Sadly, at least at my university, Taylor series is the topic that is least retained by students years after taking Calculus II. They can remember the rules for integration and differentiation, but their command of Taylor series seems to slip through the cracks. In my opinion, the reason for this lack of retention is completely understandable from a student’s perspective: Taylor series is usually the last topic covered in a semester, and so students learn them quickly for the final and quickly forget about them as soon as the final is over.

Of course, when I need to use Taylor series in an advanced course but my students have completely forgotten this prerequisite knowledge, I have to get them up to speed as soon as possible. Here’s the sequence that I use to accomplish this task. Covering this sequence usually takes me about 30 minutes of class time.

I should emphasize that I present this sequence in an inquiry-based format: I ask leading questions of my students so that the answers of my students are driving the lecture. In other words, I don’t ask my students to simply take dictation. It’s a little hard to describe a question-and-answer format in a blog, but I’ll attempt to do this below.

In the previous posts, I described how I lead students to the definition of the Maclaurin series

,

,

which converges to  within some radius of convergence for all functions that commonly appear in the secondary mathematics curriculum.

within some radius of convergence for all functions that commonly appear in the secondary mathematics curriculum.

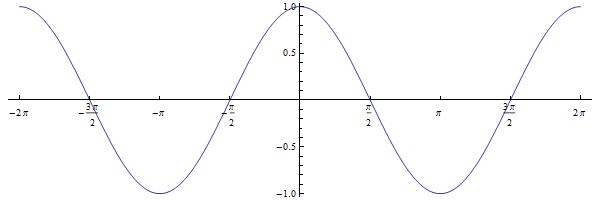

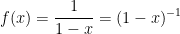

Step 5. That was easy; let’s try another one. Now let’s try  .

.

What’s  ? Plugging in, we find

? Plugging in, we find  .

.

Next, to find  , we first find

, we first find  . Using the Chain Rule, we find

. Using the Chain Rule, we find  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next, we differentiate again:  , so that

, so that  .

.

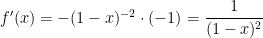

Hmmm… no obvious pattern yet… so let’s keep going.

For the next term,  , so that

, so that  .

.

For the next term,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Oohh… it’s the factorials again! It looks like  , and this can be formally proved by induction.

, and this can be formally proved by induction.

Plugging into the series, we find that

.

.

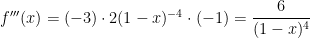

Like the series for  , this series converges quickest for

, this series converges quickest for  . Unlike the series for

. Unlike the series for  , this series does not converge for all real numbers. As can be checked with the Ratio Test, this series only converges if

, this series does not converge for all real numbers. As can be checked with the Ratio Test, this series only converges if  .

.

The right-hand side is a special kind of series typically discussed in precalculus. (Students often pause at this point, because most of them have forgotten this too.) It is an infinite geometric series whose first term is $1$ and common ratio $x$. So starting from the right-hand side, one can obtain the left-hand side using the formula

by letting  and $r=x$. Also, as stated in precalculus, this series only converges if the common ratio satisfies $|r| < 1$, as before.

and $r=x$. Also, as stated in precalculus, this series only converges if the common ratio satisfies $|r| < 1$, as before.

In other words, in precalculus, we start with the geometric series and end with the function. With Taylor series, we start with the function and end with the series.

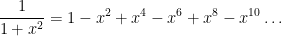

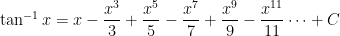

Step 6. A whole bunch of other Taylor series can be quickly obtained from the one for  . Let’s take the derivative of both sides (and ignore the fact that one should prove that differentiating this infinite series term by term is permissible). Since

. Let’s take the derivative of both sides (and ignore the fact that one should prove that differentiating this infinite series term by term is permissible). Since

and

,

,

we have

.

.

____________________

Next, let’s replace  with

with  in the Taylor series in Step 5, obtaining

in the Taylor series in Step 5, obtaining

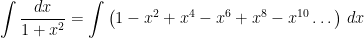

Now let’s take the indefinite integral of both sides:

To solve for the constant of integration, let  :

:

Plugging back in, we conclude that

The Taylor series expansion for  can be found by replacing

can be found by replacing  with

with  :

:

Subtracting, we find

My understanding is that this latter series is used by calculators when computing logarithms.

____________________

Next, let’s replace  with

with  in the Taylor series in Step 5, obtaining

in the Taylor series in Step 5, obtaining

Now let’s take the indefinite integral of both sides:

To solve for the constant of integration, let  :

:

Plugging back in, we conclude that

____________________

In summary, a whole bunch of Taylor series can be extracted quite quickly by differentiating and integrating from a simple infinite geometric series. I’m a firm believer in minimizing the number of formulas that I should memorize. Any time I personally need any of the above series, I’ll quickly use the above steps to derive them from that of  .

.

and

can be found using the formula

.

and

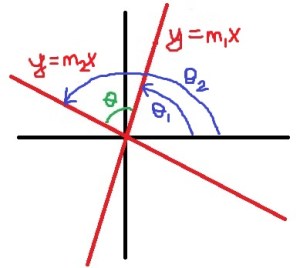

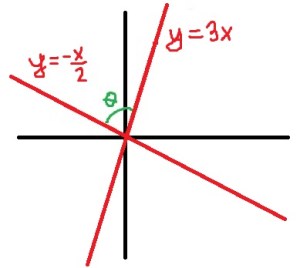

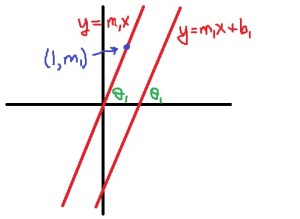

, and let’s measure the angle that the line makes with the positive

axis.

The lines

The lines and

are parallel, and the

axis is a transversal intersecting these two parallel lines. Therefore, the angles that both lines make with the positive

axis are congruent. In other words, the

is entirely superfluous to finding the angle

. The important thing that matters is the slope of the line, not where the line intersects the

axis.

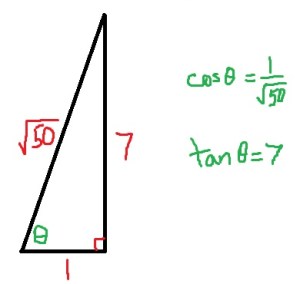

lies on the line

, which also passes through the origin. By definition of tangent,

can be found by dividing the

and

coordinates:

.

intercepts do not matter, and so we only need to find the smallest angle between the lines

and

.

will either be equal to

or

, depending on the values of

and

. Let’s now compute both

and

using the formula for the difference of two angles:

must lie between

and

, the value of

must be positive (or undefined if

… for now, we’ll ignore this special case). Therefore, whichever of the above two lines holds, it must be that

and

:

is undefined at

, and the right hand side is also undefined if

. This matches the theorem that the two lines are perpendicular if and only if

, or that the slopes of the two lines are negative reciprocals.