In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Michelle McKay. Her topic, from Algebra I: solving for unknown parts of triangles and rectangles.

A. How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

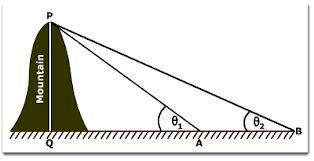

There are several different ideas that immediately come to mind on how to center a lesson around solving for unknown parts of rectangles and triangles. I would like to focus on and describe one. For this particular lesson, the student will start by making a prediction of which side(s) of a shape (triangle or rectangle) has the greatest length. Then, with a partner, they will use rulers and a handout to record the dimensions of both shapes. On the handout, they will work to fill out the chart provided. Then, we will reconvene as a class and talk about the discoveries made. For rectangles, I would ask first about what we found to be consistent for every rectangle. Using what we know, how we could find or solve for the length of one side if we only had certain parts of information? Similarly for triangles, I would begin by asking how each side differed from one another. Did the general shapes of the triangles make a difference? What was special about the right triangles? After these questions, I would introduce Pythagorean’s Theorem and have them solve for the side of triangles without rulers, then follow up with using rulers to verify their information.

D. What interesting things can you say about the people who contributed to the discovery and/or the development of this idea?

Pythagoras of Samos: During Pythagoras’ time, math was considered to be a mixture of both religious and scientific beliefs and was often associated with secret societies and only those of very high social standing. As Pythagoras was one of the more influential mathematicians of his time, most details of his life were kept secret until centuries after his death, leaving very little reliable information to be pieced together in form of a biography. It is generally accepted that he was born on the island of Samos, which is now incorporated into the country of Greece. Little is known about his childhood, but most agree that he was very well educated and was acquainted with geometry before he traveled to Egypt. He was known to be almost sacrosanct and divine to those alive during his time and even a few well after his death. He founded a religious, and simultaneously mathematical, movement called Pythagoreanism, which consisted of two schools of thought: the “learners” and the “listeners”.

D. What are the contributions of various cultures to this topic?

|

Time Period |

Civilization |

Contribution |

|

Earliest known references: 23rd Century B.C. |

Babylonians |

– Had rules for generating Pythagorean triples.

– Comprehended the relationship of a right triangle’s sides. – Discovered the relationship of

|

|

500 – 200 B.C. |

Chinese |

– Gives a statement and geometrical demonstration of the Pythagorean Theorem (possibly before Pythagoras’ time).

|

|

570 – 495 B.C. |

Greek |

– Golden rectangles were very vaguely referenced by Plato.

– Euclid wrote a clear definition of what a rectangle is. – Pythagoras discovered a relationship between the sides of right triangles.

|

|

Earliest known references:

|

Indian |

– Pythagorean Theorem was utilized in forming the proper dimensions for religious altars. |

It is very hard to for historians to pinpoint with exact certainty which civilization was the first to discover what we know now as the Pythagorean Theorem. Many of the civilizations listed above existed during the same time period, but were geographically located on opposite ends of the map. Also due to loss of information from translations, damaged or completely destroyed texts, these dates and the authenticity of certain contributions are still debated to this day.

Sources