In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Taylor Bigelow. Her topic, from Pre-Algebra: making and interpreting bar charts, frequency charts, pie charts, and histograms.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Charts allow for a lot of fun class activities. For example, we can have them take their own data for a table and create charts from that data. For my activity, I will give them all dice, which they should be very familiar with, and have them roll the dice 20 times and keep track of how many times it lands on each number in a table. From that table, they will make their own bar charts, frequency charts, and pie charts. After they roll their dice and make their charts, they will then answer questions interpreting the charts. This tests their ability to understand data and make all the different types of charts.

How has this topic appeared in the news?

Charts are all over in the news, especially recently. There were pie charts and frequency charts all over during the election cycle, and with covid, all we see is bar charts of covid data. An easy engage for this topic would be to make observations about these types of graphs that they’ll probably see all the time during election seasons and might even be familiar with. First, we will ask the students what news can benefit from graphs, and what news they have seen graphs in recently. I expect answers similar to elections, covid, and economics. Then we can look at some of the graphs that usually show up around election cycles. We will take a minute as a class to discuss what they notice about the graphs and what they mean. Questions like “what type of graph is this”, “what are the variables in this graph”, and “what information do you get from this graph”. This will show the students that being able to read these graphs has real life applications, and it also teaches them what important things to look for in the graphs during class time and homework.

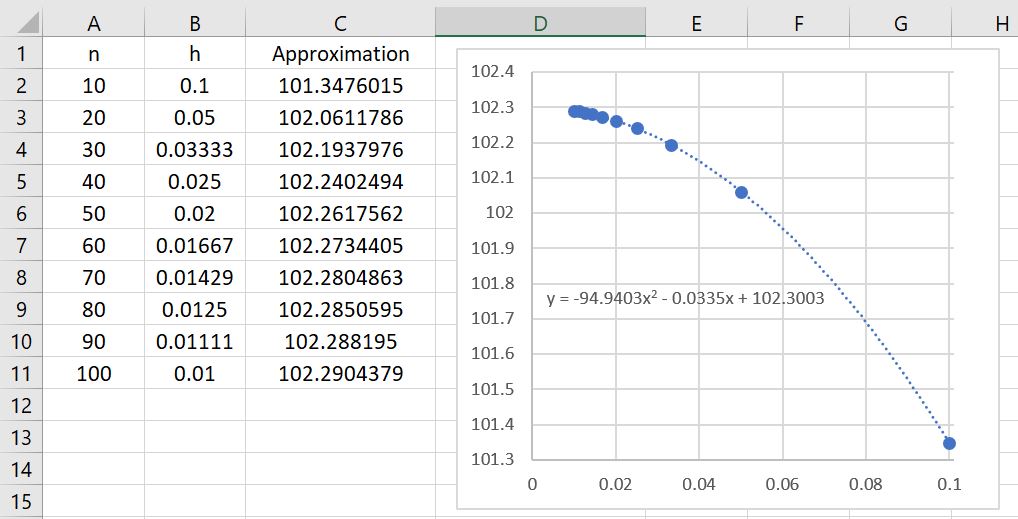

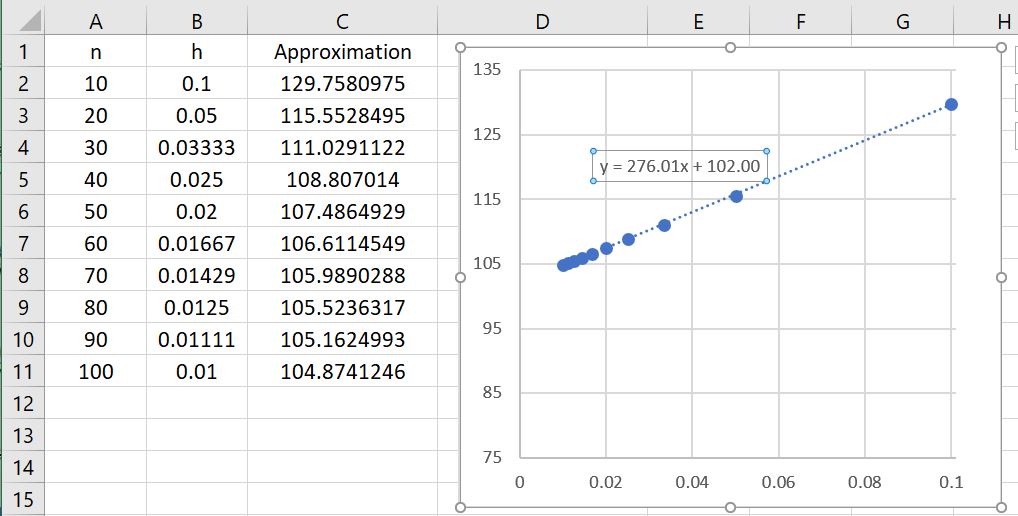

How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

Technology is very useful for making graphs and being able to make and manipulate graphs can help them understand how to interpret the information given in graphs. Google sheets or excel can both be used to make and manipulate graphs. For this activity we would give the students some sample data and have them enter it into an online spreadsheet, and then make an appropriate graph to show this data. They then would answer questions about this graph, like “Why did you choose this type of graph to represent the data?”, “what is the independent variable and what is the dependent variable”, “What observations can you make about this graph?”, and “What would happen if you changed X to be # instead? Or if you added more information?” and other questions, especially about graphs with multiple variables. This helps students see how different information can be represented and lets them experiment with the information on their own, while also answering questions that steer them in the direction that the teacher wants them to know.