with domain

Part 24: Finding the angle between two lines

Part 25: A proof for why the formula in Part 24 works.

Arcsecant

Part 26: Defining arcsecant using

Part 27: Issues that arise in calculus using the domain

Part 28: More issues that arise in calculus using the domain

Part 29: Defining arcsecant using

Logarithm

Part 30: Logarithms and complex numbers

Mathematical Christmas gifts

Now that Christmas is over, I can safely share the Christmas gifts that I gave to my family this year thanks to Nausicaa Distribution (https://www.etsy.com/shop/NausicaaDistribution):

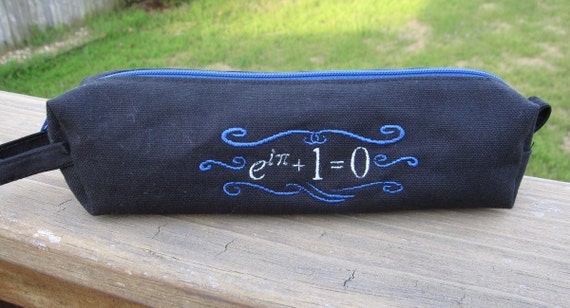

Euler’s equation pencil pouch:

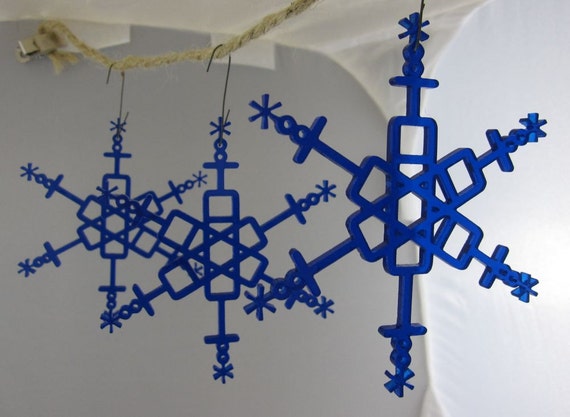

Box-and-whisker snowflakes to hang on our Christmas tree:

And, for me, a wonderfully and subtly punny “Confidence and Power” T-shirt.

Thanks to FiveThirtyEight (see http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-fivethirtyeight-2014-holiday-gift-guide/) for pointing me in this direction.

For the sake of completeness, here are the math-oriented gifts that I received for Christmas:

For the sake of completeness, here are the math-oriented gifts that I received for Christmas:

Engaging students: Computing trigonometric functions

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Nataly Arias. Her topic, from Precalculus: computing trigonometric functions.

How has this topic appeared in pop culture (movies, TV, current music, video games, etc.)?

Trigonometry does not only relate to mathematics, trigonometry is also used in real life. Many people don’t know that trigonometry is involved in video games. In game development, there are many situations where you will need to use trig functions. Video games are full of triangles. For example in order to calculate the direction the player is heading you will form a triangle and use sine, cosine, or tangent to solve. The trig function used depends on the values given. For example if the opposite and adjacent values are given (the xSpeed and ySpeed), the function you will need to calculate the direction of the player is tangent. This is represented by the equation Tan( Dir ) = xSpeed /ySpeed. Again, by applying the inverted function of tan to both sides of the equal sign, we get an equation that will return the player’s direction. In a spaceship game you will need to use trigonometric functions to have one ship shoot a laser in the direction of the other ship, play a warning sound effect if an enemy ship is getting too close, or have one ship start moving in the direction of another ship to chase. Trig is used in several situations in video games some more examples include calculating a new trajectory after a collision between two objects such as billiard balls, rotating a spaceship or other vehicle, properly handling the trajectory of projectiles shot from a rotated weapon, and determining if a collision between two objects is happening.

How has this topic appeared in high culture (art, classical music, theatre, etc.)?

The “unit circle” is a circle with a radius of 1 that is centered at the origin in the Cartesian coordinate system in the Euclidean plane. Because the radius is 1 we can directly measure sine, cosine, and tangent. The unit circle has made parts of mathematics easier and neater. The concepts of the unit circle go far back into the past. Not only do we use and see circles in mathematics we also can see circles in art form. We can also use trigonometric functions to determine the best position to view a painting hanging on an art gallery wall. For example you can determine the angle between a person’s eye and the top and base of the painting when a person is standing 1m away, 2 m away, 3 m away and so on. By comparing your data you can estimate the best position for a person to stand in front of the painting. Also using trig functions and your handy calculator you can develop a formula that describes the relationship between the distance away from the painting and the angle that exists between the person’s eye and the top and bottom of the painting.

