From the video’s description: “Data scientist Cathy O’Neil provides a glimpse of the methods that Netflix, Google, and others apply to recommend or offer to users selections based on their apparent interests.” This is a non-intuitive but real application of linear algebra.

Category: Technology

Preparation for Industrial Careers in the Mathematical Sciences: Finding the Safest Place to Store Nuclear Waste

The Mathematical Association of America recently published a number of promotional videos showing various mathematics can be used in “the real world.” Here’s the first pair of videos describing the process of mathematical modeling. From the YouTube descriptions:

Dr. Genetha Gray talks about her path and about a research problem that she worked on at Sandia National Laboratories. Using quite limited geological data, they had to create a groundwater flow computational model, with parameters to be determined, so that they could study the feasibility and safety of prospective subsurface nuclear waste storage sites.

Prof. Gwen Spencer of Smith College introduces the mathematics behind optimization, calibration, and the quantification of uncertainty in models and in the results that they give.

Arithmetic with big numbers: Index

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on doing basic arithmetic with very large numbers that exceed the character displays of most calculators.

Part 1: Addition

Part 2: Multiplication

Part 3: Division

A clean computer programming joke

A programmer calls home. His wife says, “While you’re out, get some milk.” He never returns home.

Calculator Errors: When Close Isn’t Close Enough (Index)

I’m using the Twelve Days of Christmas (and perhaps a few extra days besides) to do something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on how I remind students about Taylor series. I often use this series in a class like Differential Equations, when Taylor series are needed but my class has simply forgotten about what a Taylor series is and why it’s important.

Part 1: Propagation of small numerical errors.

Part 2: A tragedy during the 1991 Gulf War that was a direct result of calculator rounding.

Square roots and Logarithms Without a Calculator: Index

I’m using the Twelve Days of Christmas (and perhaps a few extra days besides) to do something that I should have done a long time ago: collect past series of posts into a single, easy-to-reference post. The following posts formed my series on computing square roots and logarithms without a calculator.

Part 1: Method #1: Trial and error.

Part 2: Method #2: An algorithm comparable to long division.

Part 3: Method #3: Introduction to logarithmic tables. At the time of this writing, this is the most viewed page on my blog.

Part 4: Finding antilogarithms with a table.

Part 5: Pedagogical and historical thoughts on log tables.

Part 6: Computation of square roots using a log table.

Part 7: Method #4: Slide rules

Part 8: Method #5: By hand, using a couple of known logarithms base 10, the change of base formula, and the Taylor approximation .

Part 9: An in-class activity for getting students comfortable with logarithms when seen for the first time.

Part 10: Method #6: Mentally… anecdotes from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman and me.

Part 11: Method #7: Newton’s Method.

Arithmetic with big numbers (Part 3)

In the previous two posts, we considered the use of base- arithmetic so that a calculator can solve addition and multiplication problems that it ordinarily could not handle. Today, we turn to division. Let’s now consider the decimal representation of

.

There’s no obvious repeating pattern. But we know that, since 17 has neither 2 nor 5 as a factor, that there has to be a repeating decimal pattern.

So… what is it?

When I ask this question to my students, I can see their stomachs churning a slow dance of death. They figure that the calculator didn’t give the answer, and so they have to settle for long division by hand.

That’s partially correct.

However, using the ideas presented below, we can perform the long division extracting multiple digits at once. Through clever use of the calculator, we can quickly obtain the full decimal representation even though the calculator can only give ten digits at a time.

Let’s now return to where this series began… the decimal representation of using long division. As shown below, the repeating block has length

, which can be found in a few minutes with enough patience. By the end of this post, we’ll consider a modification of ordinary long division that facilitates the computation of really long repeating blocks.

Because we arrived at a repeated remainder, we know that we have found the repeating block. So we can conclude that .

Students are taught long division in elementary school and are so familiar with the procedure that not much thought is given to the logic behind the procedure. The underlying theorem behind long division is typically called the division algorithm. From Wikipedia:

Given two integers

and

, with

, there exist unique integers

and

such that

and $0 \le r < |b|$, where

denotes the absolute value of

.

The number is typically called the quotient, while the number

is called the remainder.

Repeated application of this theorem is the basis for long division. For the example above:

Step 1.

. Dividing by

,

Step 2.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Step 1, we see that

Step 3.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Step 2, we see that

And so on.

By adding an extra zero and using the division algorithm, the digits in the decimal representation are found one at a time. That said, it is possible (with a calculator) to find multiple digits in a single step by adding extra zeroes. For example:

Alternate Step 1.

. Dividing by

,

Alternate Step 2.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Alternate Step 1, we see that

So, with these two alternate steps, we arrive at a remainder of and have found the length of the repeating block.

The big catch is that, if or

and

, the appropriate values of

and

have to be found. This can be facilitated with a calculator. The integer part of

and

are the two quotients needed above, and subtraction is used to find the remainders (which must be less than

, of course).

