Source: https://xkcd.com/2768

See also my series on the number e.

In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

One technique that will be necessary for this confirmation is the method of successive approximations. This will be needed in the context of a differential equation; however, we can illustrate the concept by finding the roots of a polynomial. Consider the quadratic equation

.

(Naturally, we can solve for using the quadratic formula; more on that later.) To apply the method of successive approximation, we will rewrite this so that

appears on the left side and some function of

appears on the right side. I will choose

, or

.

Here’s the idea of the method of successive approximations to obtain a recursively defined sequence that (hopefully) convergence to a solution of this equation:

For example, suppose that we choose . Then

This sequence can be computed by entering into a calculator, then entering

, and then repeatedly hitting the

button.

We see that the sequence appears to be converging to something, and that something is a root of the equation , which we now find via the quadratic formula:

.

So it looks like the above sequence is converging to the positive root .

(Parenthetically, you might notice that the Fibonacci sequence appears in the numerators and denominators of this sequence. As you might guess, that’s not a coincidence.)

Like most numerical techniques, this method doesn’t always work like we think it would. Another solution is the negative root . Unfortunately, if we start with a guess near this root, like

, the sequence unexpectedly diverges from

but eventually converges to the positive root

:

I should note that the method of successive approximations generally converges at a slower pace than Newton’s method. However, this method will be good enough when we use it to predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit.

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collecting a series of posts into one single post. The links below show my series on numerical integration.

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Identifying the highest points of the strings

Part 3: These nine points lie on a parabola: Method #1

Part 4: These nine points lie on a parabola: Method #2

Part 5: These nine points lie on a parabola: Method #3

Part 6: Proof that all of the highest points lie on a parabola without calculus, Part 1

Part 7: Proof that all of the highest points lie on a parabola without calculus, Part 2

Part 8: Proof that all of the highest points lie on a parabola with calculus

Part 9: Proof that the strings are indeed tangent to the parabola, with calculus

Part 10: Conclusion

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on computing square roots and logarithms without a calculator (with the latest post added).

Part 1: Method #1: Trial and error.

Part 2: Method #2: An algorithm comparable to long division.

Part 3: Method #3: Introduction to logarithmic tables.

Part 4: Finding antilogarithms with a table.

Part 5: Pedagogical and historical thoughts on log tables.

Part 6: Computation of square roots using a log table.

Part 7: Method #4: Slide rules

Part 8: Method #5: By hand, using a couple of known logarithms base 10, the change of base formula, and the Taylor approximation .

Part 9: An in-class activity for getting students comfortable with logarithms when seen for the first time.

Part 10: Method #6: Mentally… anecdotes from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman and me.

Part 11: Method #7: Newton’s Method.

Part 12: Method #8: The formula

Source: https://xkcd.com/2711/

Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. In this series of posts, I’d wanted to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas for algebra students. After all, most mathematical studies of string art curves — formally known as “envelopes” — rely on differential equations or at least limits and calculus.

However, string art is simple enough for a young child to construct, and so this study was inspired by the quest of explaining this phenomenon using only simple mathematical tools.

The article linked above has further thoughts on this problem, including a calculus-free way of deriving the reflective property of parabolas. However, I think the article pretty much has all of my thoughts on this matter, and so I don’t think I need to elaborate upon them here.

This series of posts is dedicated to an inspired and inspiring Algebra I student who wanted to understand string art curves using tools that she could understand… even though she progressed much further into the mathematics curriculum by the time my article was published and this series of posts appeared on my blog.

Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. While all the necessary mathematics is in the article, I think the article is somewhat lacking on how to sell the idea to students. So, in this series of posts, I’d like to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas.

