A colleague placed the following problem on an exam, expecting the following solution:

However, one student produced the following solution (see yesterday’s post for details):

As he couldn’t find a mistake in the student’s work, he assumed that the two expressions were equivalent. Indeed, he differentiated the student’s work to make sure it was right. But he couldn’t immediately see, using elementary reasoning, why they were equivalent. So he walked across the hall to my office to ask me if I could help.

Here’s how I showed they are equivalent.

Let and

. Then

.

Let’s evaluate the four expressions on the right-hand side.

First, is clearly equal to

.

Second, , so that

.

Third, to evaluate $\cos \alpha$, I’ll use the identity :

Fourth, . Using the above identity again, we find

Combining the above, we find

for some integer

Also, since and

, we see that

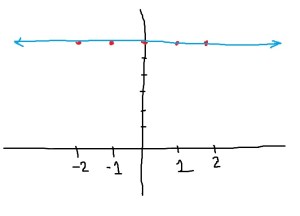

. (From its definition, $\beta$ is the arcsine of a positive number and therefore must be nonnegative.) Therefore,

.

In other words,

and

differ by a constant, thus showing that the two antiderivatives are equivalent.