Tag: polynomial

Proving theorems and special cases (Part 16): An old homework problem

In a recent class with my future secondary math teachers, we had a fascinating discussion concerning how a teacher should respond to the following question from a student:

Is it ever possible to prove a statement or theorem by proving a special case of the statement or theorem?

Usually, the answer is no. In this series of posts, we’ve seen that a conjecture could be true for the first 40 cases or even the first cases yet not always be true. We’ve also explored the computational evidence for various unsolved problems in mathematics, noting that even this very strong computational evidence, by itself, does not provide a proof for all possible cases.

However, there are plenty of examples in mathematics where it is possible to prove a theorem by first proving a special case of the theorem. For the remainder of this series, I’d like to list, in no particular order, some common theorems used in secondary mathematics which are typically proved by first proving a special case.

The following problem appeared on a homework assignment of mine about 30 years ago when I was taking Honors Calculus out of Apostol’s book. I still remember trying to prove this theorem (at the time, very unsuccessfully) like it was yesterday.

Theorem. If is a continuous function so that

, then

for some constant

.

Proof. The proof mirrors that of the uniqueness of the logarithm function, slowly proving special cases to eventually prove the theorem for all real numbers .

Case 1. . If we set

and

, then

Case 2. . If

is a positive integer, then

.

(Technically, this should be proven by induction, but I’ll skip that for brevity.) If we let , then

.

Case 3. . If

is a negative integer, let

, where

is a positive integer. Then

Case 4. . If

is a rational number, then write

, where

and

are integers and

is a positive integer. We’ll use the fact that

, where the sum is repeated

times.

Case 5. . If

is a real number, then let

be a sequence of rational numbers that converges to

, so that

Then, since is continuous,

QED

Random Thought #1: The continuity of the function was only used in Case 5 of the above proof. I’m nearly certain that there’s a pathological discontinuous function that satisfies

which is not the function

. However, I don’t know what that function might be.

Random Thought #2: For what it’s worth, this same idea can be used to solve the following problem that was posed during UNT’s Problem of the Month competition in January 2015. I won’t solve the problem here so that my readers can have the fun of trying to solve it for themselves.

Problem. Determine all nonnegative continuous functions that satisfy

.

Engaging students: Completing the square

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Tracy Leeper. Her topic, from Algebra: completing the square.

What interesting things can you say about the people who contributed to the discovery and/or the development of this topic?

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi wrote a book called al-jabr in approximately 825 A.D. He was in Babylon and he worked as a scholar at the House of Wisdom. Al-Khwarizmi had already mastered Euclid’s Elements, which is the foundation for Geometry. So in his book he posed the challenge “What must be the square which, when increased by ten of its own roots; amounts to 39?” or in other words: how to solve he turned to geometry and drew a picture to figure out the answer. By doing so, al-Khwarizmi found out how to solve equations by completing the square. He also included instructions on how he solved the problem in words. His book al-jabr become the foundation for our modern day algebra. The Arabic word al-jabr was translated into Latin to give us algebra, and our word for algorithm came from al-Khwarizmi, if you can believe it. Later on, his work was used by other Arab and Renaissance Italian mathematicians to “complete the cube” for solving cubic equations.

How does this topic extend what your students should have learned in previous courses?

In previous courses my students should have already been introduced to prime factorization, the quadratic formula, parabolas, coordinates graphs and other similar topics. Completing the square is another way for students to find the roots of a quadratic equation. The first way taught is by using nice numbers that will factor easily. Then the math progresses to using the quadratic equation for the numbers that don’t factor easily. Completing the square is just another way to solve a quadratic that does not easily factor. Some students prefer to go straight to the quadratic equation, whereas other students will favor completing the square after they learn how to do it. It gives the students another “tool” for their toolbox on how to solve equations, and will enable them to solve equations that previously were unsolvable, such as the quadratic . By giving students a variety of ways to solve a problem, they can pick whichever way they are most comfortable with, which in turn will boost their confidence in their ability to learn math.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Usually the simplest way to learn something is to see something concrete of what you are trying to do. For completing the square, I can give the students the procedure to follow, but they probably won’t be able to fully understand why it works. In order to help them visualize it, I would use algebra tiles. One long tile is equal to x, since its length is x and its width is 1. The square is equal to since the length and the width are both equal to x. However, when you try to add to the square by a factor of x, you end up having a corner missing. This is the part that is missing from the initial equation. Then the students see that you don’t have a complete square, but by adding the same amount to both parts, we can get a complete square that can then be factored. Like so…

References:

http://bulldog2.redlands.edu/fac/beery/math115/m115_activ_complsq.htm

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JXrj5Dtgpss

Engaging students: Graphing parabolas

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Tiffany Wilhoit. Her topic, from Algebra: graphing parabolas.

