As discussed earlier in this blog, here’s one of my favorite mathematical magic tricks. The trick works best when my audience has access to a calculator (including the calculator on a phone). The patter:

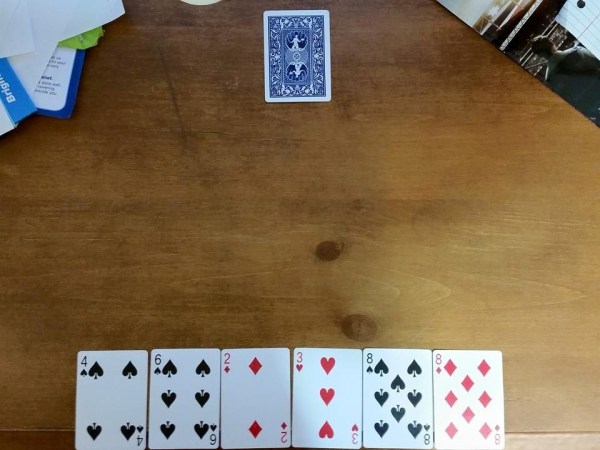

Write down any five-digit number you want. Just make sure that the same digit repeated (not something like 88,888).

(pause)

Now scramble the digits of your number, and write down the new number. Just be sure that any repeated digits appear the same number of times. (For example, if your first number was 14,232, your second number could be 24,231 or 13,422.)

(pause)

Is everyone done? Now subtract the smaller of the two numbers from the bigger, and write down the difference. Use a calculator if you wish.

(pause)

Has everyone written down the difference. Good. Now, pick any nonzero digit in the difference, and scratch it out.

(pause)

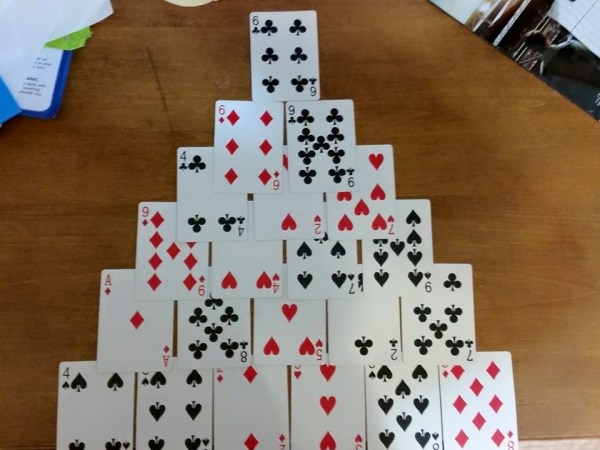

(I point to someone.) Which numbers did you not scratch out?

The audience member will say something like, “8, 2, 9, and 6.” To which I’ll reply in three seconds or less, “The number you scratched out was a 2.”

Then I’ll turn to someone else and ask which numbers were not scratched out. She’ll say something like, “3, 2, 0, and 7.” I’ll answer, “You scratched out a 6.”

As discussed in a previous post, the difference found by the audience member must be a multiple of 9. Since the sum of the digits of a multiple of 9 must also be a multiple of 9, the magician can quickly figure out the missing digit. In the previous example, . Since the next multiple of 9 after 12 is 18, the magician knows that the missing digit is

.

To speed things up (and to reduce the possibility of a mental arithmetic mistake), the magician doesn’t actually have to add up all of the digits. If the audience member gives a digit of either 0 or 9, then the magician can ignore that digit for purposes of the trick. Likewise, if the magician notices that some subset of the given digits add up to 9, then those digits can be effectively ignored. In the current example, the magician could ignore the 0 and also the 2 and 7 (since ). That leaves only the 3, and clearly one needs to add 6 to 3 to get the next multiple of 9.

I was a little curious about how often this happens — how often the magician can get away with these shortcuts to find the missing digits. So I did some programming in Mathematica. Here’s what I found. If the audience starts with a 5-digit number, so that the difference must be some multiple of 9 between 9 and 99,999:

- There are 690 multiples (out of 11,111, or about 6%) that do not reduce at all (for example, 57,888). So the magician can expect to do the full addition about one-sixth of the time.

- There are 5535 multiples (about 50%) whose digits can be divided into subsets that sum to 9. So, about half the time, the magician can expect to quickly find the missing digit without having to add past 9.

I’ve put on my mathematical wish-list some kind of theorem about this splitting of digits of multiples of 9s.