In this series of posts, I consider how two different definitions of the number are related to each other. The number

is usually introduced at two different places in the mathematics curriculum:

- Algebra II/Precalculus: If

dollars are invested at interest rate

for

years with continuous compound interest, then the amount of money after

years is

.

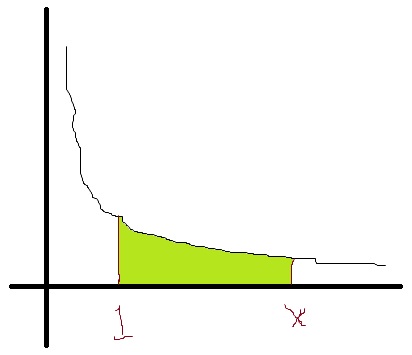

- Calculus: The number

is defined to be the number so that the area under the curve

from

to

is equal to

, so that

.

These two definitions appear to be very, very different. One deals with making money. The other deals with the area under a hyperbola. Amazingly, these two definitions are related to each other. In this series of posts, I’ll discuss the connection between the two.

I should say at the outset that the second definition is usually considered the true definition of . However, compound interest usually appears earlier in the mathematics curriculum than definite integrals, and so an informal definition of

is given at that stage of the curriculum.

At this point in the exposition, I have justified the formula

At this point in the exposition, I have justified the formula for computing the value of an investment when interest is compounded

times a year. In tomorrow’s post, I’ll discuss how the above formula naturally leads to the formula

when interest is continuously compounded.

The bridge between these two formulas is considering increasing values of . So far in the presentation, we have considered an investment of $1000 making 4% interest for 2 years. In the first post of this series, we made the following computations:

1. If interest is compounded annually (), then

.

2. If interest i compounded semiannually (), then

.

3. If interest is compounded quarterly (), then

.

So I ask my class, “What happens to the final amount as interest is compounded more frequently?” They easily observe that the final amount increases somewhat. A natural question, then, is to find how much it can increase. So let’s make the compounding more frequent and let’s see what happens.

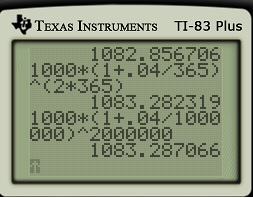

4. Daily: (). Then

.

5. About twice a minute (): Then

.

Of course, I perform all of these calculations in real time on a calculator so that students can follow along:

Students quickly observe that the final amount continues to increase as increases. However, the final amount appears to be leveling off… we can’t make the final amount arbitrarily large just by compounding the interest more frequently.

This provides a natural bridge to continuous compound interest, the topic of tomorrow’s post.

I’ll also note parenthetically that this is why financial institutions are required to disclose the annual percentage rate of a loan (among other things). Otherwise, banks could get away with declaring “Only 2% interest monthly!!” That sounds like 24% annual interest. However, , and so the annual percentage rate would really be 26.824%.