How did people’s conception of this topic change over time?

The parabola has been around for a long time! Menaechmus (380 BC-320 BC) was likely the first person to have found the parabola. Therefore, the parabola has been around since the ancient Greek times. However, it wasn’t until around a century later that Apollonius gave the parabola its name. Pappus (290-350) is the mathematician who discovered the focus and directrix of the parabola, and their given relation. One of the most famous mathematicians to contribute to the study of parabolas was Galileo. He determined that objects falling due to gravity fall in parabolic pathways, since gravity has a constant acceleration. Later, in the 17th century, many mathematicians studied properties of the parabola. Gregory and Newton discovered that parabolas cause rays of light to meet at a focus. While Newton opted out of using parabolic mirrors for his first telescope, most modern reflecting telescopes use them. Mathematicians have been studying parabolas for thousands of years, and have discovered many interesting properties of the parabola.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

A fun activity to set up for your students will include several boxes and balls, for a smaller set up, you can use solo cups and ping pong balls. Divide the class into groups, and give each group a set of boxes and balls. First, have the students set up a tower(s) with the boxes. The students will now attempt to knock the boxes down using the balls. The students can map out the parabolic curve showing the path they want to take. By changing the distance from the student throwing the ball and the boxes, the students will be able to see how the curve changes. If students have the tendency to throw the ball straight instead of in the shape of a parabola, have a member of the group stand between the thrower and the boxes. This will force the ball to be thrown over the student’s head, resulting in the parabolic curve. The students can also see what happens to the curve depending on where the student stands between the thrower and boxes. In order for the students to make a positive parabolic curve, have them throw the ball underhanded. This activity will engage the students by getting them involved and active, plus they will have some fun too! (To start off with, you can show the video from part E1, since the students are playing a real life version of Angry Birds!)

How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

A great video to show students before studying parabolas can be found on YouTube:

The video uses the popular game Angry Birds to introduce parabolic graphs. First, the video shows the bird flying a parabolic path, but the bird misses the pig. The video goes on to explain why the pig can’t be hit. It does a good job of explaining what a parabola is, why the first parabolic curve would not allow the bird to hit the pig, and how to change the curve to line up the path of the bird to the pig. This video would be interesting to the students, because a majority of the class (if not all) will know the game, and most have played the game! The video goes even further by encouraging students to look for parabolas in their lives. It even gives other examples such as arches and basketball. This will get the students thinking about parabolas outside of the classroom. (This video would be perfect to show before the students try their own version of Angry Birds discussed in part A2)

Resources:

Youtube.com/watch?v=bsYLPIXI7VQ

Parabolaonline.tripod.com/history.html

http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Curves/Parabola.html

Engaging students: Factoring quadratic polynomials

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Kristin Ambrose. Her topic, from Algebra: factoring quadratic polynomials.

In previous courses, students would have learned how to solve one-variable linear equations. These kinds of equations would involve variables to the power of one. Quadratic equations extend from this since they add a variable to the equation that is to the power of two. Since students learned how to solve linear equations, they may be curious as to how they can solve quadratic equations that extend from this. Factoring is a way for students to solve these kinds of equations.

Also, in previous courses students would have learned about the ‘factors’ of a number. When talking about numbers, the factors are the numbers you multiply to get another number. For example the positive factors of six are one and six, and two and three. Factoring quadratic polynomials follows this logic, except instead finding the factors of a number, students are finding the factors of an expression. For example, the factors of the expression are (x+3) and (x+1). Just like how when we multiply two times three we get six, when we multiply (x+3) times (x+1) we get the expression

.

How has this topic appeared in pop culture (movies, TV, current music, video games, etc.)?

There is a popular video game called Angry Birds in which the user launches birds to try and knock down structures built by pigs. This game relates to factoring quadratics because if we were to plot the trajectory of the birds being launched on a graph, the result would be a parabola, in other words the graph of a quadratic function. Factoring quadratic polynomials is a way to find the solutions of a quadratic, and the solutions are where the parabola crosses the x-axis. In Angry Birds, we could set our x-axis to be the ground, and our solutions would correspond with where on the ground the bird would land, if nothing were to block its path. If students were given the quadratic equation for the parabola corresponding with the bird’s trajectory, students would be able to factor the equation to solve for where on the ground the bird would land.

What are the contributions of various cultures to this topic?