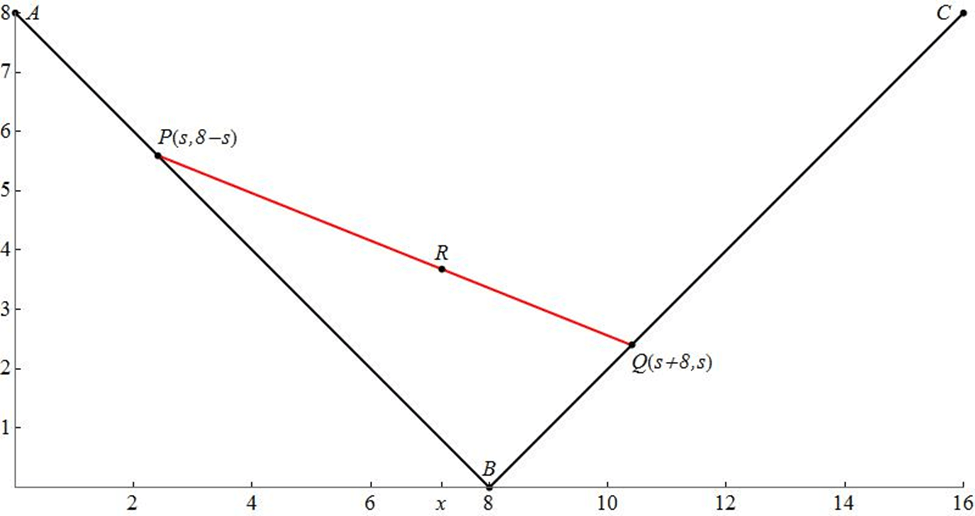

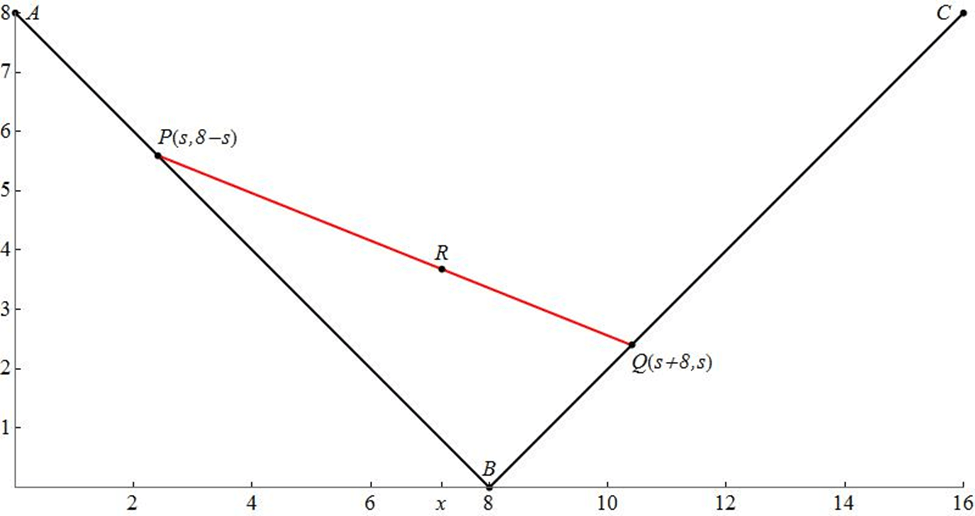

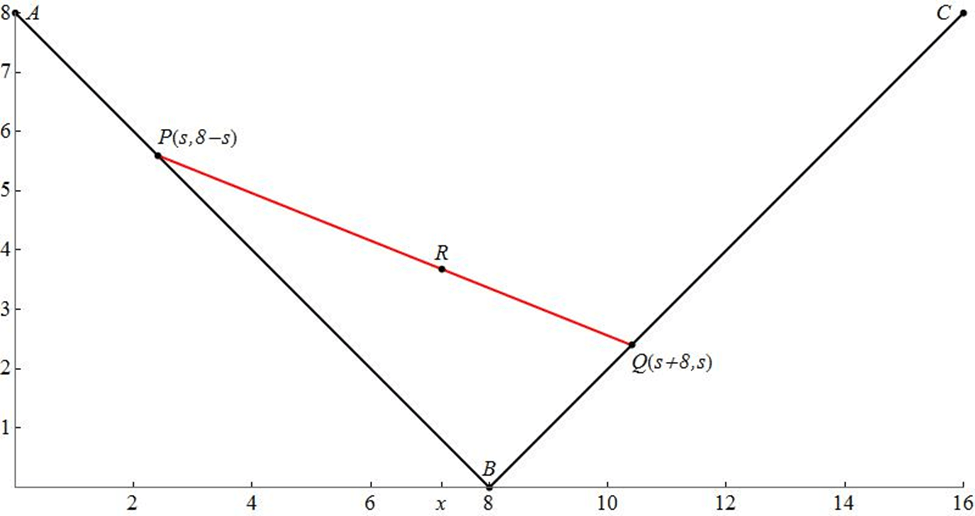

We have shown in the last couple of posts that if the three points that generate the Our explorations of string art led us to consider an arbitrary string depicted below. For brevity, this string will be called “string

