Category: Algebra II

Combinatorics and Jason’s Deli (Part 2)

Jason’s Deli is one of my family’s favorite places for an inexpensive meal. Recently, I saw the following placard at our table advertising their salad bar:

The small print says “Math performed by actual rocket scientist”; let’s see how the rocket scientist actually did this calculation.

The advertisement says that there are 50+ possible ingredients; however, to actually get a single number of combinations, let’s say there are exactly 50 ingredients. Lettuce will serve as the base, and so the 5 ingredients that go on top of the lettuce will need to be chosen from the other 49 ingredients.

Also, order is not important for this problem… for example, it doesn’t matter if the tomatoes go on first or last if tomatoes are selected for the salad.

Therefore, the number of possible ingredients is

,

or the number in the 5th column of the 49th row of Pascal’s triangle. Rather than actually finding the 49th row of Pascal’s triangle by direct addition, it’s simpler to use factorials:

.

Under the assumption that there are exactly 50 ingredients, the rocket scientist actually got this right.

Combinatorics and Jason’s Deli (Part 1)

Jason’s Deli is one of my family’s favorite places for an inexpensive meal. Recently, I saw the following placard at our table advertising their salad bar:

I share this in the hopes that this might be reasonably engaging for students learning about different methods of counting.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8g)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

So far, I’ve used Pascal’s triangle to obtain

.

.

.

.

.

I’m almost done… except my students wanted me to find the square root of this number without using a calculator.

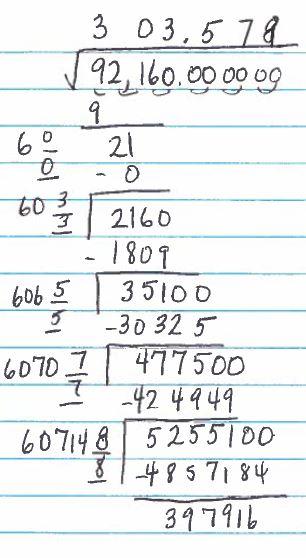

There are a couple ways to do this; the method I chose was directly extracting the square root by hand… a skill that was taught to children in previous generations but has fallen out of pedagogical disfavor with the advent of handheld calculators. I lost my original work, but it would have looked something like this (see the above website for details on why this works):

And so I gave my students their answer:

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8f)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

So far, I’ve used Pascal’s triangle to obtain

.

.

.

.

To numerically evaluate , I use the identity

;

this identity can be proven by using the binomial theorem

and then plugging in and

. Using this identity, I conclude that

.

Since I know that , it’s now a simple matter of multiplication:

.

(Trust me; after I showed my students this answer about five minutes after it was posed, I was ecstatic when I confirmed this answer with Mathematica.)

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8e)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

So far, I’ve used Pascal’s triangle to obtain

.

.

.

.

In the first series, I’ll rewrite as

. Also, in the second series, I’ll rewrite

as

. Therefore,

We now see that binomial coefficients appear in each of these series:

I’ll conclude the evaluation of in tomorrow’s post.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8d)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

So far, I’ve used Pascal’s triangle to obtain

.

I now use the definition of the binomial coefficient:

.

Since and

, this simplifies as

.

In the first series, I’ll use the change of index , so that

and

. Also, in the first series, the index will change from

to

to

to

.

In the second series, I’ll use the change of index , so that

and

. Also, in the first series, the index will change from

to

to

to

.

With these changes, I obtain

.

I’ll continue the simplification of these series in tomorrow’s post.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8c)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

In yesterday’s post, I explained how Pascal’s triangle can be used to conclude

,

thus allowing me to get the top number without getting all of the intermediate steps.

To compute this sum without a calculator, I’ll start rearranging the terms. The reasons for rearranging the terms in this way will become evident later.

.

The terms of the first sum are clearly equal to 0 when and

. Also, the $k=0$ term of the second sum is clearly 0. Therefore,

.

It doesn’t look like I’ve improved matters much with this rearrangement of ; I’ll continue the solution in tomorrow’s post.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 8b)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting. They wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

Here’s how I started the problem, using a trick that I use in my mathematical magic show. Suppose that there are only six numbers instead of twelve, and let the six numbers be ,

,

,

,

, and

. Then here’s how the triangle unfolds (turning the triangle upside down):

In other words, the top number can be obtained by using the numbers on the fifth row of Pascal’s triangle (recall that the fifth row of Pascal’s triangle has six numbers on it). Specifically, if I multiply the bottom numbers by the corresponding number in a row of Pascal’s triangle and add them up, I’ll get the number on top without having to compute all of the intermediate steps.

For the problem my students gave me, the bottom row has 12 numbers, which means I’ll need to use the 11th row of Pascal’s triangle. Also, as we’ll see, I was fortunate that my students gave me a simple pattern of consecutive squares for the numbers on the bottom row. Since the numbering in Pascal’s triangle starts on zero, the numbers in the bottom row are as

varies from 0 to 11.

Putting all this together, I can conclude that

.

Beginning with tomorrow’s post, I’ll discuss how I computed this sum without a calculator.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary school students (Part 8a)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received, in the students’ original handwriting:

Here’s the explanation that my students told me (but didn’t write down): they wanted me to add adjacent numbers on the bottom row to produce the number on the next row, building upward until I reached the apex of the triangle. For example, the lower-left portion of the triangle would build like this (since 1+4=5, 4+9=13, 9+16=25, etc.):

56

18 38

5 13 25

1 4 9 16

Then, after I reached the top number, they wanted me to take the square root of that number. (Originally, they wanted me to first multiply by 80 before taking the square root, but evidently they decided to take it easy on me.)

And, just to see if I could do it, they wanted me to do all of this without using a calculator. But they were nice and allowed me to use pencil and paper.

And I produced the answer in less than five minutes.

I’ll reveal how I got the answer so quickly in this series. In the meantime, I’ll leave a thought bubble if you’d like to think about it on your own.