Indian and Islamic cultures are two major cultures that have contributed to the topic of factoring quadratic polynomials. In Islamic culture, Al-Khwarizmi contributed to this topic by creating a way to solve quadratic equations by reducing the equations to one of six forms, which were then solvable. He described these forms in terms of squares, roots, and numbers, much like the terms we use today when factoring quadratic polynomials. The ‘squares’ related to what would today be our ‘x2’ term, the ‘roots’ related to the ‘x’ term, and the ‘numbers’ to the ‘c’ constant term. One of the forms he described was “squares and roots equal numbers,” in modern terms, “ax2 + bx = c.” Today, we factor quadratic polynomials of the form “ax2 + bx + c” which is similar to the form Al-Khwarizmi described. (Islamic Mathematics – Al-Khwarizmi)

In Indian culture, Brahmagupta contributed to the concept of factoring quadratics by introducing the idea that a number could be negative. This was significant because it meant a number like 9 could be factored into 32 or (-3)2. Since a number could have a negative factor, it followed that quadratic equations could have two possible solutions, since one solution could be negative. Factoring quadratic polynomials like we do today would be impossible without the knowledge that quadratic expressions can have two solutions. (Indian Mathematics – Brahmagupta)

References:

“Islamic Mathematics – Al-Khwarizmi.” The Story of Mathematics. 2010. Web. 17 Sept. 2014. <http://www.storyofmathematics.com/islamic_alkhwarizmi.html>.

“Indian Mathematics – Brahmagupta.” The Story of Mathematics. 2010. Web. 17 Sept. 2014. <http://www.storyofmathematics.com/indian_brahmagupta.html>.

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra: A Visual Approach

A former student forwarded to me the following article concerning a visual way of understanding the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, which dictates that every nonconstant polynomial has at least one complex root: http://www.cs.amherst.edu/~djv/FTAp.pdf. The paper uses a very clever idea, from the opening paragraphs:

[I]f we want to use pictures to display the behavior of polynomials defined on the complex numbers, we are immediately faced with a difficulty: the complex numbers are two-dimensional, so it appears that a graph of a complex-valued function on the complex numbers will require four dimensions. Our solution to this problem will be to use color to represent some dimensions. We begin by assigning a color to every number in the complex plane… so a complex number can be uniquely specified by giving its color.

We can now use this color scheme to draw a picture of a function

as follows: we simply color each point

in the complex plane with the color corresponding to the value of

. From such a picture, we can read off the value of

… by determining the color of the point z in the picture…

The article is engagingly written; I recommend it highly.

My “history” of solving cubic, quartic and quintic equations

When I teach Algebra II or Precalculus (or train my future high school teachers to teach these subjects), we eventually land on the Rational Root Test and Descartes’ Rule of Signs as an aid for finding the roots of cubic equations or higher. Before I get too deep into this subject, however, I like to give a 10-15 minute pseudohistory about the discovery of how polynomial equations can be solved. Historians of mathematics will certain take issue with some of this “history.” However, the main purpose of the story is not complete accuracy but engaging students with the history of mathematics. I think the story I tell engages students while remaining reasonably accurate… and I always refer students to various resources if they want to get the real history.

To begin, I write down the easiest two equations to solve (in all cases, :

and

These are pretty easy to solve, with solutions well known to students:

and

In other words, there are formulas that you can just stick in the coefficients and get the answer out without thinking too hard. Sure, there are alternate ways of solving for that could be easier, like factoring, but the worst-case scenario is just plugging into the formula.

These formulas were known to Babylonian mathematicians around 2000 B.C. (When I teach this in class, I write the date, and all other dates and discoverers, next to the equations for dramatic pedagogical effect.) Though not written in these modern terms, basically every ancient culture on the globe that did mathematics had some version of these formulas: for example, the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, and Mayans.

Naturally, this leads to a simple question: is there a formula for the cubic:

Is there some formula that we can just plug ,

,

, and

to just get the answer? The answer is, Yes, there is a formula. But it’s nasty. The formula was not discovered until 1535 A.D., and it was discovered by a man named Tartaglia. During the 1500s, the study of mathematics was less about the dispassionate pursuit of truth and more about exercising machismo. One mathematician would challenge another: “Here’s my cubic equation; I bet you can’t solve it. Nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah.” Then the second mathematician would solve it and challenge the first: “Here’s my cubic equation; I bet you can’t solve it. Nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah.” And so on. Well, Tartaglia came up with a formula that would solve every cubic equation. By plugging in

,

,

, and

, you get the answer out.

Tartaglia’s discovery was arguably the first triumph of the European Renaissance. The solution of the cubic was perhaps the first thing known to European mathematicians in the Middle Ages that was unknown to the ancient Greeks.