How have different cultures throughout time used this topic in their society?

Today the unit circle is used as a helpful tool to help calculate trig functions. Trig functions are taught in trigonometry, pre-calculus and are frequently used in advanced math classes. Many people don’t realize that not only are trig functions learned and used in school but throughout time several cultures have used trig functions in their society. The main application of trigonometry in past cultures was in astronomy. In 1900 BC the Babylonians kept details of stars, the motion of planets, and solar eclipses by using angular distance measured on the celestial sphere. In 1680-1620 BC the Egyptians used ancient forms of trigonometry for building pyramids. The idea of dividing a circle into 360 equal pieces goes back to the sexagesimal counting system of the ancient Sumerians. Early astronomical calculations wedded the sexagesimal system to circles and the rest is history. Today in trigonometry the unit circle has a radius of 1 unlike the Greek, Indian, Arabic, and early Europeans who used a circle of some other convenient radius. In today’s society trigonometry is everywhere. The mathematics used behind trigonometry is the same mathematics that allows us to store sound waves digitally onto a CD. We use it without even knowing it. When we plug something into the wall there is trigonometry involved. The sine and cosine wave are the waves that are running through the electrical circuit known as alternating current.

References

http://www.math.ucdenver.edu/~jloats/Student%20pdfs/40_Trigonometry_Trenkamp.pdf

http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~matc/math5.geometry/unit9/unit9.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trigonometric_functions

http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/ma105/trighist.html

http://www.slideshare.net/mgeis784/building-the-unit-circle

http://www.softlion.nl/download/article/Trigonometry.pdf

http://www.raywenderlich.com/35866/trigonometry-for-game-programming-part-1

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/3946892/trigonometry-and-game-development

Engaging students: Verifying trigonometric identities

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Michelle McKay. Her topic, from Precalculus: verifying trigonometric identities.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Engaging students with trigonometric identities may seem daunting, but I believe the key to success for this unit lies within allowing students to make the discovery of the identities themselves.

For this particular activity, I will focus on some trigonometric identities that can be derived using the Pythagorean Theorem. Before beginning this activity, students must already know about the basic trig functions (sine, cosine, and tangent) along with their corresponding reciprocals (cosecant, secant, and cotangent).

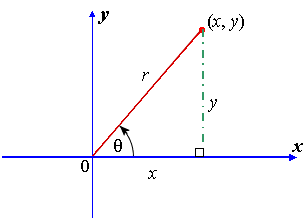

Using this diagram (or a similar one), have students write out the relationship between all sides using the Pythagorean Theorem.

Students should all come to the conclusion of: x2 + y2 = r2.

For higher leveled students, you may want to remind them of the adage SohCahToa, with emphasis on sine and cosine for this next part. You might ask, “How can we rearrange the above equation into something remotely similar to a trigonometric function?”

Ultimately, we want students to divide each side by r2. This will give us:

Again, SohCahToa. Students, perhaps with some leading questions, should see that we can substitute sine and cosine functions into the above equation, giving us the identity:

cos2θ + sin2θ = 1

From this newly derived identity, students can then go on to find tan2θ + 1 = sec2θand then 1 + cot2θ = csc2θ.

How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

For engaging the students and encouraging them to play around with identities, I find the Trigonometric Identities Solver by Symbolab to be a fabulous technological supplement. Students can enter in identities that they may need more help understanding and this website will state whether the identity is true or not, and then provide detailed steps on how to derive the identity.

A rather fun activity that may utilize this site is to challenge the students to come up with their own elaborate trigonometric identity.

Another online tool students can explore is the interactive graph from http://www.intmath.com. In fact, students could also use this right after they derive the identities from the earlier activity. This site does a wonderful job at providing a visual representation of the trigonometric functions’ relationships to one another. It also allows the students to explore the functions using concrete numbers, rather than the general Ө. Although this site only shows the cos2θ + sin2θ = 1identity in action, it would not be difficult for students to plug in the data from this graph to numerically verify the other identities.

