This series of posts concerns solving the following problem from the 2016 University of Maryland High School Mathematics Competition.

A sphere is divided into regions by 9 planes that are passing through its center. What is the largest possible number of regions that are created on its surface?

a.

b.

c. 81

d. 76

e. 74

This series was actually written by my friend Jeff Cagle, department head for mathematics at Chapelgate Christian Academy, as he tried technique after technique to solve this problem. I thought that his resolution to the problem was an excellent example of the process of mathematical problem-solving, and (with his permission) I am posting the process of his solution here. (For the record, I have no doubt that I would not have been able to solve this problem.)

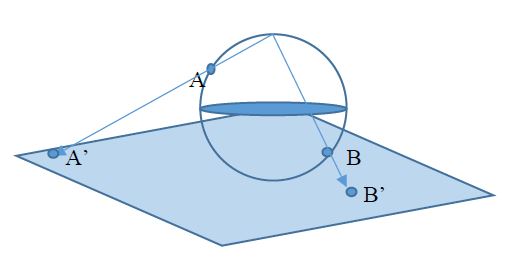

OK, so I wanted to prove that each region would be a triangle. So I decided to project the sphere onto a plane.

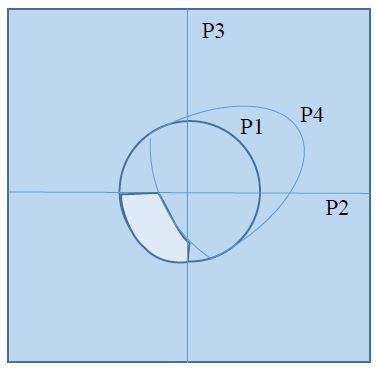

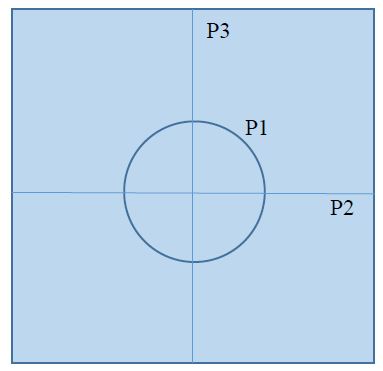

The projection of four planes:

The projection of four planes:

After a while, I had a chart for max possible regions.

- 1 plane: Max regions = 2

- 2 planes: Max regions = 4

- 3 planes: Max regions = 8 (exponential?)

- 4 planes: Max regions = 14 (nope!)

- 5 planes: Max regions = 22 (huh?)

Then, really because I had no other ideas, I tried counting intersection points AND max regions

(remembering that one intersection point is “at infinity” – that is, the north pole).

- 1 plane: Intersection Points = 0, Max regions = 2

- 2 planes: Intersection Points = 2, Max regions = 4

- 3 planes: Intersection Points = 6, Max regions = 8

- 4 planes: Intersection Points = 12, Max regions = 14

- 5 planes: Intersection Points 20, Max regions = 22

Oh. My. Goodness. The max regions are simply the number of intersection points plus 2. Could it really REALLY be that simple?