In this series, I’m compiling some of the quips and one-liners that I’ll use with my students to hopefully make my lessons more memorable for them.

Today’s quip is one that I’ll use surprisingly often:

If you ever meet a mathematician at a bar, ask him or her, “What is your favorite application of the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality?”

The point is that the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality arises surprisingly often in the undergraduate mathematics curriculum, and so I make a point to highlight it when I use it. For example, off the top of my head:

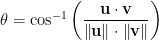

1. In trigonometry, the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality states that

for all vectors  and

and  . Consequently,

. Consequently,

,

,

which means that the angle

is defined. This is the measure of the angle between the two vectors  and

and  .

.

2. In probability and statistics, the standard deviation of a random variable  is defined as

is defined as

![\hbox{SD}(X) = \sqrt{E(X^2) - [E(X)]^2}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Chbox%7BSD%7D%28X%29+%3D+%5Csqrt%7BE%28X%5E2%29+-+%5BE%28X%29%5D%5E2%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

The Cauchy-Schwartz inequality assures that the quantity under the square root is nonnegative, so that the standard deviation is actually defined. Also, the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality can be used to show that  implies that

implies that  is a constant almost surely.

is a constant almost surely.

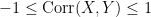

3. Also in probability and statistics, the correlation between two random variables  and

and  must satisfy

must satisfy

.

.

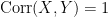

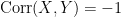

Furthermore, if  , then

, then  for some constants

for some constants  and

and  , where

, where  . On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if  , if

, if  , then

, then  for some constants

for some constants  and

and  , where

, where  .

.

Since I’m a mathematician, I guess my favorite application of the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality appears in my first professional article, where the inequality was used to confirm some new bounds that I derived with my graduate adviser.