In this series of posts, I’d like to describe what I tell my students on the very first day of Calculus I. On this first day, I try to set the table for the topics that will be discussed throughout the semester. I should emphasize that I don’t hold students immediately responsible for the content of this lecture. Instead, this introduction, which usually takes 30-45 minutes, depending on the questions I get, is meant to help my students see the forest for all of the trees. For example, when we start discussing somewhat dry topics like the definition of a continuous function and the Mean Value Theorem, I can always refer back to this initial lecture for why these concepts are ultimately important.

I’ve just told students that the topics in Calculus I build upon each other (unlike the topics of Precalculus), but that there are going to be two themes that run throughout the course:

- Approximating curved things by straight things, and

- Passing to limits

I then transition to applying these two themes to two different problems. Here’s the first.

Problem #1. A building on campus is 144 feet tall. A professor takes a particularly annoying student to the top of the building, and throws him (or her) off to his (or her) certain demise. (Usually I pick a student that I know and like as the one to throw off the building. This became a badge of honor over the years.) The distance that the student travels (in feet) after  seconds is

seconds is  . How fast is the student going when he (or she) hits the concrete sidewalk?

. How fast is the student going when he (or she) hits the concrete sidewalk?

And then I ask my students how to solve this. Usually, they can come up with the first few ideas.

1. When the student hits the sidewalk and meet his/her demise? So we must solve  , so that

, so that  . (And I make sure that they remember that this quadratic equation has two roots.) The solution

. (And I make sure that they remember that this quadratic equation has two roots.) The solution  is clearly extraneous, so the time elapsed until the student meets his/her demise is

is clearly extraneous, so the time elapsed until the student meets his/her demise is  seconds.

seconds.

2. How fast is the student going after  seconds? Most students realize the inherent difficulty of this question because the student’s speed is increasing as he/she gets closer to the ground. Some students will volunteer the word “accelerate.”

seconds? Most students realize the inherent difficulty of this question because the student’s speed is increasing as he/she gets closer to the ground. Some students will volunteer the word “accelerate.”

At this point, I’ll volunteer that the changing speed is a curved thing. Back in pre-algebra, students were taught

under the assumption that the rate was constant. However, if the rate is changing, all bets are off.

Still, the question remains: how fast is the student moving after 3 seconds? How should we measure this? Usually, someone will suggest that we just divide  feet by

feet by  seconds, for a rate of

seconds, for a rate of  ft/sec. I then point out that this is an example of approximating a curved thing by a straight thing. The straight thing is the usual distance-rate-time formula, while the curved thing is the changing speed of the student as he/she falls. So the answer of

ft/sec. I then point out that this is an example of approximating a curved thing by a straight thing. The straight thing is the usual distance-rate-time formula, while the curved thing is the changing speed of the student as he/she falls. So the answer of  ft/sec is not the correct answer, but it’s an approximate answer.

ft/sec is not the correct answer, but it’s an approximate answer.

This leads to the next question: is this estimate too high or too low? Unequivocally, students answer “too low” since the student travels the slowest at the start of the fall and the fastest at the end of the fall. So since this interval of 3 seconds includes the slower speeds at the start of the fall, the answer of  ft/sec will underestimate the speed at impact.

ft/sec will underestimate the speed at impact.

Which then leads to the next obvious question: How can we get a better approximation? I leave the question open-ended like this and take suggestions from the class. This often takes a while, and I’ll get a lot of creative (but bad) ideas. And that’s OK… the next step is hardly the most intuitive thing that immediately jumps to mind. I think that the process of keeping the answer unknown until someone volunteers the correct next step is worth it.

Eventually (though it might take a couple of minutes), somebody will suggest using a shorter time interval, like the distance traveled between  and

and  . We see that

. We see that  and

and  , and so the new approximation is

, and so the new approximation is  ft/s. I store these two approximations (

ft/s. I store these two approximations ( ft/s with a time interval of

ft/s with a time interval of  seconds and

seconds and  ft/s with a time interval of

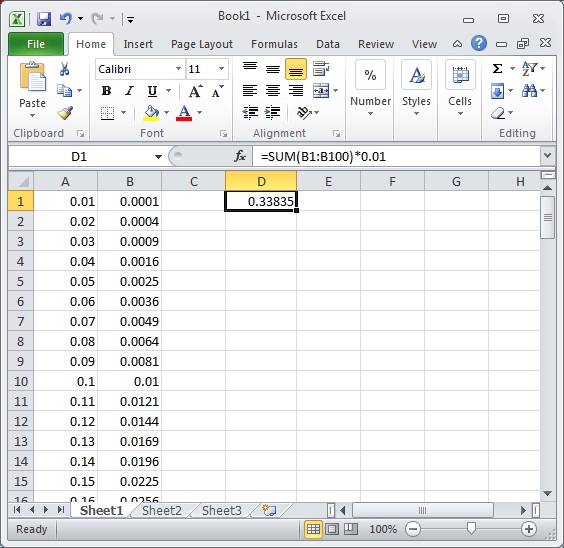

ft/s with a time interval of  second in a table on the side of the chalkboard. The values derived below are entered in the table as they’re found.

second in a table on the side of the chalkboard. The values derived below are entered in the table as they’re found.

I then note that the previous approximation was  ft/s, and then ask the class, “Do you think that

ft/s, and then ask the class, “Do you think that  ft/s will be a better or worse approximation than

ft/s will be a better or worse approximation than  ft/s?” Invariably, they’ll say it’s a better approximation because the change in speed isn’t as great from

ft/s?” Invariably, they’ll say it’s a better approximation because the change in speed isn’t as great from  to

to  as from

as from  to

to  . I’ll then ask if they think that

. I’ll then ask if they think that  ft/s is too high or too low. Again, they’ll answer too low for the same reason as before.

ft/s is too high or too low. Again, they’ll answer too low for the same reason as before.

Then I ask the obvious next question, “How do we find a better approximation?” The class typically responds something to the effect of, “Take a smaller interval.” I ask for a suggestion, and I’ll usually get something like  to

to  . We see that

. We see that  ft/s and

ft/s and  is still

is still  ft/s, so that the new approximation is

ft/s, so that the new approximation is  ft/s. Students will volunteer that this should be better than the previous two approximations but still less than the correct answer.

ft/s. Students will volunteer that this should be better than the previous two approximations but still less than the correct answer.

Then I do it again: “How do we find a better approximation?” The class typically respond, “Take an even smaller interval.” I suggest  to

to  . We see that

. We see that  ft/s (by this point, a calculator is certainly needed) and

ft/s (by this point, a calculator is certainly needed) and  is still

is still  ft/s, so that the new approximation is

ft/s, so that the new approximation is  ft/s. If we do it again with

ft/s. If we do it again with  , we see that

, we see that  ft/s, for an approximation of

ft/s, for an approximation of  ft/s.

ft/s.

I turn to the class and ask, “Have we found the right answer yet?” They’ll answer “No” in unison, but they’ll note that the approximations are probably pretty good right now. Astute students will notice that the approximations appear to be “leveling off” to some final value.

I’ll then tell the class that this is an example of passing to limits, the second theme of calculus. By making the time intervals smaller and smaller, we get better and better approximations to the true speed at impact. In the next post, I’ll describe how I informally introduce the concept of a limit with this example.