Numerical integration is a standard topic in first-semester calculus. From time to time, I have received questions from students on various aspects of this topic, including:

- Why is numerical integration necessary in the first place?

- Where do these formulas come from (especially Simpson’s Rule)?

- How can I do all of these formulas quickly?

- Is there a reason why the Midpoint Rule is better than the Trapezoid Rule?

- Is there a reason why both the Midpoint Rule and the Trapezoid Rule converge quadratically?

- Is there a reason why Simpson’s Rule converges like the fourth power of the number of subintervals?

In this series, I hope to answer these questions. While these are standard questions in a introductory college course in numerical analysis, and full and rigorous proofs can be found on Wikipedia and Mathworld, I will approach these questions from the point of view of a bright student who is currently enrolled in calculus and hasn’t yet taken real analysis or numerical analysis.

In the previous post in this series, I discussed three different ways of numerically approximating the definite integral , the area under a curve

between

and

.

In this series, we’ll choose equal-sized subintervals of the interval . If

is the width of each subinterval so that

, then the integral may be approximated as

using left endpoints,

using right endpoints, and

using the midpoints of the subintervals. We have also derived the Trapezoid Rule

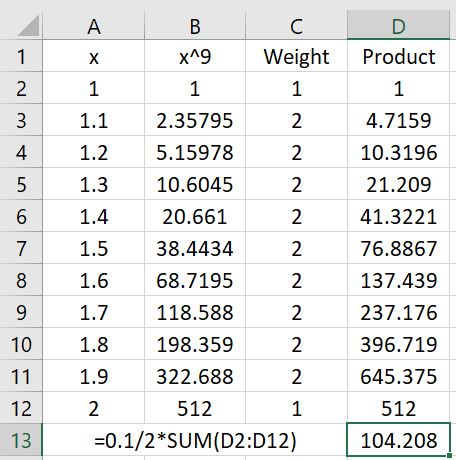

and Simpson’s Rule (if is even)

.

In the previous post in this series, we saw that both the left-endpoint and right-endpoint rules have a linear rate of convergence: if twice as many subintervals are taken, then the error appears to go down by a factor of 2. If ten times as many subintervals are used, then the error should go down by a factor of 10. However, the Midpoint Rule has a quadratic rate of convergence: if twice as many subintervals are taken, then the error appears to go down by a factor of 4. If ten times as many subintervals are used, then the error should go down by a factor of 100.

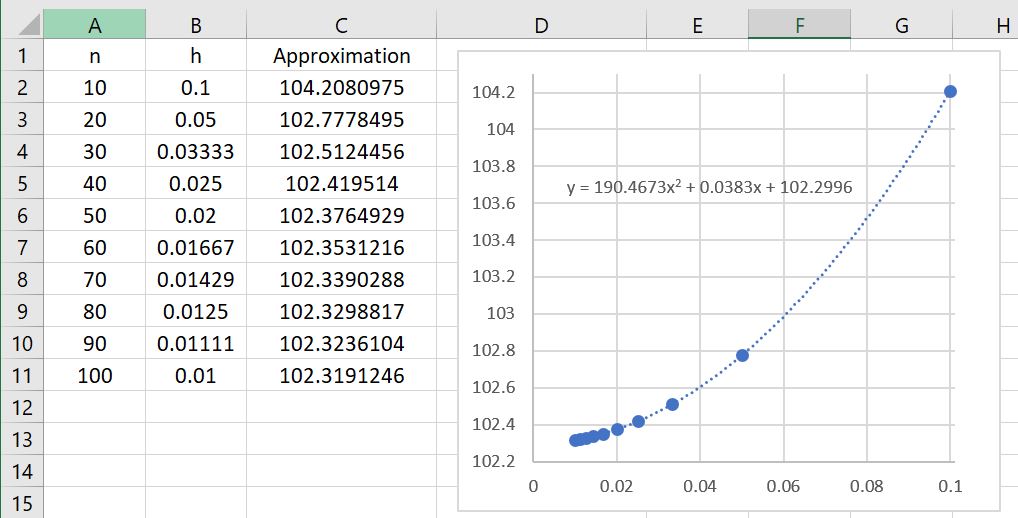

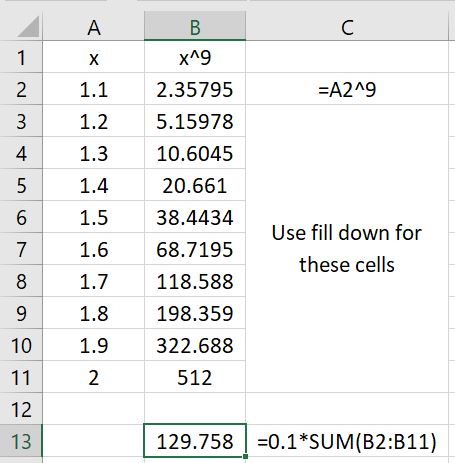

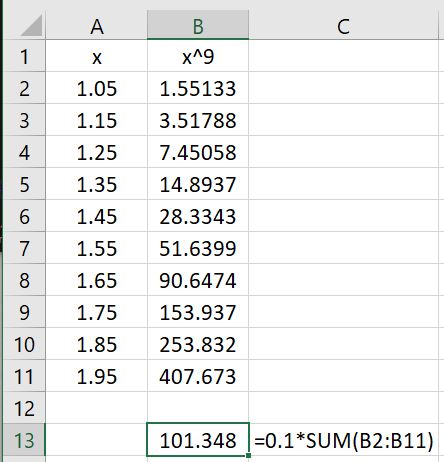

Let’s now explore the results of the Trapezoid Rule applied to using different numbers of subintervals. The results are summarized in the table below.

