In the previous series of posts, I consider how two different definitions of a logarithmic function are actually related to each other. In this series of posts, I consider how two different definitions of the number  are related to each other.

are related to each other.

The number  is usually introduced at two different places in the mathematics curriculum:

is usually introduced at two different places in the mathematics curriculum:

- Algebra II/Precalculus: If

dollars are invested at interest rate

dollars are invested at interest rate  for

for  years with continuous compound interest, then the amount of money after

years with continuous compound interest, then the amount of money after  years is

years is  .

.

- Calculus: The number

is defined to be the number so that the area under the curve

is defined to be the number so that the area under the curve  from

from  to

to  is equal to

is equal to  , so that

, so that

.

.

These two definitions appear to be very, very different. One deals with making money. The other deals with the area under a hyperbola. Amazingly, these two definitions are related to each other. In this series of posts, I’ll discuss the connection between the two.

I should say at the outset that the second definition is usually considered the true definition of  . However, compound interest usually appears earlier in the mathematics curriculum than definite integrals, and so an informal definition of

. However, compound interest usually appears earlier in the mathematics curriculum than definite integrals, and so an informal definition of  is given at that stage of the curriculum.

is given at that stage of the curriculum.

I begin this series of posts with a justification for the compound interest formula  when interest is compounded

when interest is compounded  times a year. My experience is that most math majors are familiar with this formula from their high school experience but have absolutely no idea about why it is true, and so the presentation below fills in a major hole in their preparation to become secondary teachers themselves.

times a year. My experience is that most math majors are familiar with this formula from their high school experience but have absolutely no idea about why it is true, and so the presentation below fills in a major hole in their preparation to become secondary teachers themselves.

In the near future, I’ll discuss how the above formula naturally leads to the formula  when interest is continuously compounded.

when interest is continuously compounded.

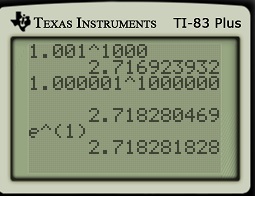

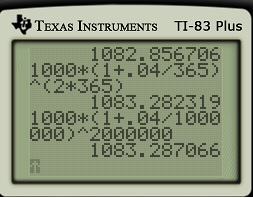

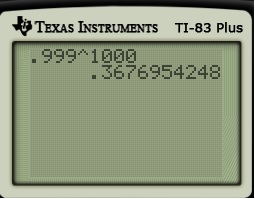

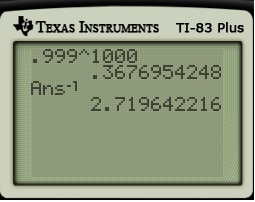

I start with a sequence of numerical examples.

I start with a sequence of numerical examples.

A. Suppose that you invest $1,000 at 4% interest for 2 years. (At the time of this writing, a fixed interest rate of 4% is almost mythological, but let’s leave that aside for the sake of the problem.) How much money do you have if the money is compounded annually? Here are the brute force steps. (To make the presentation less dry, I make sure that my students are volunteering each answer before proceeding to the next step.)

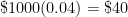

- Amount of interest earned in Year 1 =

.

.

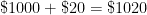

- Total amount of money after Year 1 =

.

.

- Amount of interest earned in Year 2 =

.

.

- Total amount of money earned in Year 2 =

.

.

B. Let’s repeat the above problem, except this time the 4% interest is compounded twice a year. In other words, 2% interest is applied every six months.

- Amount of interest earned in first six months =

.

.

- Total amount of money after first six months =

.

.

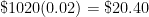

- Amount of interest earned in second six months =

.

.

- Total amount of money earned after second six months =

.

.

At this point, I’ll make a big production about how much work this is, and we’re only halfway done with this calculation! So, I’ll rhetorically ask my class, is there an easier way to do this? Let’s take a look back at the first calculation, adding some observations.

- Amount of interest earned in Year 1 =

.

.

- Total amount of money after Year 1 =

.

.

- Amount of interest earned in Year 2 =

.

.

- Total amount of money earned in Year 2 =

.

.

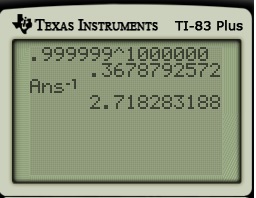

Then I’ll check with a calculator to confirm that  is indeed equal to

is indeed equal to  .

.

Let’s now return to the problem when the 4% interest is compounded twice a year. We’re only halfway through the calculation, but let’s recapitulate what we’ve done so far. Since this is very similar to the above work, students usually can produce the logic very quickly.

- Amount of interest earned in first six months =

.

.

- Total amount of money after first six months =

.

.

- Amount of interest earned in second six months =

.

.

- Total amount of money earned after second six months =

.

.

.

.

At this point, I’ll ask my class what they think how much money will accumulate after two years. Invariably, they guess the correct answer of $latex $1000(1+0.02)^4$. If my class seems to get it, I usually will just accept this as the correct answer without explicitly running through steps 5 through 8 to get to the end of the fourth six weeks.

C. What is the money makes 4% interest compounded four times a year for 2 years? By this point, my students can usually guess the answer:  . The

. The  comes from dividing the 4% into four parts. The 8 comes from the number of compounding periods over 2 years.

comes from dividing the 4% into four parts. The 8 comes from the number of compounding periods over 2 years.

D. By this point, we have pretty much arrived at the compound interest formula:  . The above argument justifies the formula; the actual proof of the formula is very similar to the above numerical examples, and so I don’t use class time to formally prove it.

. The above argument justifies the formula; the actual proof of the formula is very similar to the above numerical examples, and so I don’t use class time to formally prove it.

Tomorrow, I’ll give some pedagogical thoughts about these computations.

be the amount of money on the credit card after

years. Then there are two competing forces on the amount of money that will be owed in the future:

per year.

per year.

is actually a fraction. (In the derivation below, I will be a little sloppy with the arbitrary constant of integration for the sake of simplicity.)

, we use the initial condition

:

years is

and solve for

: