We now turn to a little-taught and perhaps controversial inverse function: arcsecant. As we’ve seen throughout this series, the domain of this inverse function must be chosen so that the graph of  satisfies the horizontal line test. It turns out that the choice of domain has surprising consequences that are almost unforeseeable using only the tools of Precalculus.

satisfies the horizontal line test. It turns out that the choice of domain has surprising consequences that are almost unforeseeable using only the tools of Precalculus.

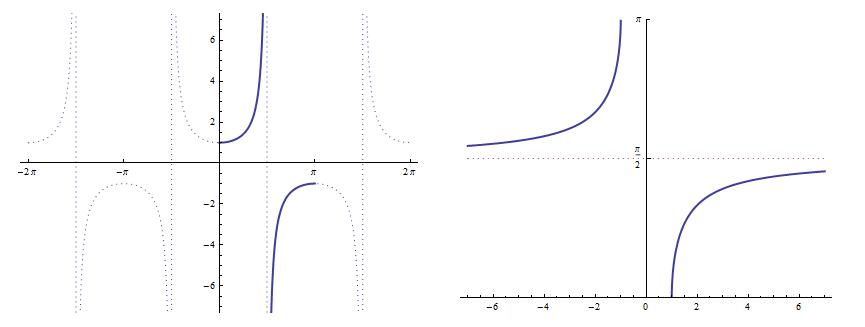

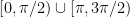

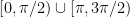

The standard definition of  uses the interval

uses the interval ![[0,\pi]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C%5Cpi%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) — or, more precisely,

— or, more precisely, ![[0,\pi/2) \cup (\pi/2, \pi]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C%5Cpi%2F2%29+%5Ccup+%28%5Cpi%2F2%2C+%5Cpi%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) to avoid the vertical asymptote at

to avoid the vertical asymptote at  — in order to approximately match the range of

— in order to approximately match the range of  . However, when I was a student, I distinctly remember that my textbook chose

. However, when I was a student, I distinctly remember that my textbook chose  as the range for

as the range for  .

.

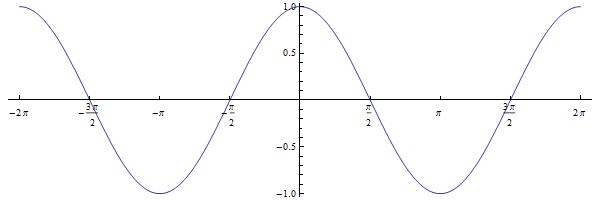

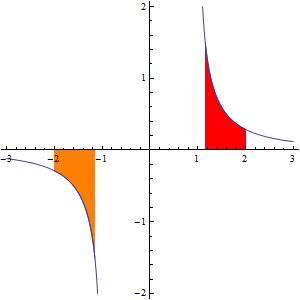

I believe that this definition has fallen out of favor today. However, for the purpose of today’s post, let’s just run with this definition and see what happens. This portion of the graph of  is perhaps unorthodox, but it satisfies the horizontal line test so that the inverse function can be defined.

is perhaps unorthodox, but it satisfies the horizontal line test so that the inverse function can be defined.

Let’s fast-forward a couple of semesters and use implicit differentiation (see also https://meangreenmath.com/2014/08/08/different-definitions-of-logarithm-part-8/ for how this same logic is used for other inverse functions) to find the derivative of  :

:

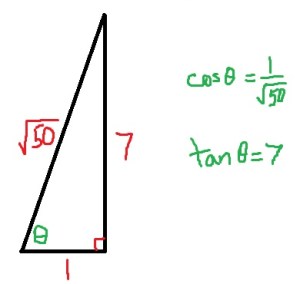

At this point, the object is to convert the left-hand side to something involving only  . Clearly, we can replace

. Clearly, we can replace  with

with  . As it turns out, the replacement of

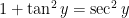

. As it turns out, the replacement of  is a lot simpler than we saw in yesterday’s post. Once again, we begin with one of the Pythagorean identities:

is a lot simpler than we saw in yesterday’s post. Once again, we begin with one of the Pythagorean identities:

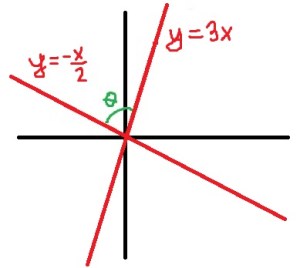

So which is it, the positive answer or the negative answer? In yesterday’s post, the answer depended on whether  was positive or negative. However, with the current definition of

was positive or negative. However, with the current definition of  , we know for certain that the answer is the positive one! How can we be certain? The angle

, we know for certain that the answer is the positive one! How can we be certain? The angle  must lie in either the interval

must lie in either the interval  or else the interval

or else the interval  . In either interval,

. In either interval,  is positive. So, using this definition of

is positive. So, using this definition of  , we can simply say that

, we can simply say that

,

,

and we don’t have to worry about  that appeared in yesterday’s post.

that appeared in yesterday’s post.

Turning to integration, we now have the simple formula

Turning to integration, we now have the simple formula

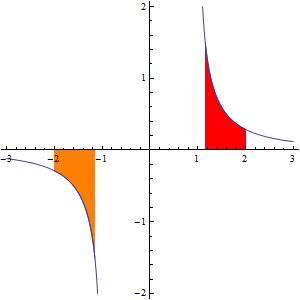

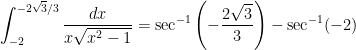

that works whether  is positive or negative. For example, the orange area can now be calculated correctly:

is positive or negative. For example, the orange area can now be calculated correctly:

So, unlike yesterday’s post, this definition of  produces a simple integration formula.

produces a simple integration formula.

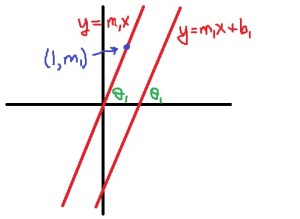

So why isn’t this the standard definition for  ? I’m afraid the answer is simple: with this definition, the equation

? I’m afraid the answer is simple: with this definition, the equation

is no longer correct if  . Indeed, I distinctly remember thinking, back when I was a student taking trigonometry, that the definition of

. Indeed, I distinctly remember thinking, back when I was a student taking trigonometry, that the definition of  seemed really odd, and it seemed to me that it would be better if it matched that of

seemed really odd, and it seemed to me that it would be better if it matched that of  . Of course, at that time in my mathematical development, it would have been almost hopeless to explain that the range

. Of course, at that time in my mathematical development, it would have been almost hopeless to explain that the range  had been chosen to simplify certain integrals from calculus.

had been chosen to simplify certain integrals from calculus.

So I suppose that The Powers That Be have decided that it’s more important for this identity to hold than to have a simple integration formula for

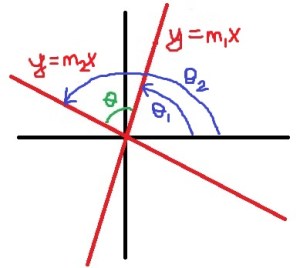

So far in this series, I’ve shown that

So far in this series, I’ve shown that, so that

. Also, the endpoints change from

to

, so that