,” matching the (possibly non-integer)

-coordinate of its left endpoint

. Since

is

units to the right of

, the right endpoint

must correspondingly be

units to the right of

. Therefore, the

-coordinate of

is

.

Previously, we established that the equation for string is

.

We also obtained a bonus result that we obtained using only algebra: string is tangent to the parabola

, which is traced by the strings, when

. Of course, tangent lines are usually obtained using calculus, and so calculus should be able to confirm this result. The derivative of this function is

,

so that the slope of the tangent line when is

. We observe that this matches the slope of line segment

in the above picture:

slope .

Therefore, to show that is the tangent line, it suffices to show that either

or

is on the tangent line.

At , the

coordinate of where the tangent line intersects the curve is

.

Using the point-slope formula for a line, the equation of the tangent line is thus

.

We now check to see if is on the tangent line. Substituting

, we find

Therefore, the point is on the tangent line, thus confirming that

is on the tangent line and that

is the tangent line.

Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. While all the necessary mathematics is in the article, I think the article is somewhat lacking on how to sell the idea to students. So, in this series of posts, I’d like to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas.

We have shown in the last couple of posts that if the three points that generate the Our explorations of string art led us to consider an arbitrary string depicted below. For brevity, this string will be called “string

,” matching the (possibly non-integer)

-coordinate of its left endpoint

. Since

is

units to the right of

, the right endpoint

must correspondingly be

units to the right of

. Therefore, the

-coordinate of

is

.

Previously, we established that the equation for string is

.

Finding the curve traced by the strings is a two-step process:

Previously, we showed using only algebra that the optimal value of is

, corresponding to an optimal value of

of

.

For a student who knows calculus, the optimal value of can be found by instead solving the equation

(or, more accurately,

):

,

matching the result that we found by using only algebra.

Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. While all the necessary mathematics is in the article, I think the article is somewhat lacking on how to sell the idea to students. So, in this series of posts, I’d like to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas.

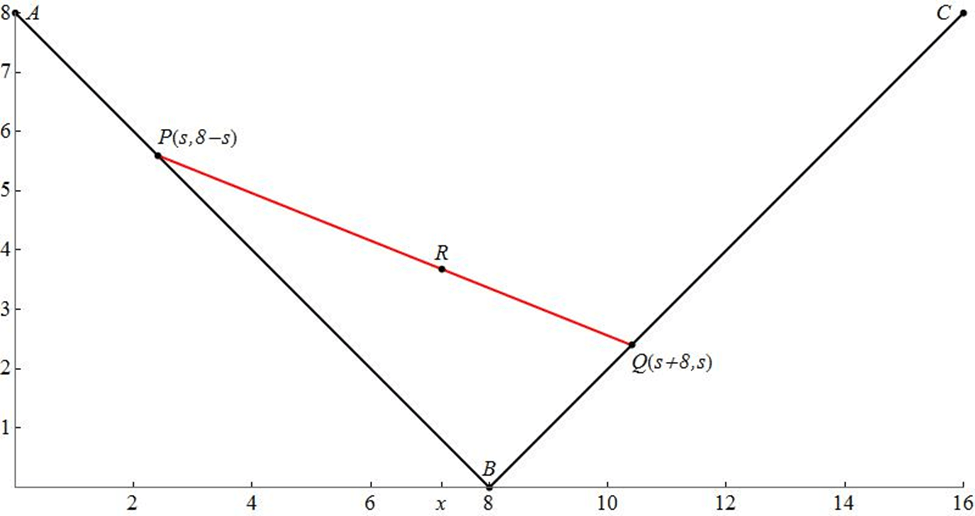

Our explorations of string art led us to consider an arbitrary string depicted below. For brevity, this string will be called “string

,” matching the (possibly non-integer)

-coordinate of its left endpoint

. Since

is

units to the right of

, the right endpoint

must correspondingly be

units to the right of

. Therefore, the

-coordinate of

is

.