What are the contributions of various cultures to this topic?

The beginning of trigonometry began with the intention of keeping track of time and the quickly expanding interest in the study of astronomy. As each civilization inherited old discoveries from their predecessors, they added more to the field of trigonometry to better explain the world around them. The below table is a very brief compilation of some defining moments in trigonometry’s history. It is by no means complete, but was created with the intention to capture the essence of each civilization’s biggest contributions.

| Civilization | People of Interest | Contributions |

| Egyptians |

|

– Earliest ideas of angles.- The Egyptian seked was the cotangent of an angle at the base of a building. |

| Babylonians | – Division of the circle into 360 degrees.- Detailed records of moving celestial bodies (which, when mapped out, resembled a sine or cosine curve).- May have had the first table of secants. | |

| Greek |

|

– Chords.- Trigonometric proofs presented in a geometric way.- First widely recognized trigonometric table: Corresponding values of arcs and chords.- Equivalent of the half-angle formula. |

| Indian |

|

– Sine and cosine series.- Formula for the sine of an acute angle.- Spherical trigonometry.- Defined modern sine, cosine, versine, and inverse sine. |

| Islamic |

|

– – First accurate sine and cosine tables.- – First table for tangent values.- – Discovery of reciprocal functions (secant and cosecant).- – Law of Sines for spherical trigonometry.- – Angle addition in trigonometric functions. |

| Germans | – “Modern trigonometry” was born by defining trigonometry functions as ratios rather than lengths of lines. |

It is interesting to note that while the Chinese were making many advances in other fields of mathematics, there was not a large appreciation for trigonometry until long after they approached the study and other civilizations had made significant contributions.

Sources

- http://www.intmath.com/analytic-trigonometry/1-trigonometric-identities.php

- http://www.intmath.com/analytic-trigonometry/trig-ratios-interactive.php

- http://symbolab.com/solver

- http://www.trigonometry-help.net/history-of-trigonometry.php

- http://nrich.maths.org/6843&part=

- http://www.scribd.com/doc/33216837/The-History-of-Trigonometry-and-of-Trigonometric-Functions-May-Span-Nearly-4

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/605281/trigonometry/12231/History-of-trigonometry

Inverse Functions: Logarithms and Complex Numbers (Part 30)

Ordinarily, there are no great difficulties with logarithms as we’ve seen with the inverse trigonometric functions. That’s because the graph of satisfies the horizontal line test for any

or

. For example,

,

and we don’t have to worry about “other” solutions.

However, this goes out the window if we consider logarithms with complex numbers. Recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. This is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

Over the past few posts, we developed the following theorem for computing in the case that

is a complex number.

Definition. Let be a complex number so that

. Then we define

.

Of course, this looks like what the definition ought to be if one formally applies the Laws of Logarithms to . However, this complex logarithm doesn’t always work the way you’d think it work. For example,

.

This is analogous to another situation when an inverse function is defined using a restricted domain, like

or

.

The Laws of Logarithms also may not work when nonpositive numbers are used. For example,

,

but

.

This material appeared in my previous series concerning calculators and complex numbers: https://meangreenmath.com/2014/07/09/calculators-and-complex-numbers-part-21/

Inverse functions: Arcsine and SSA (Part 17)

In the last few posts, we studied the SSA case of solving for a triangle, when two sides and an non-included angle are given. (Some mathematics instructors happily prefer the angle-side-side acronym to bluntly describe the complications that arise from this possibly ambiguous case. I personally prefer not to use this acronym.)

A note on notation: when solving for the parts of ,

will be the length of the side opposite

,

will be the length of the side opposite

, and

will be the length of the side opposite angle

. Also

will be the measure of

,

will be measure of

, and

will be the measure of

. Modern textbooks tend not to use

,

, and

for these kinds of problems, for which I have only one response:https://meangreenmath.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/philistines.png

Suppose that ,

, and the nonincluded angle

are given, and we are supposed to solve for

,

, and

. As we’ve seen in this series, there are four distinct cases — and handling these cases requires accurately solving equation like

on the interval

.

Case 1. . In this case, there are no solutions. When the Law of Sines is employed and we reach the step

the is greater than 1, which is impossible.