At first blush, it seems silly to use a calculator to find these values of and

when a calculator could have been used to just find the decimal representation of

in the first place. However, the advantage of this method becomes clear when we consider fractions who repeating blocks are longer than 10 digits.

Let’s now return to the question posed at the top of this post: finding the decimal representation of

Let’s now return to the question posed at the top of this post: finding the decimal representation of . As noted in Part 6 of this series, the length of the repeating block must be a factor of

, where

is the Euler toitent function, or the number of integers less than

that are relatively prime with

. Since

is prime, we clearly see that

. So we can conclude that the length of the repeating block is a factor of

, or either

,

,

,

, or

.

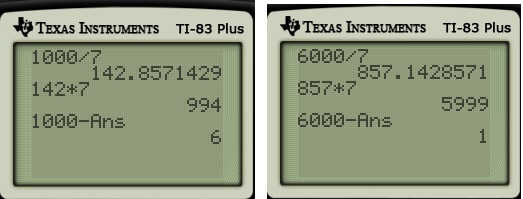

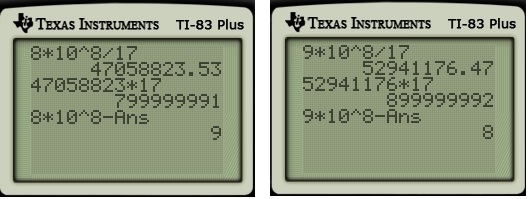

Here’s the result of the calculator again:

We clearly see from the calculator that the repeating block doesn’t have a length less than or equal to . By process of elimination, the repeating block must have a length of

digits.

Now we perform the division algorithm to obtain these digits, as before. This can be done in two steps by multiplying by .

So, by the same logic used above, we can conclude that

In other words, through clever use of the calculator, the full decimal representation can be quickly found even if the calculator itself returns only ten digits at a time… and had rounded the final of the repeating block up to

.

(Note: While this post continues exploring the unorthodox use of a calculator to handle arithmetic problems, it also appeared in a previous series on the decimal expansions of rational numbers.)

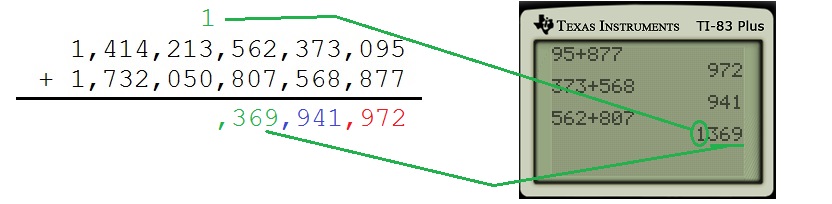

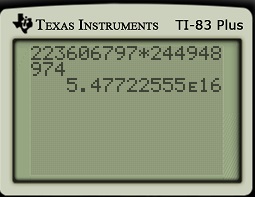

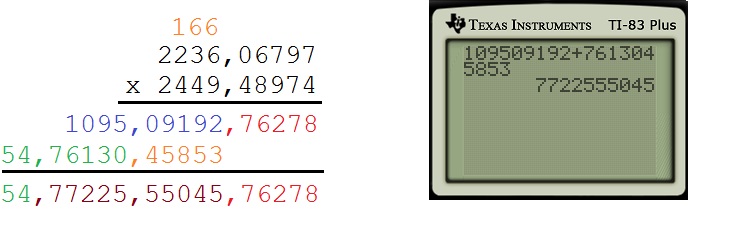

Arithmetic with big numbers (Part 2)

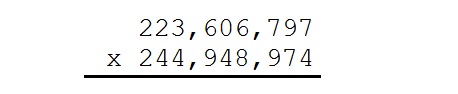

Ready for an elementary arithmetic problem? Here it is:

Nothing to it… just multiply the two numbers. Of course, we’d rather not multiply them by hand, so let’s use a calculator instead:

Uh oh… the calculator doesn’t give the complete answer. It does return the first nine significant digits, but it doesn’t return all 16 digits. Indeed, we can’t be sure that the final 5 in the answer is correct because of rounding.

So now what we do (other than buy a more expensive calculator)?

In yesterday’s post, I posed a similar problem involving addition. Adding two big numbers by hand is no big deal. However, multiplying two big numbers, one digit at time, would be tedious!

When I pose this question to students, the knee-jerk reaction is to groan when facing the prospect of multiplying these two big numbers by hand. However, it is possible to use modern technology to make ordinary grade-school multiplication move a lot quicker. Perhaps the fastest way to do this is to split the numbers into block of five digits instead of the usual three:

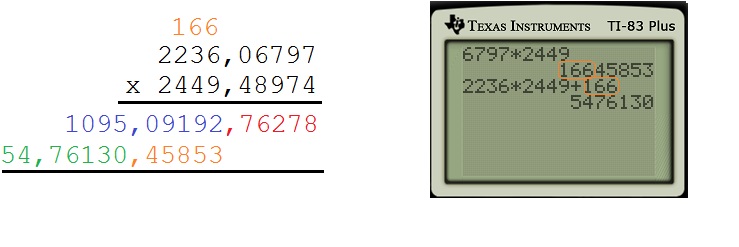

Now we proceed as if each block of five digits was a single digit. We begin with the last block of digits on the second row, which is 48974. First, we multiply 6797 and 48974 using a calculator. Because most modern scientific calculators have a 10-digit display, we can be assured that the complete answer will be shown. (This is why I chose to divide the numbers using block of five digits and not six or more.) The last five digits in the answer are written down; the more significant digits are carried.

