In this series of posts, I provide a deeper look at common applications of exponential functions that arise in an Algebra II or Precalculus class. In the previous posts in this series, I considered financial applications, radioactive decay, and Newton’s Law of Cooling.

Today, I introduce the logistic growth model, which describes how an infection (like a disease, a rumor, or advertise) spreads in a population. For example:

or

Sources: http://www.xkcd.com/1220/ and http://www.xkcd.com/1235/

In yesterday’s post, I described an in-class demonstration that engages students while also making the following formula believable:

.

Where does this formula come from? Suppose that a disease is spreading in a population of size . It stands to reason that the rate at which the disease spreads is proportional to the number of possible contacts between those who have the disease and those who don’t. If

is the number of people who have the disease, then

is the number of people who don’t have the disease. Therefore, the product

is the number of possible contacts between those who have the disease and those who don’t. This leads to the governing differential equation

,

where is the constant of proportionality. This is often rewritten by letting

, or

:

The good news is that this differential equation can be solved using separation of variables, just like the governing differential equations for continuous compound interest, paying off credit card debt, radioactive decay, and Newton’s Law of Cooling. The bad news is that it’s a lot harder to calculate the required integrals! After all, the right-hand side, after distributing, has a term containing , which makes this differential equation non-linear.

Solving this differential equation is a bit tedious, and I don’t feel particularly obligated to re-invent the wheel since it can be found several places on the Internet. Suffice it to say that integration by partial fractions and some very tricky algebra is necessary to solve for and obtain the solution above. Among several different sources (which likely use different letters than the ones I’m using here):

- http://www.math.usu.edu/powell/ysa-html/node8.html

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsYWMEmNmZo

- http://www.math24.net/population-growth.html

- http://www.ugrad.math.ubc.ca/coursedoc/math101/notes/moreApps/logistic.html

- https://www.google.com/search?q=logistic+curve&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a#q=logistic+curve+%22partial+fraction%22&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logistic_function#In_ecology:_modeling_population_growth

MathWorld: http://mathworld.wolfram.com/LogisticEquation.html

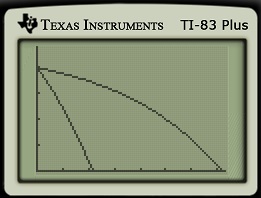

Under the theory that a picture is worth a thousand words, let’s take a look at the graphs of both of these functions:

Under the theory that a picture is worth a thousand words, let’s take a look at the graphs of both of these functions: