In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Marissa Arevalo. Her topic, from Precalculus: graphing an ellipse.

How have different cultures throughout time used this topic in their society?

In a philosophy paper, I wrote a about the usage of ellipses that applied not only to the field of mathematics but theology and science (more specifically astronomy), and the implications it had throughout time. Throughout centuries, mankind has argued over the ways of the universe and whether or not we are the center of that universe or if something else is. From the times of Ancient Greece, Aristotle believed that the center of our universe revolved around a form of unchanging matter that did not obey the laws of the planet earth. Ptolemy rejected this idea and created a model of a universe centered around Earth itself where the other planets revolved around us, but he could not answer as to why the planetary orbits did not follow a circular path. Later on in the 14th and 15th centuries Copernicus and Galileo respectively argued for a system that orbited the sun rather than the Earth. This idea went against the beliefs of the church and their research caused Galileo to be held into persecution for his radical ideas (Copernicus died before any due harm came to him). It was not until Johannes Kepler, under the tutelage of his teacher Tycho Brahe, observed the motion of the planet Mars and noted that the path did not actually follow a circular path but an elliptical one. His findings disproved his teacher, who was a firm advocate of the church and believed in a geocentric model, showing that the planets were centered around the sun. Sir Isaac Newton’s Laws of Gravity later proved Kepler’s theories, and to this day are known as Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion.

We utilize these laws and other properties in order to define what it means to be a planet, therefore a planet:

- Must be round in physical shape

- Must have an elliptical path around the sun

- Must be able to clear anything that comes into its orbital path

These properties defined all of our planets, except Pluto, who it was discovered to be smaller than other things that existed in its orbit in the Kuiper Belt and therefore cannot have the third property. While the orbital pattern of Pluto followed the guidelines of the other planets (though with a greater eccentricity), Pluto was too small, therefore removing it off the list of planets in the solar system in 2006 and was defined as a “dwarf planet”. While the students of this time may not relate to the surprise of the reclassification of Pluto in our solar system, it is still relatable to today’s society as this long debate of the way planets move and how our universe was created greatly impacts science even today as we make new discoveries over other celestial bodies in our universe.

How can technology (YouTube, Khan Academy [khanacademy.org]. Vi Hart, Geometers, graphing calculators, etc.) be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

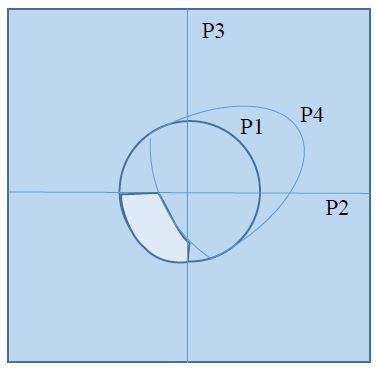

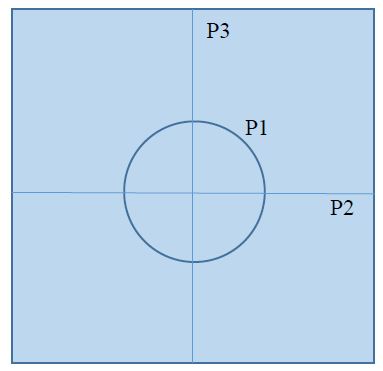

A website that can be utilized for students to get more involved in their own learning would be Gizmos where the students can be given a small exploration sheet in which they can compare the graph of ellipse to its equation and what exactly affects the shape of the ellipse as different aspects are altered. The students can also manipulate the graph and watch the standard form of the equation change over time. The site allows the student to also see the pythagorean and geometric relationships and definitions of an ellipse as the equation is altered. One very important key feature on the exploration of the geometric definition is that the student is able to plot the purple point that moves along the edge of the figure in different locations to show the relationship between the lengths of foci from the edge. The only downside may be that while the teacher can use the site for a short free trial, they may have to make payments in order to continue using it. Desmos is another website that can graph ellipse equations, but it does not provide the ability to see the geometric definition applied to the graph of the function.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

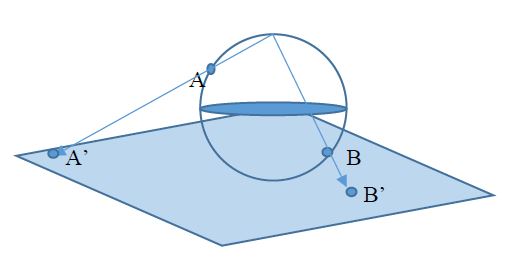

Another idea that would have the students thinking about the geometric concepts surrounding the properties of an ellipse would be for the teacher to have worksheets in which the students would show the representation of where an ellipse could be formed in the cutting of double-napped cone with a plane. The students could lead discussions in their own ideas and how an ellipse, hyperbola, parabola, and circle are created if you literally sliced the cones into pieces. The teacher could have either a physical model of the cones or have the students create the physical model of the cones with play-doh and cut the cones with cardboard/plastic-wear/dental floss (preferred) and describe the shape that was created in by the cuts made. (Another idea is to make the cones with Rice Krispies or scones and jam/chocolate) The good thing about this play-doh is approximately 50 cents at Wal-Mart and provide a nice way for students to make mistakes and restart without having to clean that big of a mess up. The students will be more involved in the material if they are able to create physical models and form their own ideas on things that many teachers do not address in their lessons. This is coming from personal experience of not knowing certain geometric properties of conic sections until taking college courses.

References:

https://www.desmos.com/calculator

https://illuminations.nctm.org/uploadedFiles/Content/Lessons/Resources/9-12/CuttingConics-AS.pdf

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/480759328950528032/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/343540277799331864/

https://www.explorelearning.com/index.cfm?method=cResource.dspView&ResourceID=132

http://mste.illinois.edu/courses/ci399TSMsu03/folders/jmpeter1/Daily%20Assignments/Conic%20Sections/Ellipse%20Paper%20Folding(CI399).html

Cain, F. (2012). Why Pluto is No Longer a Planet – Universe Today. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://www.universetoday.com/13573/why-pluto-is-no-longer-a-planet/

Helden, A. V. (2016, February 17). Galileo. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Galileo-Galilei

Jones, A. R. (n.d.). Ptolemaic system. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://

http://www.britannica.com/topic/Ptolemaic-system

Leveillee, N. P. (2011). Copernicus, Galileo, and the Church: Science in a Religious World.

Student Pulse, 3(5), 1-2. Retrieved March 15, 2016, from http://www.studentpulse.com/

articles/533/copernicus-galileo-and-the-church-science-in-a-religious-world

Rosenburg, M. (2015, April 22). Scientiflix. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://

scientiflix.com/post/117082918519/keplers-first-law-of-motion-elliptical-orbits

Simmons, B. (2016, February 21). Mathwords: Foci of an Ellipse. Retrieved March 22, 2016,

from http://www.mathwords.com/f/foci_ellipse.htm

The Universe of Aristotle and Ptolemy. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://

csep10.phys.utk.edu/astr161/lect/retrograde/aristotle.html

Westman, R. S. (2016, February 21). Johannes Kepler. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Johannes-Kepler

The projection of four planes:

The projection of four planes: