I’m in the middle of a series of posts concerning the elementary operation of computing a square root. This is such an elementary operation because nearly every calculator has a button, and so students today are accustomed to quickly getting an answer without giving much thought to (1) what the answer means or (2) what magic the calculator uses to find square roots. I like to show my future secondary teachers a brief history on this topic… partially to deepen their knowledge about what they likely think is a simple concept, but also to give them a little appreciation for their elders.

In Parts 3-5 of this series, I discussed how log tables were used in previous generations to compute logarithms and antilogarithms.

Today’s topic — log tables — not only applies to square roots but also multiplication, division, and raising numbers to any exponent (not just to the power). After showing how log tables were used in the past, I’ll conclude with some thoughts about its effectiveness for teaching students logarithms for the first time.

To begin, let’s again go back to a time before the advent of pocket calculators… say, the 1880s.

Aside from a love of the movies of both Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne, I chose the 1880s on purpose. By the end of that decade, James Buchanan Eads had built a bridge over the Mississippi River and had designed a jetty system that allowed year-round navigation on the Mississippi River. Construction had begun on the Panama Canal. In New York, the Brooklyn Bridge (then the longest suspension bridge in the world) was open for business. And the newly dedicated Statue of Liberty was welcoming American immigrants to Ellis Island.

And these feats of engineering were accomplished without the use of pocket calculators.

Here’s a perfectly respectable way that someone in the 1880s could have computed to reasonably high precision. Let’s write

.

Take the base-10 logarithm of both sides.

.

Then log tables can be used to compute .

Step 1. In our case, we’re trying to find . We know that

and

, so the answer must be between

and

. More precisely,

.

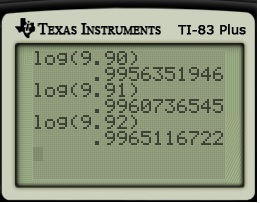

To find , we see from the table that

and

So, to estimate , we will employ linear interpolation. That’s a fancy way of saying “Find the line connecting

and

, and find the point on the line whose

coordinate is

. Finding this line is a straightforward exercise in the point-slope form of a line:

So we estimate . Thus, so far in the calculation, we have

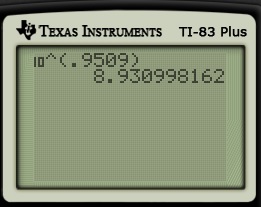

Step 2. We then take the antilogarithm of both sides. The term antilogarithm isn’t used much anymore, but the principle is still taught in schools: take to the power of both the left- and right-hand sides. We obtain

The first part of the right-hand side is easy: . For the second-part, we use the log table again, but in reverse. We try to find the numbers that are closest to

in the body of the table. In our case, we find that

and

.

Once again, we use linear interpolation to find the line connecting and

, except this time the

coordinate of

is known and the

coordinate is unknown.

Since the table is only accurate to four significant digits, we estimate that . Therefore,

By way of comparison, the answer is , rounding at the hundredths digit. Not bad, for a generation born before the advent of calculators.

With a little practice, one can do the above calculations with relative ease. Also, many log tables of the past had a column called “proportional parts” that essentially replaced the step of linear interpolation, thus speeding the use of the table considerably.

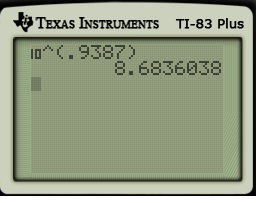

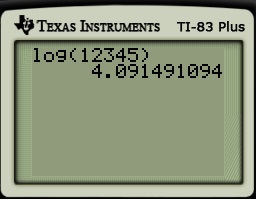

Log tables can be used for calculations more complex than finding a square root. For example, suppose I need to calculate

Using the log table, and without using a calculator, I find that

That’s the correct answer to four significant digits. Using a calculator, we find the answer is