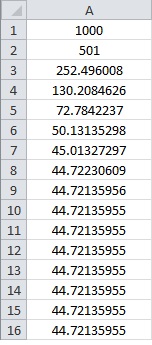

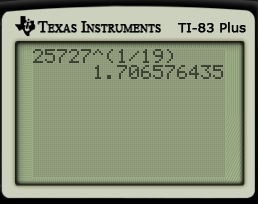

In yesterday’s post, I showed a movie (also provided at the bottom of this post) that calculators can return surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems involving complex numbers. In this series of posts, I hope to explain why the calculator returns these results.

To begin, we recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant.

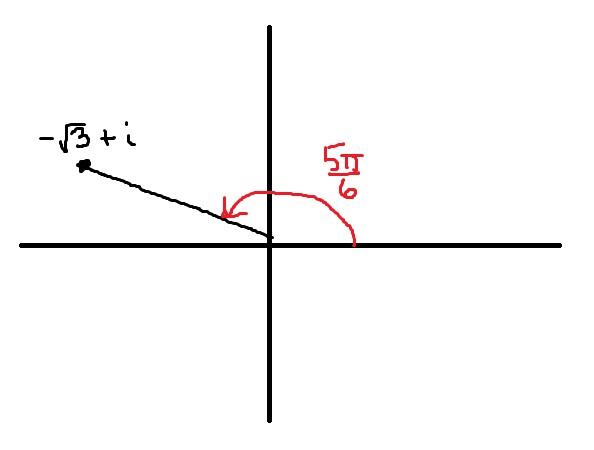

For example, the point is in the second quadrant of the complex plane. The modulus is

.

(Notice that , and not

, appears in the above expression.) Also,

, so that

Since is in the second quadrant, we choose

. Therefore,

This can be checked by simply evaluating the right-hand side and distributing:

When teaching this in class, I’ll run through about 2-4 more examples to make sure that this concept is stuck in my students’ heads.

Notes:

- The angle

is not uniquely defined… any angle that is coterminal with

would also have worked. For example,

and

- It’s really important to remember that

need not be equal to

. After all, the arctangent of an angle must lie between

and

, which won’t work for complex numbers in either the second or third quadrant. That said, it is true that

- The above procedure is also the essence of converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates (or vice versa), which is a function pre-programmed on many scientific calculators.

- When teaching this topic, I often use physical humor to get the above points across.

- I’ll pick the direction parallel to the chalkboard to be the positive real axis, and the direction perpendicular to the chalkboard (i.e., pointing toward my students) as the positive imaginary axis. I’ll pick some convenient spot in front of the class to be the origin.

- Standing at the origin, I’ll face the positive real axis, spin in an angle of

, and take two steps to arrive at the point

.

- Returning to the origin, I’ll face the positive real axis, spin the other direction in an angle of

, and take two steps to arrive at the same point.

- Returning to the origin, I’ll face the positive real axis, spin in an angle of

(getting more than a little dizzy while doing so), and take two steps to arrive at the same point.

- Returning to the origin, I’ll face the positive real axis, spin in an angle of only

, and take two steps backwards (while doing the moonwalk) to arrive at the same point.

We will need to use this concept of writing a complex number in trigonometric form in order to explain the calculator’s results. For completeness, here’s the movie that I used to begin this series of posts.