I’m in the middle of a series of posts concerning the elementary operation of computing a square root. This is such an elementary operation because nearly every calculator has a button, and so students today are accustomed to quickly getting an answer without giving much thought to (1) what the answer means or (2) what magic the calculator uses to find square roots.

I like to show my future secondary teachers a brief history on this topic… partially to deepen their knowledge about what they likely think is a simple concept, but also to give them a little appreciation for their elders. Indeed, when I show this method to today’s college students, they are absolutely mystified that a square root can be extracted by hand, without the aid of a calculator.

To begin, let’s again go back to a time before the advent of pocket calculators… say, ancient Rome. (I personally love using Back to the Future for the pedagogical purpose of simulating time travel, but I already used that in the previous post.)

How did previous generations figure out without a calculator? In the previous post, I introduced a trapping method that directly used the definition of

for obtaining one digit at a time. Here’s a second trapping method that’s significantly more efficient. As we’ll see, this second method works because of base-10 arithmetic and a very clever use of Algebra I. My understanding is that this procedure was a standard topic in the mathematical training of children as little as 50 years ago.

Personally, I was taught this method when I was maybe 10 or 11 years old by my math teacher; I don’t doubt that she had to learn to extract square roots by hand when she was a student. Of course, this trapping method fell out of pedagogical favor with the advent of cheap pocket calculators.

I’ll illustrate this method again with . After illustrating the method, I’ll discuss how it works using Algebra I.

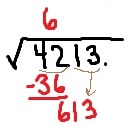

1. To begin, we start from the decimal point and group digits in block of two. (If the number had been , then the

would have been in a group by itself.) I start with the

. What perfect square is closest to

without going over? Clearly, the answer is

. So, mimicking the algorithm for long division:

- We’ll place a

over the

, signifying that the answer is in the

s.

- We’ll subtract

from

, for an answer of

.

2. On the next step, we’ll do a couple of things that are different from ordinary long division:

2. On the next step, we’ll do a couple of things that are different from ordinary long division:

- We’ll bring down the next two digits. So we’ll work with

.

- We’ll double the number currently on top and place the result to the side. In our case $6 \times 2 = 12$.

- We’ll place a small ___ after the

and under the

.

- The basic question is: I need

–something times the same something to be as close to

as possible without going over. I like calling this The Price Is Right problem, since so many games on that game show involve guessing a price without going over the actual price. For example…

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too big

- Based on the above work, the next digit is

. We place the

over the next block of digits and subtract

from

. So we will work with

on the next step.

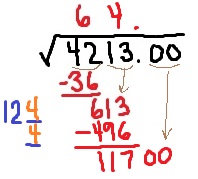

3. On the next step, we’ll do a couple of things that are different from ordinary long division:

3. On the next step, we’ll do a couple of things that are different from ordinary long division:

- We’ll bring down the next two digits. On this step, the next two digits are the first two zeroes after the decimal point. So we’ll work with

.

- We’ll double the number currently on top and place the result to the side. In our case $64 \times 2 = 128$.

- We’ll place a small ___ after the

and under the

.

- The basic question is: I need

–something times the same something to be as close to

as possible without going over. For example…

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: too small

: still too small

- Based on the above work, the next digit is

. We place the

over the next block of digits and subtract

from

. So we will work with

on the next step.

Then, to quote The King and I, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. Each step extracts an extra digit of the square root. With a little practice, one gets better at guessing the correct value of .

A personal story: when I was a teenager and too cheap to buy a magazine, I would extract square roots to kill time while waiting in the airport for a flight to start boarding. My parents hated missing flights, so I was always at the gate with plenty of time to spare… and I could extract about 20 digits of while waiting for the boarding announcement.

So why does this algorithm work? I offer a thought bubble if you’d like to think about before I give the answer.

P.S. In case anyone complains, the people of ancient Rome could not have performed this algorithm since they used Roman numerals and not a base 10 decimal system.

To see why this works, let’s consider the first two steps of finding . Clearly, the answer lies between

and

somewhere (that was Step 1). So the basic problem is to solve for

if

,

where is the excess amount over

. Squaring, we obtain

,

or

,

or

Notice that the right-hand side is , which was obtained at the start of Step 2. The left-hand side has the form

–something times the same something, which was the key part of completing Step 2. So the value of

that gets

as close to

as possible (without going over) will be the next digit in the decimal representation of

.

The logic for the remaining digits is similar.

I should mention that third roots, fourth roots, etc. can (in principle) be found using algebra to find excess amounts. However, it’s quite a bit more work for these higher roots. For example, to find the cube root of , we immediately see that

, so that the answer lies between

and

. To find the excess amount over 10, we need to solve

,

which reduces to

.

So we then try out values of so that the left-hand side gets as close to

as possible without going over.

In closing, in honor of this method, here’s a great compilation of clips from The Price Is Right when the contestant guessed a price that was quite close to the actual price without going over.