Source: https://xkcd.com/3102/

Source: https://xkcd.com/3102/

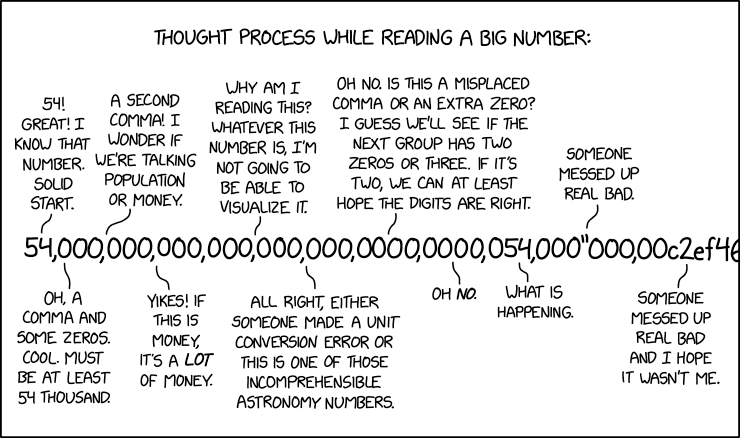

I recently read the article Pipe Dreams about treating wastewater. I’m not an engineer and make no claims of expertise about the accuracy of the article. What did catch my attention, as a mathematician, is how the author chose to express small proportions. For example, the opening sentence:

Wastewater is 99.9 percent water, but boy, that last little bit.

Later in the article:

Orange County’s is an example of indirect potable reuse, where wastewater is cleansed to 99.9999999999 percent free of pathogens before it goes to an environmental buffer like a reservoir or an aquifer for further natural filtering and then to homes.

And later:

After treating the water to even higher standards—demonstrating a 99.999999999999999999 percent removal rate of viruses and similarly high removal rates of protozoa—they may send the cleansed water directly into the water distribution system.

I was struck about the psychology of communicating all those consecutive 9s when expressing these proportions. For example, if the proportion of impurities instead of the proportion of water was given, the previous sentences could be rewritten as:

Only one part per thousand of wastewater is impurities.

Orange County’s is an example of indirect potable reuse, where impurities are reduced to one part per trillion before it goes to an environmental buffer like a reservoir or an aquifer for further natural filtering and then to homes.

After treating the water to even higher standards, reducing impurities to one part per 100 million trillion, they may send the cleansed water directly into the water distribution system.

Of these two different ways of expressing the same information, it seems to me that the author’s original prose is perhaps most psychologically comforting. “One part per trillion” seems a little abstract, as most people don’t have an intuitive notion of just how big a trillion is. The phrase “99.9999999999 percent,” on the other hand, seems at first reading to be ridiculously close to 100 percent (which, of course, it is).

For the last couple years, one of my favorite sources of entertainment has been the wonderful world of YouTube Golf. Intending no disrespect to any other content creators, my favorite channels are the ones by Grant Horvat, the Bryan Bros (not to be confused with the twin tennis duo), Peter Finch, Bryson DeChambeau (of course), and Golf Girl Games (all of them absolutely, positively should have been in the Internet Invitational… but that’s another story for another day).

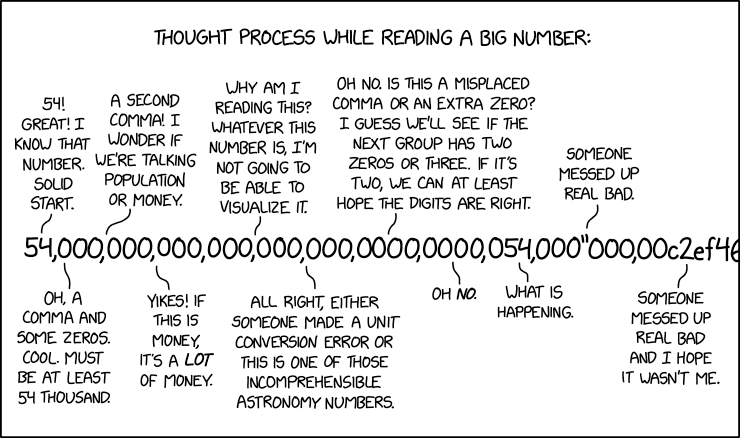

In a recent Bryan Bros video, my two interests collided. To make a long story short, a golf simulator projected that a tee shot on a par-3 ended 8 feet, 12 inches from the cup.

Co-host Wesley Bryan, to his great credit, immediately saw the computer glitch — this is an unusual way of saying the tee shot ended 9 feet from the cup. Hilarity ensued as the golfers held a stream-of-consciousness debate on the merits of metric and Imperial units. The video is below: the fun begins at the 21:41 mark and ends around 25:30.

As discussed earlier in this blog, here’s one of my favorite mathematical magic tricks. The trick works best when my audience has access to a calculator (including the calculator on a phone). The patter:

Write down any five-digit number you want. Just make sure that the same digit repeated (not something like 88,888).

(pause)

Now scramble the digits of your number, and write down the new number. Just be sure that any repeated digits appear the same number of times. (For example, if your first number was 14,232, your second number could be 24,231 or 13,422.)

(pause)

Is everyone done? Now subtract the smaller of the two numbers from the bigger, and write down the difference. Use a calculator if you wish.

(pause)

Has everyone written down the difference. Good. Now, pick any nonzero digit in the difference, and scratch it out.

(pause)

(I point to someone.) Which numbers did you not scratch out?

