The five most important numbers in mathematics are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . In sixth place (a distant sixth place) is probably

. In sixth place (a distant sixth place) is probably  , the Euler-Mascheroni constant. See Mathworld or Wikipedia for more details. (For example, it’s astounding that we still don’t know if

, the Euler-Mascheroni constant. See Mathworld or Wikipedia for more details. (For example, it’s astounding that we still don’t know if  is irrational or not.)

is irrational or not.)

In yesterday’s post, we’ve seen the curious phenomenon that the commutative and associative laws do not apply to a conditionally convergent series or infinite product. In tomorrow’s post, I’ll present another classic example of this phenomenon due to Cauchy. However, to be ready for this fact, I’ll need to see how  arises from a certain conditionally convergent series.

arises from a certain conditionally convergent series.

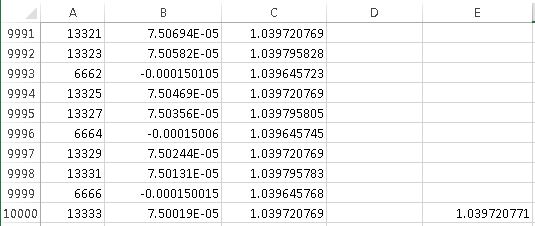

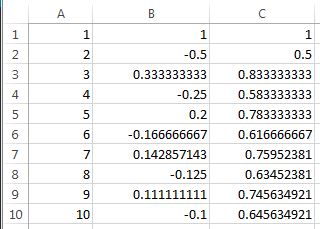

Separately define the even and odd terms of the sequence  by

by

and

.

.

It’s pretty straightforward to show that this sequence is decreasing. The function  is clearly decreasing for

is clearly decreasing for  , and so the maximum value of

, and so the maximum value of  on the interval

on the interval ![[n,n+1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bn%2Cn%2B1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) must occur at the left endpoint, while the minimum value must occur at the right endpoint. Since the length of this interval is

must occur at the left endpoint, while the minimum value must occur at the right endpoint. Since the length of this interval is  , we have

, we have

,

,

or

.

.

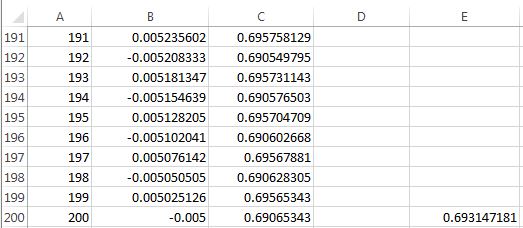

Since the subsequence  clearly decreases to

clearly decreases to  , this shows the full sequence

, this shows the full sequence  is a decreasing sequence with limit

is a decreasing sequence with limit  .

.

By the alternating series test, this implies that the series

converges. This limit is called the

Since this series converges, that means that the limit of the partial sums converges to  :

:

.

.

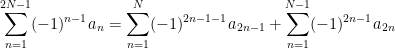

Let’s take the upper limit to be an odd number  , where

, where  and

and  is an integer. Then by separating the even and odd terms, we obtain

is an integer. Then by separating the even and odd terms, we obtain

.

.

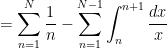

Therefore,

.

.

With this interpretation, the sum can be viewed as the sum of the  rectangles in the above picture, while the integral is the area under the hyperbola. Therefore, the limit

rectangles in the above picture, while the integral is the area under the hyperbola. Therefore, the limit  can be viewed as the limit of the blue part of the above picture.

can be viewed as the limit of the blue part of the above picture.

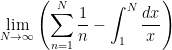

In other words, it’s an amazing fact that while both

and

diverge, somehow the difference

converges… and this limit is defined to be the number  .

.

.