In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

We previously showed that if the motion of a planet around the Sun is expressed in polar coordinates , with the Sun at the origin, then under Newtonian mechanics (i.e., without general relativity) the motion of the planet follows the differential equation

,

where and

is a certain constant. We will also impose the initial condition that the planet is at perihelion (i.e., is closest to the sun), at a distance of

, when

. This means that

obtains its maximum value of

when

. This leads to the two initial conditions

;

the second equation arises since has a local extremum at

.

In the next few posts, we’ll discuss the solution of this initial-value problem. Today’s post would be appropriate for calculus students, which is confirming that

solves this initial-value problem, where . Since

is the reciprocal of

, we infer that

.

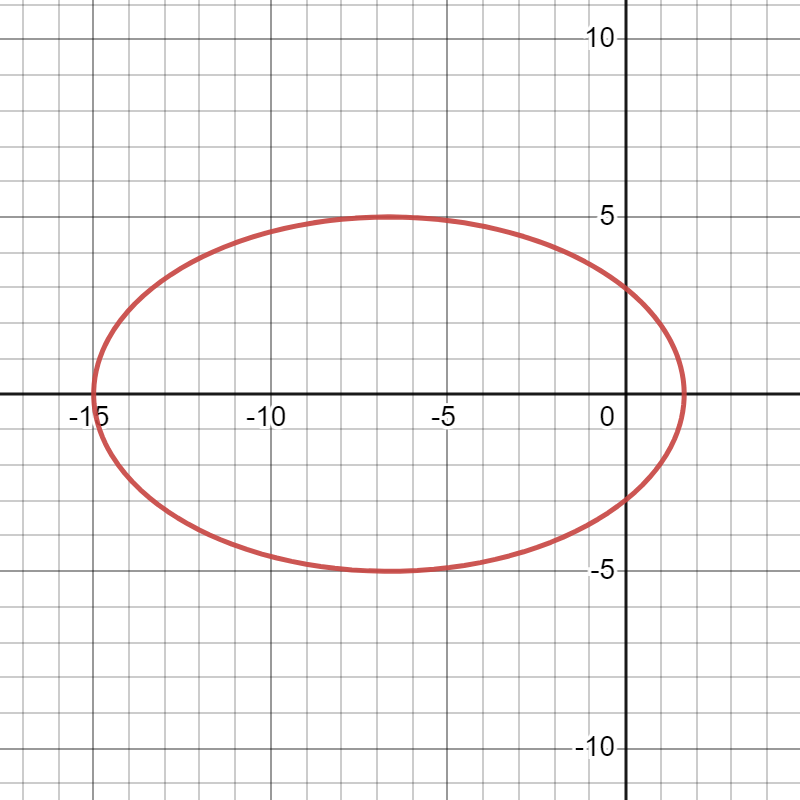

As we’ve already seen in this series, this means that the orbit of the planet is a conic section — either a circle, ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola. Since the orbit of a planet is stable and is extremely unlikely, this means that the planet orbits the Sun in an ellipse, with the Sun at one focus of the ellipse.

So, for a calculus student to verify that planets move in ellipses, one must check that

is a solution of the initial-value problem

,

,

.

The second line is easy to check:

.

The third line is also easy to check:

.

To check the first line, we first find :

,

so that

,

thus confirming that solves the initial-value problem.

While the above calculations are well within the grasp of a good Calculus I student, I’ll be the first to admit that this solution is less than satisfying. We just mysteriously proposed a solution, seemingly out of thin air, and confirmed that it worked. In the next post, I’ll proposed a way that calculus students can be led to guess this solution. Then, we talk about finding the solution of this nonhomogeneous initial-value problem using standard techniques from differential equations.