Last March, on Pi Day (March 14, 2015), I put together a mathematical magic show for the Pi Day festivities at our local library, compiling various tricks that I teach to our future secondary teachers. I was expecting an audience of junior-high and high school students but ended up with an audience of elementary school students (and their parents). Still, I thought that this might be of general interest, and so I’ll present these tricks as well as the explanations for these tricks in this series. From start to finish, this mathematical magic show took me about 50-55 minutes to complete. None of the tricks in this routine are original to me; I learned each of these tricks from somebody else.

Here’s the patter for my fourth and most impressive trick. As before, my audience has a sheet of paper and a pen or pencil; quite a few of them have calculators.

Write down any five-digit number you want. Just make sure that the same digit repeated (not something like 88,888).

(pause)

Now scramble the digits of your number, and write down the new number. Just be sure that any repeated digits appear the same number of times. (For example, if your first number was 14,232, your second number could be 24,231 or 13,422.)

(pause)

Is everyone done? Now subtract the smaller of the two numbers from the bigger, and write down the difference. Use a calculator if you wish.

(pause)

Has everyone written down the difference. Good. Now, pick any nonzero digit in the difference, and scratch it out.

(pause)

(I point to someone.) Which numbers did you not scratch out?

The audience member will say something like, “8, 2, 9, and 6.” To which I’ll reply in three seconds or less, “The number you scratched out was a 2.”

Then I’ll turn to someone else and ask which numbers were not scratched out. She’ll say something like, “3, 2, 0, and 7.” I’ll answer, “You scratched out a 6.”

After performing this trick, I’ll explain how it works. I gave a very mathematical explanation in a previous post for why this trick works, but the following explanation seems to go over well with even elementary-school students. I’ll ask an audience member for the two five-digit numbers that they subtracted. Suppose that she tells me that hers were

After performing this trick, I’ll explain how it works. I gave a very mathematical explanation in a previous post for why this trick works, but the following explanation seems to go over well with even elementary-school students. I’ll ask an audience member for the two five-digit numbers that they subtracted. Suppose that she tells me that hers were

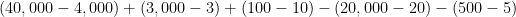

I’ll now tell the audience that, ordinarily, we would plug this into a calculator or else start by subtracting the ones digits. However, I tell the audience, I’m now going to write this in a very unusual way:

I tell the audience, “For now, I’m not saying why I did this. But does everyone agree that I can do this?” Once I get agreement, then I proceed to the next step by grouping like digits together:

Again, I tell the audience, “For now, I’m not saying why I did this. But does everyone agree that I can do this?” Once I get agreement, then I proceed to the next step by reversing the signs of any negative differences:

Next, I factor each common difference. Notice that in each parenthesis, the second number is a factor of the first number:

,

,

or

.

.

Notice that the number in each pair of parentheses is a multiple of 9. Therefore, no matter what, the difference must be a multiple of 9.

This is the key observation that makes the trick work. Now, I go back to my audience member and ask what the difference actually was:

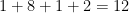

This difference must be a multiple of 9. Therefore, by one of the standard divisibility tricks, the digits of this number must add to a multiple of 9:

.

.

Then I’ll ask the audience member, “Which number did you scratch out?” Suppose she answers 6. Then I’ll add up the remaining numbers:

.

.

So I ask the audience, “So these four numbers add up to 12, but I know that all five numbers have to add up to a multiple of 9. What’s the next multiple of 9 after 12?” They’ll answer, “18”. I ask, “So what does the missing number have to be?” They’ll answer “18-12, or 6.”

Then I’ll repeat with someone else. If an audience member answers “8, 2, 9, and 6,” I’ll ask the audience for the sum of these four numbers. (It’s 25.) So they can figure out that the scratched-out number was 2, since 25+2 = 27 is the next multiple of 9 after 25.

I’m often asked why I made people choose a five-digit number at the start of the routine. The answer is, I could have chosen any size number I wanted as long as I’m comfortable with quickly adding the digits at the end of the magic trick. In other words, if I had permitted nine-digit numbers, I might need to add 8 numbers at the end of the routine to get the missing number. I could do it, but I wouldn’t get the answer as quickly as the five-digit numbers.

I’m often asked why I made people choose a five-digit number at the start of the routine. The answer is, I could have chosen any size number I wanted as long as I’m comfortable with quickly adding the digits at the end of the magic trick. In other words, if I had permitted nine-digit numbers, I might need to add 8 numbers at the end of the routine to get the missing number. I could do it, but I wouldn’t get the answer as quickly as the five-digit numbers.

Also, I’m often asked why it was important that I told the audience to scratch out a nonzero number. Well, suppose that I came to end of the routine and the audience member told me her remaining digits were 4, 3, and 2. These numbers have a sum of 9, and so the missing number hypothetically could be 0 or 9. So by instructing the audience to not scratch out a 0, that eliminates the ambiguity from this special case.

After showing the audience how the trick works, I’ll then ask an audience member to come forward and repeat the trick that I just performed. Then I’ll move on to the final act of my routine, which I’ll present in tomorrow’s post.

I encourage the reader to develop another set of cards for base 5. It will require 10 cards for numbers from 1 to 24.

I encourage the reader to develop another set of cards for base 5. It will require 10 cards for numbers from 1 to 24.