Case 2. . This rarely arises in practice (except by careful writers of textbooks). In this case, there is exactly one solution. When the Law of Sines is employed, we obtain

We conclude that , so that

is a right triangle.

Case 3. . This is the ambiguous case that yields two solutions. The Law of Sines yields

so that there are two possible choices for ,

and

.

Case 4. . This yields one solution. Similar to Case 3, the Law of Sines yields

so that there are two possible choices for ,

and

. However, when the second larger value of

is attempted, we end up with a negative angle for

, which is impossible (unlike Case 3).

Many mathematics students prefer to memorize rules like those listed above. However, I try to encourage my students not to blindly use rules when solving the SSA case, as it’s just too easy to make a mistake in identifying the proper case. Instead, I encourage them to use the Law of Sines and to remember that the equation

Many mathematics students prefer to memorize rules like those listed above. However, I try to encourage my students not to blindly use rules when solving the SSA case, as it’s just too easy to make a mistake in identifying the proper case. Instead, I encourage them to use the Law of Sines and to remember that the equation

has two solutions in as long as $0 < t < 1$:

If they can remember this fact, then students can just follow their noses when applying the Law of Sines, identifying impossible and ambiguous cases when the occasions arise.

Inverse functions: Arcsine and SSA (Part 16)

We’ve seen in this series that blinding using the arcsine function on a calculator is insufficient for finding all solutions of an equation like . In today’s post, I discuss one of the first places that this becomes practically important: solving the ambiguous case of solving a triangle given two sides and an nonincluded angle.

A note on notation: when solving for the parts of ,

will be the length of the side opposite

,

will be the length of the side opposite

, and

will be the length of the side opposite angle

. Also

will be the measure of

,

will be measure of

, and

will be the measure of

. Modern textbooks tend not to use

,

, and

for these kinds of problems, for which I have only one response:

Why does an SSA triangle produce an ambiguous case (unlike the SAS, SSS, or ASA cases)? Here’s a possible problem that has two different solutions:

Solve

if

,

, and

.

A student new to the Law of Sines might naively start solving the problem by drawing something like this:

Of course, that’s an inaccurate picture that isn’t drawn to scale. A more accurate picture would look like this:

This time, the red circle intersects the dashed black line at two different points. So there will be two different solutions for this case. In other words, the phrasing of the question is somewhat deceptive. Usually when the question asks, “Solve the triangle…”, it’s presumed that there is only one solution. In this case, however, there are two different solutions.

This time, the red circle intersects the dashed black line at two different points. So there will be two different solutions for this case. In other words, the phrasing of the question is somewhat deceptive. Usually when the question asks, “Solve the triangle…”, it’s presumed that there is only one solution. In this case, however, there are two different solutions.

These two different solutions appear when using the Law of Sines:

At this point, the natural inclination of a student is to pop out the calculator and find .

This is incorrect logic that, as discussed extensively in earlier in this series of posts, there are two angles between and

with a sine of

:

,

or, in degrees,

So we have two different cases to check. Unlike the previous posts in this series, it’s really, really important that we list both of these cases.

Case 1: . We begin by solving for

:

Then we can use the Law of Sines to find . In this case, it’s best to use the pair

instead of

since the values of

and

are both known exactly.

This triangle with ,

, and

corresponds to the bigger of the two triangles in the above picture, or the rightmost of the two places where the dotted circle intersects the black dotted line.

Case 2: . We again begin by solving for

:

Unlike yesterday’s example, this is possible. So we have to continue the calculation to find :

This second triangle with ,

, and

corresponds to the thinner of the two triangles in the above picture, or the leftmost of the two places where the dotted circle intersects the black dotted line.

Inverse functions: Arcsine and SSA (Part 15)

We’ve seen in this series that blinding using the arcsine function on a calculator is insufficient for finding all solutions of an equation like . In today’s post, I discuss one of the first places that this becomes practically important: solving the ambiguous case of solving a triangle given two sides and an nonincluded angle.

A note on notation: when solving for the parts of ,

will be the length of the side opposite

,

will be the length of the side opposite

, and

will be the length of the side opposite angle

. Also

will be the measure of

,

will be measure of

, and

will be the measure of

. Modern textbooks tend not to use

,

, and

for these kinds of problems, for which I have only one response:

Why does an SSA triangle produce an ambiguous case (unlike the SAS, SSS, or ASA cases)? Here’s a possible problem that has exactly one solution:

Solve

if

,

, and

.

