Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received:

What is the chance of winning a game of BINGO after only four turns?

I leave a thought bubble in case you’d like to think this. One way of answering this question appears after the bubble.

When my class posed this question, I was a little concerned that my class was simply not ready to understand the solution (described below), as it takes more than a little work to get at the answer. Still, what I love about this question is that it gave me a way to teach my class some techniques of probabilistic reasoning that probably would not occur in a traditional elementary school setting. Also, I was reminded that even these gifted students might need a little help with simplifying the answer. So let me discuss how I helped these young students discover the answer. I found the ensuing discussion especially enlightening, and so I’m dividing this discussion into several posts.

Here’s a non-standard BINGO board:

Using the free space in the middle, there are four ways of winning the game in four moves:

- Horizontally (11-12-13-14)

- Vertically (3-8-17-22)

- Diagonally (1-7-18-24)

- Diagonally (5-9-16-20)

A standard BINGO board has 75 possible numbers (B 1-15, I 16-30, N 31-45, G 46-60, O 61-75). However, the board that I was using with my class (which was being used for pedagogical purposes) only had 44 possibilities. So the solution below assumes these 44 possibilities; the answer for a standard BINGO board is obvious.

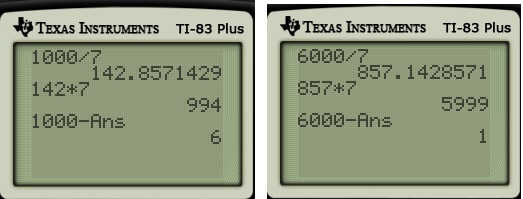

My class quickly decided to start by solving the problem for the horizontal case. I began by asking for the chance that the first number will be on the middle row; after some thought, the class correctly answered .

Next, I asked the chance that the next number would also be on the middle row. To my surprise, this wasn’t automatic for my young but gifted students. They felt that they didn’t know where the first number was, and so they felt like they couldn’t know the chance for the second number. To get them over this conceptual barrier (or so I thought), I asked them to pretend that the first number was 11. Then what would be the odds that the next number fell on the middle row? After some discussion, the class agreed that the answer was .

Once that barrier was cleared, then the class saw that the next two fractions were and

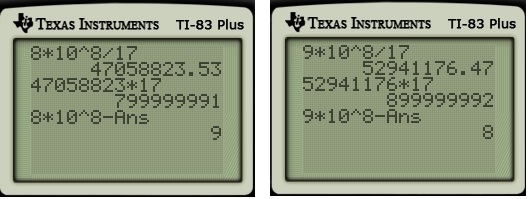

. I then explained that, to get the answer for the four consecutive numbers on the middle row, these fractions have to be multiplied:

I didn’t justify why the fractions had to be multiplied; my class just accepted this as the way to combined the fractions to get the answer for all four events happening at once.

Then I asked about the other three possibilities — the middle column and the two diagonals. The class quickly agreed that the answer should be the same for these other possibilities, and so the final answer should just be four times larger:

At this point, I was ready to go on, but then a student asked something like the following:

At this point, I was ready to go on, but then a student asked something like the following:

Shouldn’t the answer be

? I mean, we chose 11 to be the first number so that we can figure out the chance for the second number, and the chance that the first number is 11 is

.

Oops. While trying to clear one conceptual hurdle (getting the answer of for the second number), I had inadvertently introduced a second hurdle by making my class wonder if the first number had to be a specific number.

I began by trying to explain that the first number really didn’t have to be 11 after all, but that only seemed to re-introduce the original barrier. Finally, I found an answer that my class found convincing: Yes, the chance that the first number is 11, the second number is 12, the third number is 13, and fourth number is 14 is indeed . But there are other ways that all the numbers could land on the middle row:

- The first number could be 12, the second number could be 11, the third number could be 13, and the fourth number could be 14.

- Quickly, light dawned, and my class began volunteering other orderings by which all the numbers land in the middle row.

- We then enumerated the number of ways that this could happen, and we found that the answer was indeed 24.

- I then tied the knot by noting that

, and so gives another explanation for the numerators in the answer.

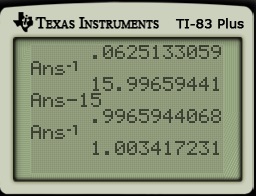

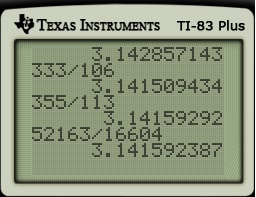

Having found the answer, it was now time to simplify the answer. More on this in tomorrow’s post.

Having found the answer, it was now time to simplify the answer. More on this in tomorrow’s post.