Once again, the data points fit a quadratic polynomial well, indicating quadratic convergence.

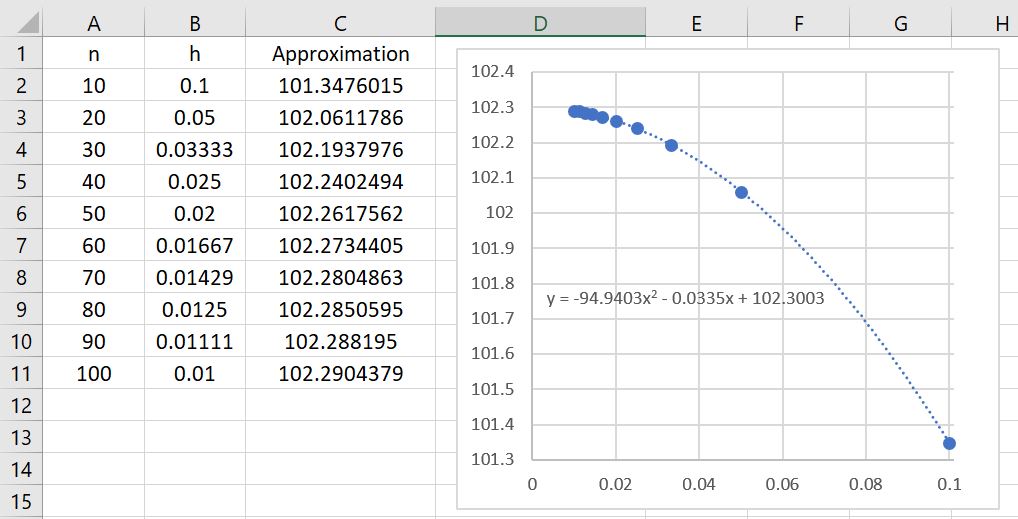

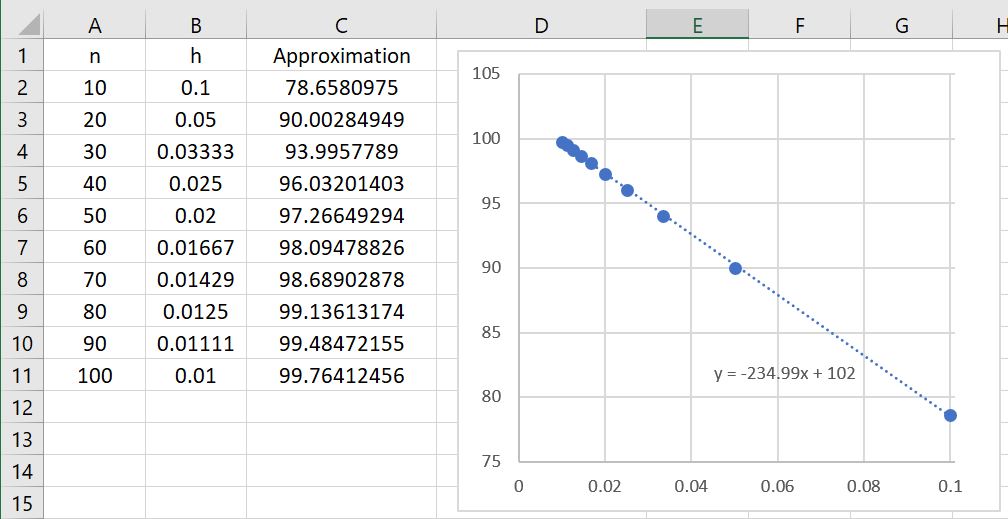

More subtly, it appears that the Trapezoid Rule isn’t quite as good as the Midpoint Rule. Here are the results from the Midpoint Rule (which also appeared in the previous post in this series):

For subintervals, the error of the Trapezoid Rule is

, which the error from the Midpoint Rule is

. In other words, while both of these methods are superior to the left- and right-endpoint rules, it appears that the error from the Midpoint Rule is about half of the error from the Trapezoid Rule. The Midpoint Rule appears to be better.

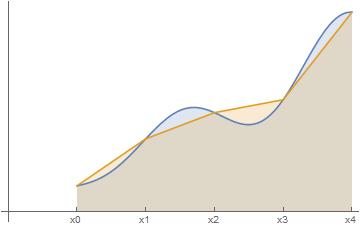

To me, this is far from an obvious conclusion. Geometrically, it’s far from clear that the rectangles from the Midpoint Rule…

… provide a better approximation than using trapezoids …

… yet it appears that’s exactly what happened. This can be rigorously proven, as we’ll explore later in this series.