A student new to the Law of Sines might naively start solving the problem by drawing something like this:

Of course, that’s an inaccurate picture that isn’t drawn to scale. A more accurate picture would look like this:

Notice that the red circle intersects the dashed black line at exactly one point. Therefore, we know that there will be exactly one solution for this case. We also note that the circle would have intersected the black dashed line had the dashed line been extended to the left. This will become algebraically clear in the solution below.

Of course, students should not be expected to make a picture this accurately when doing homework. Fortunately, this impossibility naturally falls out of the equation when using the Law of Sines:

At this point, the natural inclination of a student is to pop out the calculator and find .

This is incorrect logic that, as discussed extensively in yesterday’s post, there are two angles between and

with a sine of

:

,

or, in degrees,

So we have two different cases to check.

Case 1: . We begin by solving for

:

Then we can use the Law of Sines (or, in this case, the Pythagorean Theorem), to find . In this case, it’s best to use the pair

instead of

since the values of

and

are both known exactly.

Case 2: . We again begin by solving for

:

Oops. That’s clearly impossible. So there is only one possible triangle, and the missing pieces are ,

, and

. Judging from the above (correctly drawn) picture, these numbers certainly look plausible.

It turns out that Case 2 will always fail in SSA will always fail as long as the side opposite the given angle is longer than the other given side (in this case, ). However, I prefer that my students not memorize this rule. Instead, I’d prefer that they list the two possible values of

and then run through the logical consequences, stopping when an impossibility is reached. As we’ll see in tomorrow’s post, it’s perfectly possible for Case 2 to produce a second valid solution with the proper choice for the length of the side opposite the given angle.

Inverse functions: Arcsine and SSA (Part 14)

We’ve seen in this series that blinding using the arcsine function on a calculator is insufficient for finding all solutions of an equation like . In today’s post, I discuss one of the first places that this becomes practically important: solving the ambiguous case of solving a triangle given two sides and an nonincluded angle.

A note on notation: when solving for the parts of ,

will be the length of the side opposite

,

will be the length of the side opposite

, and

will be the length of the side opposite angle

. Also

will be the measure of

,

will be measure of

, and

will be the measure of

. Modern textbooks tend not to use

,

, and

for these kinds of problems, for which I have only one response:

Why does an SSA triangle produce an ambiguous case (unlike the SAS, SSS, or ASA cases)? Here’s a possible problem that has exactly one solution:

Solve

if

,

, and

.

A student new to the Law of Sines might naively start solving the problem by drawing something like this:

Of course, that’s an inaccurate picture that isn’t drawn to scale. A more accurate picture would look like this:

Notice that the red circle intersects the dashed black line at exactly one point. Therefore, we know that there will be exactly one solution for this case. We also note that the circle would have intersected the black dashed line had the dashed line been extended to the left. This will become algebraically clear in the solution below.

Of course, students should not be expected to make a picture this accurately when doing homework. Fortunately, this impossibility naturally falls out of the equation when using the Law of Sines:

At this point, the natural inclination of a student is to pop out the calculator and find .

This is incorrect logic that, as we’ll see tomorrow, nevertheless leads to the correct conclusion. This is incorrect logic because there are two angles between and

with a sine of

. There is one solution in the first quadrant (the unique answer specified by arcsine), and there is another answer in the second quadrant — which is between

and

and hence not a permissible value of arcsine. Let me demonstrate this in three different ways.

First, let’s look at the graph of (where, for convenience, the units of the

axis are in degrees). This graph intersects the line

in two different places between

and

. This does not violate the way that arcsine was defined — arcsine was defined using the restricted domain

, or

in degrees.

Second, let’s look at drawing angles in standard position. The angle in the second quadrant is clearly the reflection of the angle in the first quadrant through the axis.

Third, let’s use a trigonometric identity to calculate :

Fourth, and perhaps most convincingly for modern students (to my great frustration), let’s use a calculator:

All this to say, blinding computing uses incorrect logic when solving this problem.

Tomorrow, we’ll examine what happens when we try to solve the triangle using these two different solutions for .