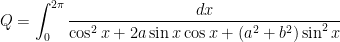

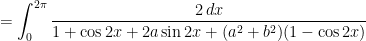

Originally, my wife had asked me to compute this integral by hand because Mathematica 4 and Mathematica 8 gave different answers. At the time, I eventually obtained the solution by multiplying the top and bottom of the integrand by

and then employing the substitution

(after using trig identities to adjust the limits of integration).

But this wasn’t the only method I tried. Indeed, I tried two or three different methods before deciding they were too messy and trying something different. So, for the rest of this series, I’d like to explore different ways that the above integral can be computed.

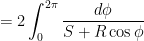

Here’s my progress so far:

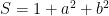

where this last integral is taken over the complex plane on the unit circle, a closed contour oriented counterclockwise. Also,

and

,

,

are the two distinct roots of the denominator (as long as  ). In these formulas,

). In these formulas, and

and  . (Also,

. (Also,  is a certain angle that is now irrelevant at this point in the calculation).

is a certain angle that is now irrelevant at this point in the calculation).

This contour integral looks more complicated; however, it’s an amazing fact that integrals over closed contours can be easily evaluated by only looking at the poles of the integrand. For this integral, that means finding the values of  where the denominator is equal to 0, and then determining which of those values lie inside of the closed contour.

where the denominator is equal to 0, and then determining which of those values lie inside of the closed contour.

Let’s now see if either of the two roots of the denominator lies inside of the unit circle in the complex plane. In other words, let’s determine if  and/or

and/or  .

.

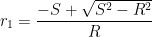

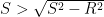

I’ll begin with  . Clearly, the numbers

. Clearly, the numbers  ,

,  , and

, and  are the lengths of three sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse

are the lengths of three sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse  . So, since the hypotenuse is the longest side,

. So, since the hypotenuse is the longest side,

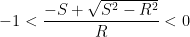

or

so that

.

.

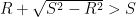

Also, by the triangle inequality,

Combining these inequalities, we see that

,

,

and so I see that  , so that

, so that  does lie inside of the contour

does lie inside of the contour  .

.

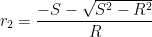

The second root  is easier to handle:

is easier to handle:

.

.

Therefore, since  lies outside of the contour, this root is not important for the purposes of computing the above contour integral.

lies outside of the contour, this root is not important for the purposes of computing the above contour integral.

Now that I’ve identified the root that lies inside of the contour, I now have to compute the residue at this root. I’ll discuss this in tomorrow’s post.

Now that I’ve identified the root that lies inside of the contour, I now have to compute the residue at this root. I’ll discuss this in tomorrow’s post.

Since

Since , there are three separate cases that have to be considered:

,

, and

. I’ll begin with the easiest case of

. In this case, the integral

is easy to evaluate:

since I used the assumption that

.