In the previous post, we established that the equation for string is

This has the appearance of a quadratic equation, but it’s actually a linear equation in for a fixed value of

. For example, if s = 5, we find that the equation of string 5 is

,

matching the equation of the blue string we found in a previous post in this series.

To prove that the strings trace a parabola, we now determine which string maximizes the value of

for a given value of

. Algebra students can determine this maximum by recalling that a quadratic function

is maximized (for negative

) when

. Therefore, the string with largest

-coordinate for a given value of

is

.

For example, if , then string

has the largest

-coordinate, matching our previous observations.

To complete the proof that the strings above trace a parabola, we substitute into

to find the value of this largest

coordinate:

,

matching the result that we found earlier in this series.

There’s also a bonus result. We further note that, for every , there is only one string

that intersects the parabola

. Since each

is associated with a unique string

and vice versa, we conclude that each string intersects the parabola at exactly one point. In other words, string

is tangent to the parabola

when

.

We note that all of the above calculations were entirely elementary, in the sense that calculus was not used and that only techniques from algebra were employed. That said, the word “elementary” in mathematics can be a bit loaded — this means that it is based on simple ideas that are perhaps used in a profound and surprising way. Perhaps my favorite quote along these lines was this understated gem from the book Three Pearls of Number Theory after the conclusion of a very complicated multi-page proof in Chapter 1:

You see how complicated an entirely elementary construction can sometimes be. And yet this is not an extreme case; in the next chapter you will encounter just as elementary a construction which is considerably more complicated.

In the next post, we take a second look at this derivation using techniques from calculus.

Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. While all the necessary mathematics is in the article, I think the article is somewhat lacking on how to sell the idea to students. So, in this series of posts, I’d like to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas.