The audience member will say something like, “8, 2, 9, and 6.” To which I’ll reply in three seconds or less, “The number you scratched out was a 2.”

Then I’ll turn to someone else and ask which numbers were not scratched out. She’ll say something like, “3, 2, 0, and 7.” I’ll answer, “You scratched out a 6.”

As discussed in a previous post, the difference found by the audience member must be a multiple of 9. Since the sum of the digits of a multiple of 9 must also be a multiple of 9, the magician can quickly figure out the missing digit. In the previous example, . Since the next multiple of 9 after 12 is 18, the magician knows that the missing digit is

.

To speed things up (and to reduce the possibility of a mental arithmetic mistake), the magician doesn’t actually have to add up all of the digits. If the audience member gives a digit of either 0 or 9, then the magician can ignore that digit for purposes of the trick. Likewise, if the magician notices that some subset of the given digits add up to 9, then those digits can be effectively ignored. In the current example, the magician could ignore the 0 and also the 2 and 7 (since ). That leaves only the 3, and clearly one needs to add 6 to 3 to get the next multiple of 9.

I was a little curious about how often this happens — how often the magician can get away with these shortcuts to find the missing digits. So I did some programming in Mathematica. Here’s what I found. If the audience starts with a 5-digit number, so that the difference must be some multiple of 9 between 9 and 99,999:

I’ve put on my mathematical wish-list some kind of theorem about this splitting of digits of multiples of 9s.

Source: https://xkcd.com/3138/

Happy Fourth of July.

I’m a sucker for G-rated ways of using humor to engage students with concepts in the mathematical curriculum. I never thought that Saturday Night Live would provide a wonderful source of material for this effort.

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collecting a series of posts into one single post. The links below show the mathematical magic show that I’ll perform from time to time.

Part 1: Introduction.

Part 2a, Part 2b, and Part 2c: The 1089 trick.

Part 3a, Part 3b, and Part 3c: A geometric magic trick.

Part 4a: Part 4b, Part 4c, and Part 4d: A trick using binary numbers.

Part 5a, Part 5b, Part 5c, and Part 5d: A trick using the rule for checking if a number is a multiple of 9.

Part 7: The Fitch-Cheney card trick, which is perhaps the slickest mathematical card trick ever devised.

Part 8a, Part 8b, and Part 8c: A trick using Pascal’s triangle.

Part 9: Mentally computing given

if

.

Part 10: A mathematical optical illusion.

Part 11: The 27-card trick, which requires representing numbers in base 3.

Part 6: The Grand Finale.

And, for the sake of completeness, here’s a picture of me just before I performed an abbreviated version of this show for UNT’s Preview Day for high school students thinking about enrolling at my university.

A couple years ago, I learned the 27-card trick, which is probably the most popular trick in my current repertoire. In this first video, Matt Parker performs this trick as well as the 49-card trick.

Here’s a quick explanation from the American Mathematical Society for how the magician performs this trick. In short, the magician needs to do some mental arithmetic quickly.

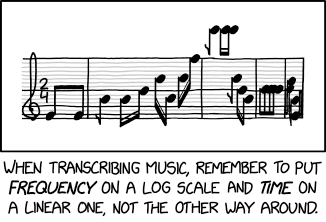

The 27 card trick is based on the ternary number system, sometimes called the base 3 system.

Suppose the volunteer chooses a card and also chooses the number 18. You want to make her chosen card move to the 18th position in the deck, which means you need 17 cards above it. You first need to express 17 in base 3, writing it as a three digit number. For the procedure used in this trick, it’s also handy to write the digits in backward order: 1s digit first, 3s digit second, and 9s digit last. In this backward base 3 notation 17 becomes 221, since 17 = 2×30 + 2×31 + 1×32.

With the understanding that 2 = bottom, 1 = middle, and 0 = top, the number 17 becomes “bottom-bottom-middle.”

Now deal the cards into three piles. The subject identifies the pile containing her card. That pile should be placed at the position indicated by the 1s digit, which is 2, or bottom. After picking up the three piles with the pile containing the chosen card on the bottom, deal the cards a second time into three piles. This time place the pile containing the chosen card in the position indicated by the 3s digit, which is also 2, or bottom. Finally, after placing the pile containing the subject’s card on the bottom, deal the cards into three piles for a third time. When picking up the piles, this time place the pile containing her card in the position indicated by the 9s digit, which is 1, or middle. Deal out 17 cards. The 18th will be her card.

Making a schematic picture of the deck, like Matt does in his second video [below], should convince you that this procedure does precisely what is claimed. But there is no substitute for actually doing it—take 27 cards and try it!

Of course this procedure will work regardless of which position the subject chooses, for her choice is always a number between 1 and 27. This means you need between 0 and 26 cards on top of it, and in base 3 we have 0 = 000 (top-top-top) and 26 = 222 (bottom-bottom-bottom). Every possible position that the subject can choose corresponds to a unique base 3 representation.

In general, if you deal a pack of nk cards into n piles, have the subject identify the pile that contains her card, and repeat this procedure k times, you can place her card at any desired position in the deck. The idea is the same: Subtract one from the desired position number, and convert the result to base n as a k digit number. The ones digit of this number tells you where to place the packet containing her card after the first deal (n – 1 = bottom, 0 = top), and the procedure continues for the remaining deals.

In Mathematics, Magic and Mystery (Dover, 1956), Martin Gardner discusses the long history and many variations of this effect. See Chapter 3, “From Gergonne to Gargantua.”

In this Numberphile video, Matt Parker explains why the trick works.