Last March, on Pi Day (March 14, 2015), I put together a mathematical magic show for the Pi Day festivities at our local library, compiling various tricks that I teach to our future secondary teachers. I was expecting an audience of junior-high and high school students but ended up with an audience of elementary school students (and their parents). Still, I thought that this might be of general interest, and so I’ll present these tricks as well as the explanations for these tricks in this series. From start to finish, this mathematical magic show took me about 50-55 minutes to complete. None of the tricks in this routine are original to me; I learned each of these tricks from somebody else.

In the last couple of posts, I discussed a trick for predicting the number of triangles that appear when a convex gon with

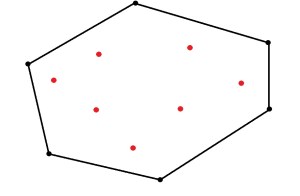

points in the middle is tesselated. Though I probably wouldn’t do the following in a magic show (for the sake of time), this is a natural inquiry-based activity to do with pre-algebra students in a classroom setting (as opposed to an entertainment setting) to develop algebraic thinking. I’d begin by giving the students a sheet of paper like this:

Then I’ll ask them to start on the left box. I’ll tell them to draw a triangle in the box and place one point inside, and then subdivide into smaller triangles. Naturally, they all get 3 triangles.

Then I ask them to repeat if there are two points inside. Everyone will get 5 triangles.

Then I ask them to repeat until they can figure out a pattern. When they figure out the pattern, then they can make a prediction about what the rest of the chart will be.

Then I’ll ask them what the answer would be if there were 100 points inside of the triangle. This usually requires some thought. Eventually, the students will get the pattern for the number of triangles if the initial figure is a triangle.

Then I’ll repeat for a quadrilateral (with four sides instead of three). After some drawing and guessing, the students can usually guess the pattern .

Then I’ll repeat for a pentagon. After some drawing and guessing, the students can usually guess the pattern .

Then I’ll have them guess the pattern for the hexagon without drawing anything. They’ll usually predict the correct answer, .

What about if the outside figure has 100 sides? They’ll usually predict the correct answer, .

What if the outside figure has sides? By now, they should get the correct answer,

.

This activity fosters algebraic thinking, developing intuition from simple cases to get a pretty complicated general expression. However, this activity is completely tractable since it only involves drawing a bunch of figures on a piece of paper.