In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Brittany Tripp. Her topic, from Precalculus: finding the domain and range of a function.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

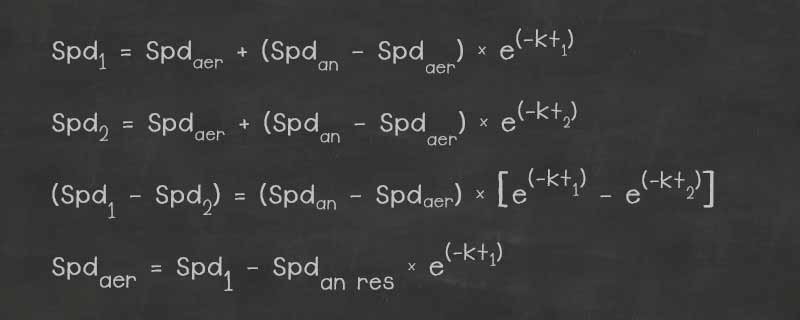

One of my favorite games growing up was Memory. For those who haven’t played, the objective of the game is to find matching cards, but the cards are face down so you take turns flipping over two cards and have to remember where the cards are so when you find the match you can flip both of the matching cards. To win the game you have to have the most matches. I think creating an activity like this, that involves finding domain and range, would be a really fun way to get students’ engaged and excited about the topic. You could place the students in pairs or small groups and give each student a worksheet that has a mixture of functions and graphs of functions. Then the cards that are laying face down would contain various different domains and ranges. In order to get a match you have to find the card that has the correct domain and the card that has the correct range for whatever function or graph you are looking at. You could increase the level of difficulty by having functions, graphs, domains, and ranges on both the worksheet and the cards. This would require the students to not only be able to look at a graph of a function or a function and find the domain and range, but also look at a domain and range and be able to identify the function or graph that fits for that domain and range.

These pictures provide an example of something similar that you could do. I would probably adjust this a little bit so that the domain and ranges aren’t always together and provide actual equations of functions that the students’ must work with as well.

How can this topic be used in your student’s future courses in mathematics or science?

Finding the domain and range of a function is used and expanded on in a variety of ways after precalculus. For instance, one way the domain and range is used in calculus is when evaluating limits. An example is the limit of x-1 as x goes to 1 is equal to zero, because when looking at the graph when the domain, x, is equal to 1 the range, y, is equal to zero. Finding domain and range is something that is applied to a variety of different type of functions in later courses, like when looking at trigonometric functions and the graphs of trigonometric functions. You look at what happens to the domain of a function when you take the derivative in calculus and later courses. You work with the domain and range of different equations and graphs in Multivariable calculus when you are switching to different types of coordinates such as polar, rectangular, and spherical. There are also multiple different science courses that use this topic in some way, one of those being physics. Physics involves a lot of math topics discussed above.

How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

I found a website called Larson Precalculus that technically is targeted toward specific Precalculus books, but exploring this website a little bit I found that is would be a super beneficial tool to use in a classroom. This website has a variety of different tools and resources that students could use. It has book solutions which if you weren’t actually using that specific textbook could be a really helpful tool for students. This would provide them with problems and solutions that are not exactly the same to what they are doing, but similar enough that they could use them as examples to learn from. This website also includes instructional videos that explain in depth how to tackle different Precalculus topics including finding domain and range. There are interactive exercises which would give the students ample opportunities to practice finding the domain and range of graphs and functions. There are data downloads that give the students to ability to download real data in a spreadsheet that they can use to solve problems. These are only a few of the different resources this website provides to students. There are also chapter projects, pre and post tests, math graphs, and additional lessons. All of these things could be used to engage students and help advance and deepen their understanding of finding domain and range. The only downfall is that it is not a free resource. It is something that would have to be purchased if you chose to use it for your classes.

References:

http://esbailey.cuipblogs.net/files/2015/09/Domain-Range-Matching.pdf