Next, we multiply 2236 and 48974 and then add the number that was carried.

We then repeat using 2449, the next (and final) block of digits on the second row. First, we multiply 6797 and 2449 using a calculator. The last five digits in the answer are written down; the more significant digits are carried.

We then repeat using 2449, the next (and final) block of digits on the second row. First, we multiply 6797 and 2449 using a calculator. The last five digits in the answer are written down; the more significant digits are carried.

Next, we multiply 2236 and 2449 and then add the number that was carried.

Finally, it remains to add these two partial products to obtain the final product. For this problem, this can be accomplished with only a single addition: the block of digits 76278 simply carry down to the final answer, and so we can start by adding the second and third blocks of digits. As this sum is less than , there is no digit to carry, and so the leading 54 also carries down to the final answer.

The above technique is logically equivalent to using base 100,000 as opposed to the customary use of base 10 arithmetic. So while multiplying two numbers in the billions still takes some time, judiciously using a calculator makes this exercise go a lot quicker than the ordinary grade-school method of multiplying one digit at a time.

The above technique is logically equivalent to using base 100,000 as opposed to the customary use of base 10 arithmetic. So while multiplying two numbers in the billions still takes some time, judiciously using a calculator makes this exercise go a lot quicker than the ordinary grade-school method of multiplying one digit at a time.

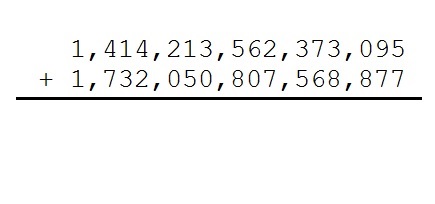

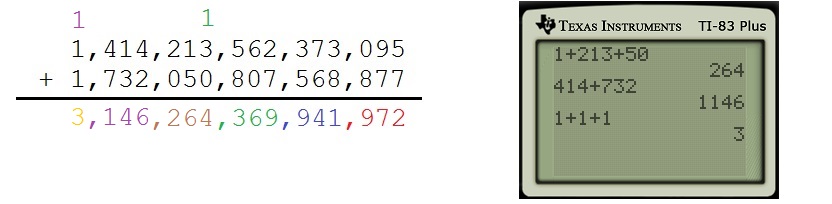

Arithmetic with big numbers (Part 1)

Ready for an elementary arithmetic problem? Here it is:

Nothing to it… just add the two numbers. Of course, we’d rather not add them by hand, so let’s use a calculator instead:

Uh oh… the calculator doesn’t give the complete answer. It does return the first nine significant digits, but it doesn’t return all 16 digits. Indeed, we can’t be sure that the final 7 in the answer is correct because of rounding.

So now what we do (other than buy a more expensive calculator)?

When I pose this question to students, the knee-jerk reaction is to just start adding one digit at a time. Though that’s not the worst possible response, it is possible to use modern technology to make ordinary grade-school addition move a lot quicker. One way to do this is to take three digits at a time while using a calculator:

Notice that the 1 in 1369 gets carried over to the next block of three digits in much the same way that a sum greater than 10 has the tens digit carried over to the next digit. Continuing:

This is logically equivalent to using base 1000 to add these two numbers (as opposed to base 10) and is certainly a lot faster than using only one digit at a time. Of course, it’d go even faster if we use up to nine digits a time (which is equivalent to using base one billion).

This is logically equivalent to using base 1000 to add these two numbers (as opposed to base 10) and is certainly a lot faster than using only one digit at a time. Of course, it’d go even faster if we use up to nine digits a time (which is equivalent to using base one billion).

Inverse Functions: Logarithms and Complex Numbers (Part 30)

Ordinarily, there are no great difficulties with logarithms as we’ve seen with the inverse trigonometric functions. That’s because the graph of satisfies the horizontal line test for any

or

. For example,

,

and we don’t have to worry about “other” solutions.

However, this goes out the window if we consider logarithms with complex numbers. Recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. This is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

Over the past few posts, we developed the following theorem for computing in the case that

is a complex number.

Definition. Let be a complex number so that

. Then we define

.

Of course, this looks like what the definition ought to be if one formally applies the Laws of Logarithms to . However, this complex logarithm doesn’t always work the way you’d think it work. For example,

.

This is analogous to another situation when an inverse function is defined using a restricted domain, like

or

.

The Laws of Logarithms also may not work when nonpositive numbers are used. For example,

,

but

.

This material appeared in my previous series concerning calculators and complex numbers: https://meangreenmath.com/2014/07/09/calculators-and-complex-numbers-part-21/