In this series of posts, I explore properties of complex numbers that explain some surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems using a calculator (see video at the bottom of this post). These posts form the basis for a sequence of lectures given to my future secondary teachers.

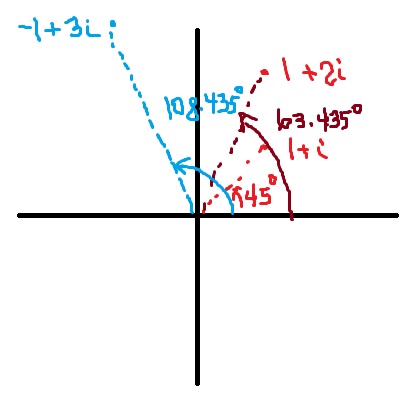

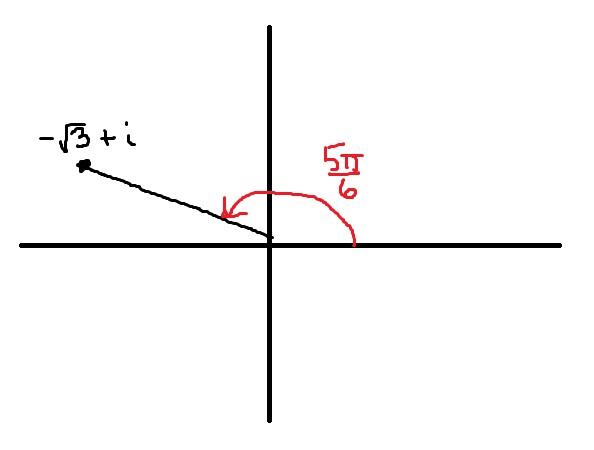

To begin, we recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. As noted before, this is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

In the previous post, I proved the following theorem which provides a geometric interpretation for multiplying complex numbers.

Theorem. .

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there’s also a theorem for dividing complex numbers. Students can using guess the statement of this theorem.

Theorem. .

Proof. The proof begins by separating the and

terms and then multiplying by the conjugate of the denominator:

At this juncture in the proof, there are two legitimate ways to proceed.

Method #1: Multiply out the right-hand side. After all, this is how we proved the theorem yesterday. For this reason, students naturally gravitate toward this proof, and the proof works after recognizing the trig identities for the sine and cosine of the difference of two angles.

However, this isn’t the most elegant proof.

Method #2: I break out my old joke about the entrance exam at MIT and the importance of using previous work. I rewrite the right-hand side as

;

this also serves as a reminder about the odd/even identities for sine and cosine, respectively. Then students observe that the right-hand side is just a product of two complex numbers in trigonometric form, and so the angle of the product is found by adding the angles.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.