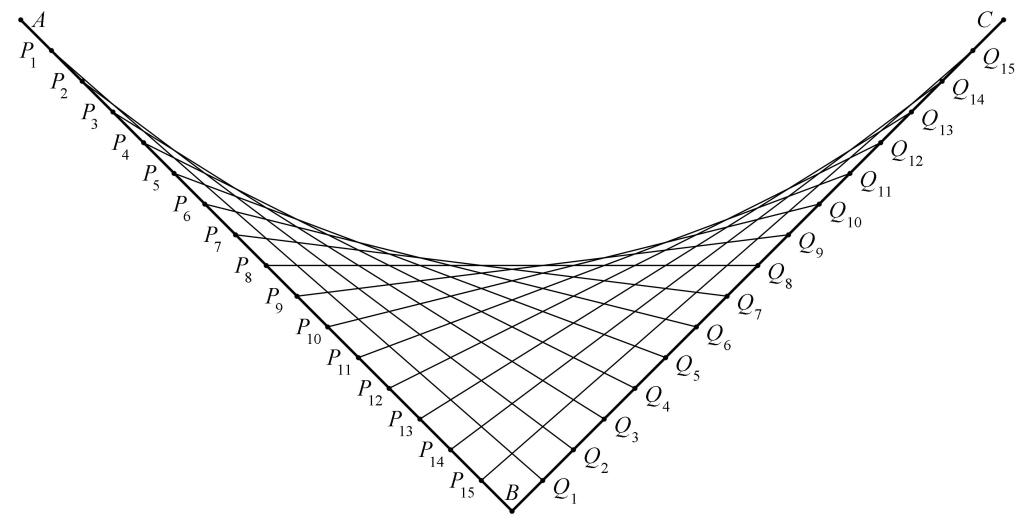

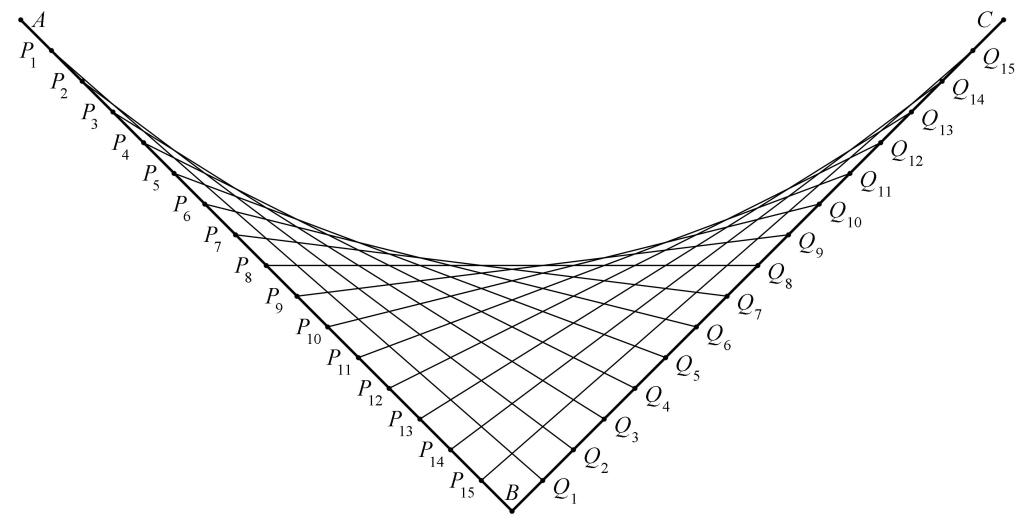

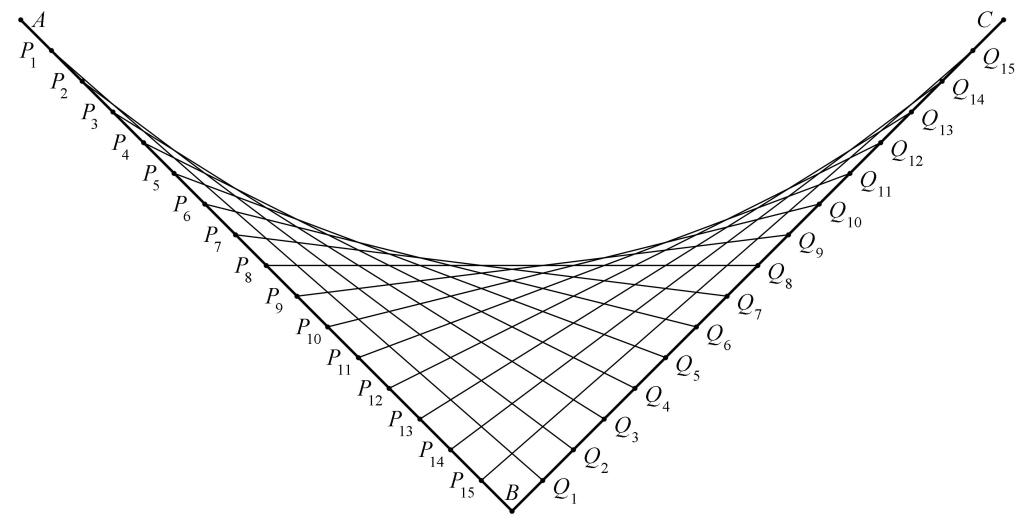

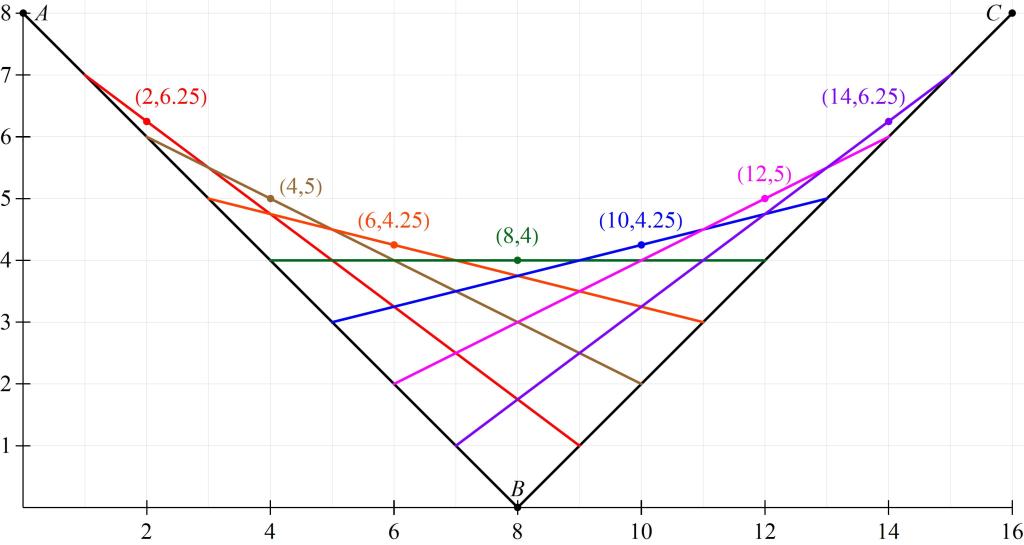

As discussed previous posts, we begin our explorations with string art connecting evenly spaced points on line segments and

with endpoints

,

, and

. We will call these colored line segments “strings.” We then found the string with the largest

coordinate at

, resulting in the following picture:

In previous posts, we discussed three different ways of establishing that the colored points lie on the parabola .

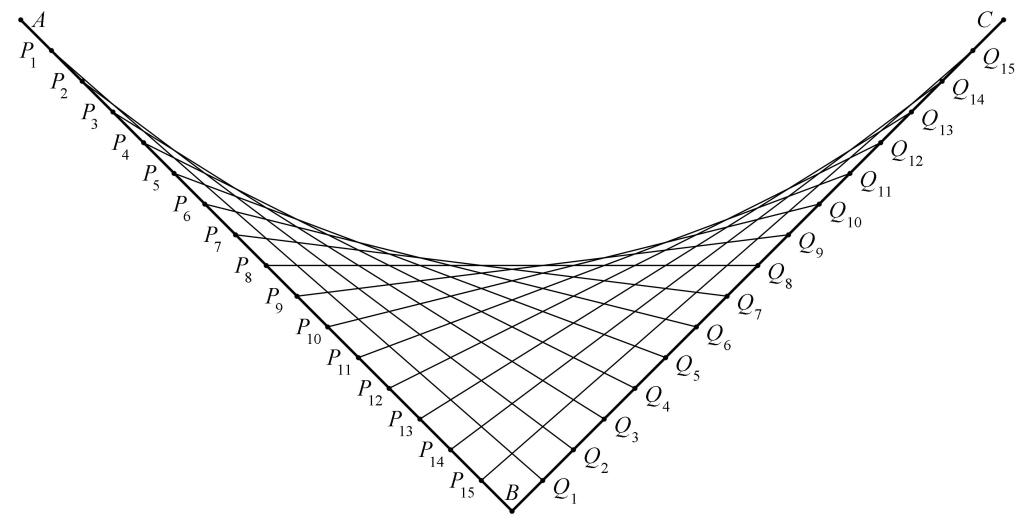

Unfortunately, checking that a statement is true for a few points (in our case, ) does not constitute a complete proof for all points. Furthermore, it’s conceivable that “fuller” string art with additional strings, like the picture below, may identify a new string with a higher

coordinate than a colored point.

To prove that the string art indeed traces a parabola, we study an arbitrary string depicted below. For brevity, this string will be called “string

,” matching the (possibly non-integer)

-coordinate of its left endpoint

. Since

is

units to the right of

, the right endpoint

must correspondingly be

units to the right of

. Therefore, the

-coordinate of

is

.

Since the equations of and

are

and

, respectively, the

coordinates of

and

are

and

, respectively. For example, if

, the coordinates of

are

and the coordinates of

are

, matching the endpoints of the blue string in the first figure.

We now use standard algebraic techniques to find the equation of string . Its slope is

.

The coordinates of either or

can now be used to find the equation of string

via the point-slope formula. As it turns out, the coordinates of

are simpler to use:

to finally arrive at the equation of string :

This has the appearance of a quadratic equation, but it’s actually a linear equation in for a fixed value of

. For example, if s = 5, we find that the equation of string 5 is

,

matching the equation of the blue string we found in a previous post in this series.

We are now almost in position to prove that the string art traces a parabola. We demonstrate this in the next post.