This mathematical trick was not part of my Pi Day magic show but probably should have been… I’ve performed this for my Precalculus classes in the past but flat forgot about it when organizing my Pi Day show. The next time I perform a magic show, I’ll do this one right after the 1089 trick. (I think I learned this trick from a Martin Gardner book when I was young, but I’m not sure about that.)

Here’s a description of the trick. I give my audience a deck of cards and ask them to select six cards between ace and nine (in other words, no tens, jacks, queens, or kings). The card are placed face up, side by side.

After about 5-10 seconds, I secretly write a pull out a card from the deck and place it face down above the others.

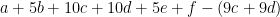

I then announce that we’re going to some addition together… with the understanding that I’ll never write down a number larger than 9. For example, the 4 and 6 of spades are next to each other. Obviously,  , but my rule is that I’m going to write down a number larger than 9. So I’ll subtract 9 whenever necessary:

, but my rule is that I’m going to write down a number larger than 9. So I’ll subtract 9 whenever necessary:  . Since 1 corresponds to ace, I place an ace about the 4 and 6 of spades.

. Since 1 corresponds to ace, I place an ace about the 4 and 6 of spades.

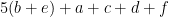

Continuing in this way (and having the audience participate in the arithmetic so that this doesn’t get boring), I eventually get to this position:

Finally, I add the two cards at the top (and, in this case, subtract 9) to get  , and I dramatically turn over the last card to reveal a 6.

, and I dramatically turn over the last card to reveal a 6.

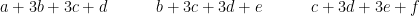

How does this trick work? This is an exercise in modular arithmetic (see also Wikipedia). Suppose that the six cards are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Forgetting for now about subtracting by 9, here’s how the triangle unfolds (turning the triangle upside down):

. Forgetting for now about subtracting by 9, here’s how the triangle unfolds (turning the triangle upside down):

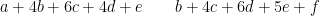

Therefore, the top card will simply be  minus a multiple of 9.

minus a multiple of 9.

That’s a pretty big calculation for the magician to do on the spot. Fortunately,  is also a multiple of 9, and so the top card will be

is also a multiple of 9, and so the top card will be

minus a multiple of 9, or

minus a multiple of 9, or

minus a multiple of 9.

minus a multiple of 9.

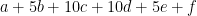

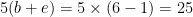

For the case at hand,  and

and  , so

, so  . That’s still a big number to keep straight when performing the trick. However, since I’m going to be subtracting 9’s anyway, I can do this faster by replacing the 8 by

. That’s still a big number to keep straight when performing the trick. However, since I’m going to be subtracting 9’s anyway, I can do this faster by replacing the 8 by  . So, for the purposes of the trick,

. So, for the purposes of the trick,  , and I subtract

, and I subtract  to get

to get  .

.

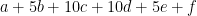

I now add the rest of the cards, subtracting 9 as I go along. For this example, I’d add the 2 first to get 9, which is 0 after subtracting another 9. I then add the remaining cards of 4, 3, and 8 (remembering that the 8 is basically  , yielding

, yielding  . So the top card has to be 6.

. So the top card has to be 6.

The key point of this calculation is to subtract 9 whenever possible to keep the numbers small, making it easier to do in your head when performing the trick.

is not an element of a number system that has the usual definition of inequality.