In 1535, Tartaglia was a relatively unknown mathematician, and so he told a more famous mathematician, Cardano, about his formula. Cardano told Tartaglia, why yes, that is very interesting, and then published the formula under his own name, taking credit without mention of Tartaglia. To this day, the formula is called Cardano’s formula.

So there is a formula. But it would take an entire chalkboard to write down the formula. That’s why we typically don’t make students learn this formula in high school; it’s out there, but it’s simply too complicated to expect students to memorize and use.

This leads to the next natural question: what about quartic equations?

The solution of the quartic was discovered less than five years later by an Italian mathematician named Ferrari. Ferrari found out that there is a formula that you can just plug in ,

,

,

, and

, turn the crank, and get the answers out. Writing out this formula would take two chalkboards. So there is a formula, but it’s also very, very complicated.

Of course, Ferrari had some famous descendants in the automotive industry.

So now we move onto my favorite equation, the quintic. (If you don’t understand why it’s my favorite, think about my last name.)

After solving the cubic and quartic in rapid succession, surely there should also be a formula for the quintic. So they tried, and they tried, and they tried, and they got nowhere fast. Finally, the problem was solved nearly 300 years later, in 1832 (for the sake telling a good story, I don’t mention Abel) by a French kid named Evariste Galois. Galois showed that there is no formula. That takes some real moxie. There is no formula. No matter how hard you try, you will not find a formula that can work for every quintic. Sure, there are some quintics that can be solved, like . But there is no formula that will work for every single quintic.

Galois made this discovery when he was 19 years old… in other words, approximately the same age as my students. In fact, we know when wrote down his discovery, because it happened the night before he died. You see, he was living in France in 1832. What was going on in France in 1832? I ask my class, have they seen Les Miserables?

France was torn upside-down in 1832 in the aftermath of the French Revolution, and young Galois got into a heated argument with someone over politics; Galois was a republican, while the other guy was a royalist. More importantly, both men were competing for the hand of the same young woman. So they decided to settle their differences like honorable Frenchmen, with a duel. So Galois wrote up his mathematical notes one night, and the next day, he fought the duel, he lost the duel, and he died.

Thus giving complete and total proof that tremendous mathematical genius does not prevent somebody from being a complete idiot.

For the present, there are formulas for cubic and quartic equations, but they’re long and impractical. And for quintic equations and higher, there is no formula. So that’s why we teach these indirect methods like the Rational Root Test and Descartes’ Rule of Signs, as they give tools to use to guess at the roots of higher-order polynomials without using something like the quadratic formula.

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/QuadraticEquation.html

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CubicFormula.html

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/QuarticEquation.html

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/AbelsImpossibilityTheorem.html

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/QuinticEquation.html

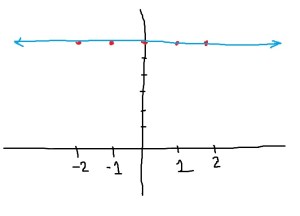

Graphing a function by plugging in points

I love showing this engaging example to my students to emphasize the importance of the various curve-sketching techniques that are taught in Precalculus and Calculus.

Problem. Sketch the graph of .

“Solution”. Let’s plug in some convenient points, graph the points, and then connect the dots to produce the graph.

That’s five points (shown in red), and surely that’s good enough for drawing the picture. Therefore, we can obtain the graph by connecting the dots (shown in blue). So we conclude the graph is as follows.

Of course, the above picture is not the graph of , even though the five points in red are correct. I love using this example to illustrate to students that there’s a lot more to sketching a curve accurately than finding a few points and then connecting the dots.

Engaging students: Solving quadratic equations

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Elizabeth (Markham) Atkins. Her topic, from Algebra II: solving quadratic equations.

D. History: Who were some of the people who contributed to the discovery of this topic?

Factoring quadratic polynomials is a useful trick in mathematics. Mathematics started long ago. http://www.ucs.louisiana.edu/~sxw8045/history.htm stated that the Babylonians “had a general procedure equivalent to solving quadratic equations”. They taught only through examples and did not explain the process or steps to the students. http://www.mytutoronline.com/history-of-quadratic-equation states that the Babylonians solved the quadratic equations on clay tablets. Baudhayana, an Indian mathematician, began by using the equation . He provided ways to solve the equations. Both the Babylonians and Chinese were the first to use completing the square method which states you take the equation

. You take

and divide it by two. After you divide by two you square that number and add it to

and subtract it from

. Even doing it this way the Babylonians and Chinese only found positive roots. Brahmadupta, another Indian mathematician, was the first to find negative solutions. Finally after all these mathematicians found ways of solving quadratic equations Shridhara, an Indian mathematician, wrote a general rule for solving a quadratic equation.

