In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Irene Ogeto. Her topic, from probability: Venn diagrams.

A2. How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

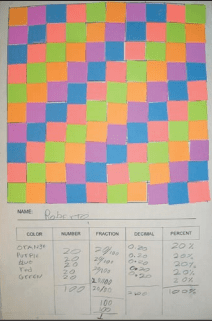

As a warm up activity to a lesson on Venn diagrams, I could set up a model Venn diagram made out of tape on the classroom floor or in the hallway outside of the class. The topic for the activity would be comparing the number of students who prefer to play indoor sports versus the number of students who prefer to play outdoor sports. I would ask the students who prefer to play outdoor sports such as soccer, baseball, football or field hockey to stand in the circle that represents outdoor sports. Then I would ask the students who prefer to play indoor sports such as bowling or table tennis to stand in the other circle. Next, I would ask the students who prefer to play both indoor and outdoor sports such as basketball, volleyball or badminton to stand where the circles intersect. Lastly, I would ask the students who don’t prefer to play any sports to stand outside the two circles.

With this activity we can explore these questions:

- How many students prefer to play indoor sports?

- What is the percentage of students in our class prefer to play indoor sports?

- How many students prefer to play both indoor and outdoor sports?

- What percentage of students in our class prefer play both indoor and outdoor sports?

- What percentage of the students in our class prefer to play sports?

C1. How has this topic appeared in pop culture (movies, TV, current music, video games, etc.)?

Venn diagrams have appeared in children’s TV shows such as Cyberspace. In this episode of Cyberspace which is was aired on PBS in Season 1, the Cyberspace squad uses a Venn diagram to rescue the Lucky Charms. The squad uses the terms “or” and “and” with respect to sets to find the Lucky Charms. Motherboard tells them that the Lucky Charms is both blue and tall. One circle represents the blue bunnies and the other circle represents the bunnies of another color. The area where the two circles intersect represents the area where the tall and blue bunnies are. The squad works together to find the Lucky Charms using applications of Venn diagrams. Venn diagrams can be used to explore possibilities and combinations of things. This video can serve as an introduction to a lesson on Venn diagrams. It enables students to see how math is part of culture, as it is found in television shows.

Episode 112: “Of All the Luck” http://www.pbs.org/parents/cyberchase/episodes/season-1/

D1. What interesting things can you say about the people who contributed to the discovery and/or the development of this topic?

John Venn (1834-1923) the famous mathematician, devised a way to picture sets by creating what is now known as Venn diagrams in 1881. John Venn was born in Hull, New England, United Kingdom. He was a lecturer, president of a college, and a priest for some of the years in his life. Venn wanted to show how different groups of things could be represented visually. John Venn called Venn diagrams Eulerian circles because they were similar to the Euler circles created by Leonhard Euler. While they share similarities, Euler circles and Venn diagrams are different. Venn diagrams are more sophisticated and are used to represent all possible combinations of classes. Euler circles differ in the sense that the circles do not always have to intersect and do not always represent all possible combinations. Some people still refer to Venn diagrams as Eulerian circles to this day and often some people use the two terms interchangeably. Despite the differences, both diagrams are used in math every day.

References:

http://www.venndiagram.net/the-history-behind-the-venn-diagram.html

http://www.mathresources.com/products/mathresource/maa/venn_diagram.html

http://www.pbs.org/parents/cyberchase/episodes/season-1/