In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Michelle McKay. Her topic, from Precalculus: verifying trigonometric identities.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Engaging students with trigonometric identities may seem daunting, but I believe the key to success for this unit lies within allowing students to make the discovery of the identities themselves.

For this particular activity, I will focus on some trigonometric identities that can be derived using the Pythagorean Theorem. Before beginning this activity, students must already know about the basic trig functions (sine, cosine, and tangent) along with their corresponding reciprocals (cosecant, secant, and cotangent).

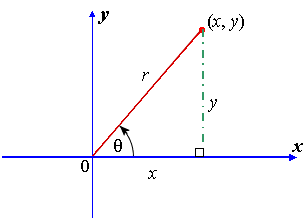

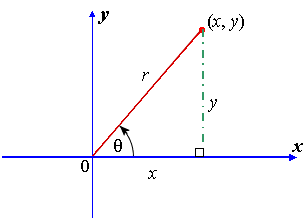

Using this diagram (or a similar one), have students write out the relationship between all sides using the Pythagorean Theorem.

Students should all come to the conclusion of: x2 + y2 = r2.

For higher leveled students, you may want to remind them of the adage SohCahToa, with emphasis on sine and cosine for this next part. You might ask, “How can we rearrange the above equation into something remotely similar to a trigonometric function?”

Ultimately, we want students to divide each side by r2. This will give us:

Again, SohCahToa. Students, perhaps with some leading questions, should see that we can substitute sine and cosine functions into the above equation, giving us the identity:

cos2θ + sin2θ = 1

From this newly derived identity, students can then go on to find tan2θ + 1 = sec2θand then 1 + cot2θ = csc2θ.

How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

For engaging the students and encouraging them to play around with identities, I find the Trigonometric Identities Solver by Symbolab to be a fabulous technological supplement. Students can enter in identities that they may need more help understanding and this website will state whether the identity is true or not, and then provide detailed steps on how to derive the identity.

A rather fun activity that may utilize this site is to challenge the students to come up with their own elaborate trigonometric identity.

Another online tool students can explore is the interactive graph from http://www.intmath.com. In fact, students could also use this right after they derive the identities from the earlier activity. This site does a wonderful job at providing a visual representation of the trigonometric functions’ relationships to one another. It also allows the students to explore the functions using concrete numbers, rather than the general Ө. Although this site only shows the cos2θ + sin2θ = 1identity in action, it would not be difficult for students to plug in the data from this graph to numerically verify the other identities.

What are the contributions of various cultures to this topic?

The beginning of trigonometry began with the intention of keeping track of time and the quickly expanding interest in the study of astronomy. As each civilization inherited old discoveries from their predecessors, they added more to the field of trigonometry to better explain the world around them. The below table is a very brief compilation of some defining moments in trigonometry’s history. It is by no means complete, but was created with the intention to capture the essence of each civilization’s biggest contributions.

| Civilization |

People of Interest |

Contributions |

| Egyptians |

|

– Earliest ideas of angles.- The Egyptian seked was the cotangent of an angle at the base of a building. |

| Babylonians |

|

– Division of the circle into 360 degrees.- Detailed records of moving celestial bodies (which, when mapped out, resembled a sine or cosine curve).- May have had the first table of secants. |

| Greek |

- Aristarchus

- Menelaus

- Hippocharus

- Ptolemy

|

– Chords.- Trigonometric proofs presented in a geometric way.- First widely recognized trigonometric table: Corresponding values of arcs and chords.- Equivalent of the half-angle formula. |

| Indian |

- Aryabhata

- Bhaskara I

- Bhaskara II

- Brahmagupta

- Madhava

|

– Sine and cosine series.- Formula for the sine of an acute angle.- Spherical trigonometry.- Defined modern sine, cosine, versine, and inverse sine. |

| Islamic |

- Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī

- Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī

- Abū al-Wafā’ al-Būzjānī

|

– – First accurate sine and cosine tables.- – First table for tangent values.- – Discovery of reciprocal functions (secant and cosecant).- – Law of Sines for spherical trigonometry.- – Angle addition in trigonometric functions. |

| Germans |

|

– “Modern trigonometry” was born by defining trigonometry functions as ratios rather than lengths of lines. |

It is interesting to note that while the Chinese were making many advances in other fields of mathematics, there was not a large appreciation for trigonometry until long after they approached the study and other civilizations had made significant contributions.

Sources

- http://www.intmath.com/analytic-trigonometry/1-trigonometric-identities.php

- http://www.intmath.com/analytic-trigonometry/trig-ratios-interactive.php

- http://symbolab.com/solver

- http://www.trigonometry-help.net/history-of-trigonometry.php

- http://nrich.maths.org/6843&part=

- http://www.scribd.com/doc/33216837/The-History-of-Trigonometry-and-of-Trigonometric-Functions-May-Span-Nearly-4

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/605281/trigonometry/12231/History-of-trigonometry

,

). In these formulas,

and

. (Also,

is a certain angle that is now irrelevant at this point in the calculation).

where the denominator is equal to 0, and then determining which of those values lie inside of the closed contour.

and/or

.

. Clearly, the numbers

,

, and

are the lengths of three sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse

. So, since the hypotenuse is the longest side,

.

,

, so that

does lie inside of the contour

.

is easier to handle:

.

lies outside of the contour, this root is not important for the purposes of computing the above contour integral.