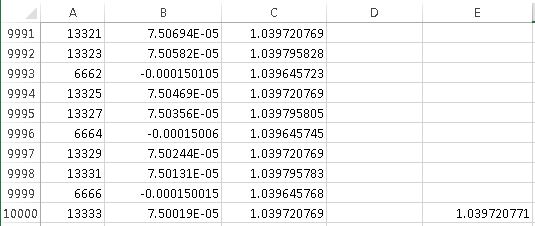

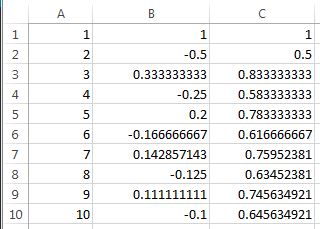

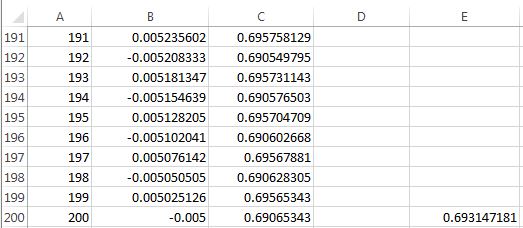

Let’s define partial sums of the harmonic series as follows:

,

where are positive integers. Here are a couple of facts that I didn’t know before reading Gamma (pages 24-25):

is never equal to an integer.

- The only values of

for which

is an integer are

and

.

When I researching for my series of posts on conditional convergence, especially examples related to the constant , the reference Gamma: Exploring Euler’s Constant by Julian Havil kept popping up. Finally, I decided to splurge for the book, expecting a decent popular account of this number. After all, I’m a professional mathematician, and I took a graduate level class in analytic number theory. In short, I don’t expect to learn a whole lot when reading a popular science book other than perhaps some new pedagogical insights.

Boy, was I wrong. As I turned every page, it seemed I hit a new factoid that I had not known before.

In this series, I’d like to compile some of my favorites — while giving the book a very high recommendation.