In a recent class with my future secondary math teachers, we had a fascinating discussion concerning how a teacher should respond to the following question from a student:

Is it ever possible to prove a statement or theorem by proving a special case of the statement or theorem?

Usually, the answer is no… even checking many special cases of a conjecture does not mean that the conjecture is correct.

In yesterday’s post, we showed that the conjecture “ is a prime number for all positive integers

” is true for

but fails for

. In today’s post, I’ll describe a conjecture that is true for plenty more special cases before becoming false.

The Pólya conjecture (see here and here for more information) stated that 50% or more of the natural numbers less than or equal to any given number have an odd number of prime factors (counting multiplicity). For example:

has one prime factor: odd

has one prime factor: odd

has two prime factors: even

has one prime factor: odd

has two prime factors: even

has one prime factor: odd

has three prime factors: odd

has two prime factors: even

has two prime factors: even

So of the numbers less than or equal to 10, five have an odd number of prime factors, and only four have an even number of prime factors.

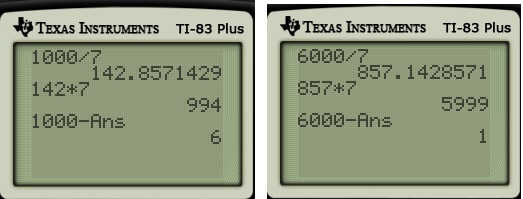

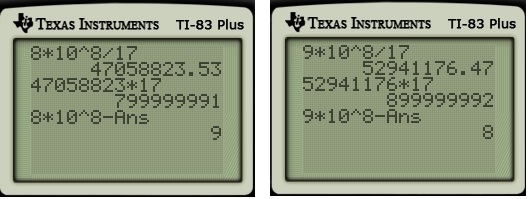

The Pólya conjecture was first proven false by producing a counterexample in the vicinity of . It turns out that the smallest counterexample is 906,150,257. In other words, the Pólya conjecture is true for the first 906,150,256 cases but fails on the next case.