In this series of posts, I explore properties of complex numbers that explain some surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems using a calculator (see video at the bottom of this post). These posts form the basis for a sequence of lectures given to my future secondary teachers.

Definition. If  is a complex number, then we define

is a complex number, then we define

Even though this isn’t the usual way of defining the exponential function for real numbers, the good news is that one Law of Exponents remains true. (At we saw in an earlier post in this series, we can’t always assume that the usual Laws of Exponents will remain true when we permit the use of complex numbers.)

Theorem. If  and

and  are complex numbers, then

are complex numbers, then  .

.

In yesterday’s post, I gave the idea behind the proof… group terms where the sums of the exponents of  and

and  are the same. Today, I will formally prove the theorem.

are the same. Today, I will formally prove the theorem.

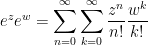

The proof of the theorem relies on a principle that doesn’t seem to be taught very often anymore… rearranging the terms of a double sum. In this case, the double sum is

This can be visualized in the picture below, where the  axis represents the values of

axis represents the values of  and the

and the  axis represents the values of

axis represents the values of  . Each red dot symbolizes a term in the above double sum. For a fixed value of

. Each red dot symbolizes a term in the above double sum. For a fixed value of  , the values of

, the values of  vary from

vary from  to

to  . In other words, we start with

. In other words, we start with  and add all the terms on the line

and add all the terms on the line  (i.e., the

(i.e., the  axis in the picture). Then we go up to

axis in the picture). Then we go up to  and then add all the terms on the next horizontal line. And so on.

and then add all the terms on the next horizontal line. And so on.

I will rearrange the terms as follows: Let  . Then for a fixed value of

. Then for a fixed value of  , the values of

, the values of  will vary from

will vary from  to

to  . This is perhaps best described in the picture below. The value of

. This is perhaps best described in the picture below. The value of  , the sum of the coordinates, is constant along the diagonal lines below. The value of

, the sum of the coordinates, is constant along the diagonal lines below. The value of  then changes while moving along a diagonal line.

then changes while moving along a diagonal line.

Even though this is a different way of adding the terms, we clearly see that all of the red circles will be hit regardless of which technique is used for adding the terms.

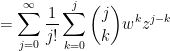

In this way, the double sum  gets replaced by

gets replaced by  . Since

. Since  , we have

, we have

We now add a couple of  terms to this expression for reasons that will become clear shortly:

terms to this expression for reasons that will become clear shortly:

Since  does not contain any

does not contain any  s, it can be pulled outside of the inner sum on

s, it can be pulled outside of the inner sum on  . We do this for the

. We do this for the  in the denominator:

in the denominator:

We recognize that  is a binomial coefficent:

is a binomial coefficent:

The inner sum is recognized as the formula for a binomial expansion:

Finally, we recognize this as the definition of  , using the dummy variable

, using the dummy variable  instead of

instead of  . This proves that

. This proves that  even if

even if  and

and  are complex.

are complex.

Without a doubt, this theorem was a lot of work. The good news is that, with this result, it will no longer be necessary to explicitly use the summation definition of  to actually compute

to actually compute  , as we’ll see tomorrow.

, as we’ll see tomorrow.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.

is

and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. As noted before, this is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

, where

and

are real numbers, then

be a complex number so that

. Then we define

.

and

are complex numbers so that

. Then we define

and

are real numbers.

. For the base of

, we note that

.

,

. To begin,

.

, and

in a single problem.