C. Culture: How has this topic appeared in the news?

USA today (http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2007-03-04-teacher-parabola-side_N.htm) had a news article that talks about students who used quadratic equations to cook marshmallows. A teacher had students in teams choose a quadratic equation. The teams then used the quadratic equation choosen to build a device to “harness solar heat and cook marshmallows”. http://www.kveo.com/news/quadratic-equations-no-problem talks about a 6 year old who learned to solve quadratic equations. Borland Educational News (http://benewsviews.blogspot.com/2007/03/memorize-quadratic-formula-in-seconds_3620.html) talks about someone who came up with a song for the quadratic formula, which is a way to solve a quadratic equation. They sing the following words to the tune of Pop Goes the Weasel: “X is equal to negative B plus or minus the square root of B squared minus 4AC All over 2A.” It may be an elementary way to solve the equation, but it sure does work. Mathematics is all around us. It is in our everyday lives. We use it without even knowing it sometimes!

A. Applications: How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Lesson Corner (http://www.lessoncorner.com/Math/Algebra/Quadratic_Equations) is an excellent resource for finding lesson plans and activities for quadratic equations. One lesson (http://distance-ed.math.tamu.edu/peic/lesson_plans/factoring_quadratics.pdf) talking about engaging the students with a game called “Guess the Numbers”. The students are given two columns, a sum column and a product column. They are then to guess the two numbers that will add to get the sum and multiply to get the product. This is an excellent game because it gets the students going and it is like a puzzle to solve. Learn (http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/2981) has a lesson plan for a review of quadratic equations. The students are engaged by playing “Chutes and Ladders”. The teacher transformed it. The procedures are as follows:

- Draw a card.

- Roll the dice.

- If you roll a 1 or a 6, then solve your quadratic equation by completing the square.

- If you roll a 2 or 5, then solve your quadratic equation by using the quadratic formula.

- If you roll a 3, then solve your quadratic equation by graphing.

- If you roll a 4, then solve your quadratic equation by factoring if possible. If not, then solve it another way.

- If you solve your equation correctly, then you may move on the board the number of spaces that corresponds to your roll of the die.

- If you answer the question incorrectly, then the person to your left has the opportunity to answer your question and move your roll of the die.

- The first person to reach the end of the board first wins the game!

- Good luck!!

I think this is an excellent idea because it brings back a little of the students’ childhood!

Engaging students: Factoring quadratic polynomials

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Kelsie Teague. Her topic, from Algebra I and II: factoring quadratic polynomials.

What interesting things can you say about the people who contributed to the discovery and/or the development of the topic?

In Renaissance times, polynomial factoring was a royal sport. Kings sponsored contests and the best mathematicians in Europe traveled from court to court to demonstrate their skills. Polynomial factoring techniques were closely guarded secrets.

http://www.ehow.com/info_8651462_history-polynomial-factoring.html

When reading this article, I found the fact that this topic was considered a royal sport very interesting. Students would also find that interesting because it would get their attention with the fact that kings thought this was very important. We could even have our own royal game for it. I think we could start off with a scavenger hunt to work on factoring just basic integers. Also, I think we could use the same idea to start the explore except to do it backwards and give them the polynomial already factored and have them FOIL it and get their polynomial. I want to see if they can see how to do it the other way around without being taught how. This game could show them that factoring is just the reverse of foiling.

How can technology (YouTube, Khan Academy [khanacademy.org], Vi Hart, Geometers Sketchpad, graphing calculators, etc.) be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

I looked up factoring quadratic polynomials on Khan Academy and I found some really great videos. They have videos that show detail steps and also after a few videos they have parts where you can practice what you just watched and see if you understand it. This website is great for at home practice or in class practice because with the practice sections it tells you if you are correct or not and will also give you hints if you don’t know where to start. Also, if you don’t have a clue how to do the problem given, you can hit “show me solution” and it will redirect you to a similar problem in a video to help out. I think this website is a great tool to let students know about to learn and practice.

Also I found a great video on YouTube it’s a rap about factoring that would certainly get gets engaged.

Curriculum

Students first learn about the basic idea of factoring in elementary school and continue to learn and use this topic all the way through college. You need to factor polynomials in many different contexts in mathematics. It’s a fundamental skill for math in general and can make other calculations much easier. You use factoring for finding solutions of various equations, and such equations can come up in calculus when find maxima, minima, inflection points, solving improper integrals, limits, and partial fractions. Students will need to know factoring all the way up in to their higher-level math classes in college, and also be able to use it in a career that is related to engineering, physics, chemistry and computer science.