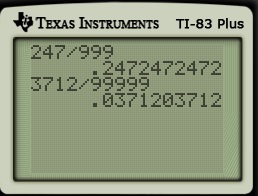

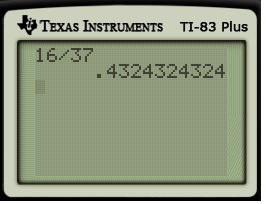

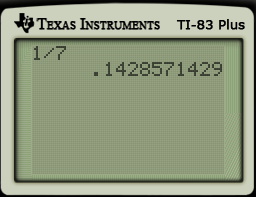

Let’s now consider the decimal representation of .

There’s no obvious repeating pattern. But we know that, since 17 has neither 2 nor 5 as a factor, that there has to be a repeating decimal pattern.

So… what is it?

When I ask this question to my students, I can see their stomachs churning a slow dance of death. They figure that the calculator didn’t give the answer, and so they have to settle for long division by hand.

That’s partially correct.

However, using the ideas presented below, we can perform the long division extracting multiple digits at once. Through clever use of the calculator, we can quickly obtain the full decimal representation even though the calculator can only give ten digits at a time.

Let’s now return to where this series began… the decimal representation of using long division. As shown below, the repeating block has length

, which can be found in a few minutes with enough patience. By the end of this post, we’ll consider a modification of ordinary long division that facilitates the computation of really long repeating blocks.

Because we arrived at a repeated remainder, we know that we have found the repeating block. So we can conclude that .

Students are taught long division in elementary school and are so familiar with the procedure that not much thought is given to the logic behind the procedure. The underlying theorem behind long division is typically called the division algorithm. From Wikipedia:

Given two integers

and

, with

, there exist unique integers

and

such that

and $0 \le r < |b|$, where

denotes the absolute value of

.

The number is typically called the quotient, while the number

is called the remainder.

Repeated application of this theorem is the basis for long division. For the example above:

Step 1.

. Dividing by

,

Step 2.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Step 1, we see that

Step 3.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Step 2, we see that

And so on.

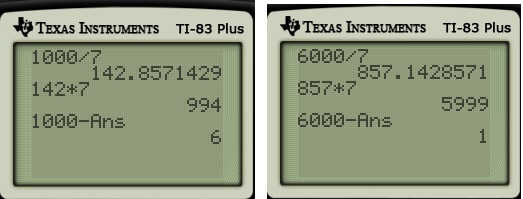

By adding an extra zero and using the division algorithm, the digits in the decimal representation are found one at a time. That said, it is possible (with a calculator) to find multiple digits in a single step by adding extra zeroes. For example:

Alternate Step 1.

. Dividing by

,

Alternate Step 2.

. Dividing by

,

Returning to the end of Alternate Step 1, we see that

So, with these two alternate steps, we arrive at a remainder of and have found the length of the repeating block.

The big catch is that, if or

and

, the appropriate values of

and

have to be found. This can be facilitated with a calculator. The integer part of

and

are the two quotients needed above, and subtraction is used to find the remainders (which must be less than

, of course).

At first blush, it seems silly to use a calculator to find these values of and

when a calculator could have been used to just find the decimal representation of

in the first place. However, the advantage of this method becomes clear when we consider fractions who repeating blocks are longer than 10 digits.

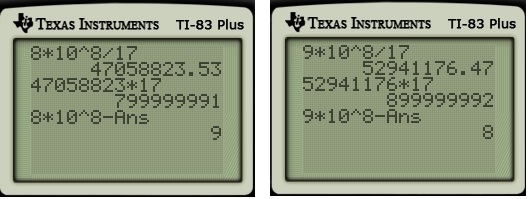

Let’s now return to the question posed at the top of this post: finding the decimal representation of

Let’s now return to the question posed at the top of this post: finding the decimal representation of . As noted in Part 6 of this series, the length of the repeating block must be a factor of

, where

is the Euler toitent function, or the number of integers less than

that are relatively prime with

. Since

is prime, we clearly see that

. So we can conclude that the length of the repeating block is a factor of

, or either

,

,

,

, or

.

Here’s the result of the calculator again:

We clearly see from the calculator that the repeating block doesn’t have a length less than or equal to . By process of elimination, the repeating block must have a length of

digits.

Now we perform the division algorithm to obtain these digits, as before. This can be done in two steps by multiplying by .

So, by the same logic used above, we can conclude that

In other words, through clever use of the calculator, the full decimal representation can be quickly found even if the calculator itself returns only ten digits at a time… and had rounded the final of the repeating block up to

.

A report of the General Accounting office,

A report of the General Accounting office,