In this series of posts, I’d like to describe what I tell my students on the very first day of Calculus I. On this first day, I try to set the table for the topics that will be discussed throughout the semester. I should emphasize that I don’t hold students immediately responsible for the content of this lecture. Instead, this introduction, which usually takes 30-45 minutes, depending on the questions I get, is meant to help my students see the forest for all of the trees. For example, when we start discussing somewhat dry topics like the definition of a continuous function and the Mean Value Theorem, I can always refer back to this initial lecture for why these concepts are ultimately important.

I’ve told students that the topics in Calculus I build upon each other (unlike the topics of Precalculus), but that there are going to be two themes that run throughout the course:

- Approximating curved things by straight things, and

- Passing to limits

I then applied these two themes to find the speed of a falling object at impact.

I now switch to a second, completely unrelated (or at least it seems completely unrelated) problem.

Problem #2. Find the area under the parabola

between

and

.

I draw the picture and ask, “OK, what formula from geometry can we use for this one?” Stunned silence.

I say, “Of course you can’t do this yet. This is a curved thing. Back in high school geometry, you learned (with one exception) the areas of straight things. What straight things had area formulas in high school geometry?” I’ll always get rectangles and triangles as responses. Occasionally, someone will volunteer parallelogram or rhombus or kite.

So I ask the leading question, which of these shapes is easiest? Students always answer, “Rectangles.” Which then leads me to the next question: How can we approximate the area under a parabola with a bunch of rectangles?

Again, stunned silence. I let my students think about it for at least a minute, sometimes two minutes. Hopefully, one student will volunteer the answer that I want, though occasionally I’ll have to coax it out of them.

Eventually either a student volunteers (or else I tell the class) that we ought to use a bunch of thin rectangles. For starters, I’ll use five rectangles and a very rough sketch on the board.

I’ll start with the right-most rectangle… what is its area? Students immediately see that the width is , but the length takes a little bit more thought. And I make my students figure it out without me giving them the answer. Eventually, someone notices that the height is simply

, so that the rightmost rectangle has an area of

.

I then move to the rectangle that’s second to the right. This also has a width of , but the height is

. So the area is

.

Eventually, we get that the sum of the areas is . Students can easily see that this is a decent approximation to the area under the parabola, but it’s a bit too large.

I then ask the same question that I had before: how can we get a better approximation? Students will usually volunteer either “More rectangles” or “Thinner rectangles,” which of course are logically equivalent. I then proceed with 10 equal-width rectangles. Occasionally, a student volunteers that perhaps we should use thinner rectangles only on the right side of the figure, which of course is a very astute observation. However, I tell my class that, for the sake of simplicity, we’ll stick with rectangles of equal width.

With ten rectangles (and I redraw the picture with ten thin rectangles), the approximation is quickly found to be

I like using ten rectangles, as that’s probably the largest number that can be handled in class without a calculator (until the very last step of adding up the areas).

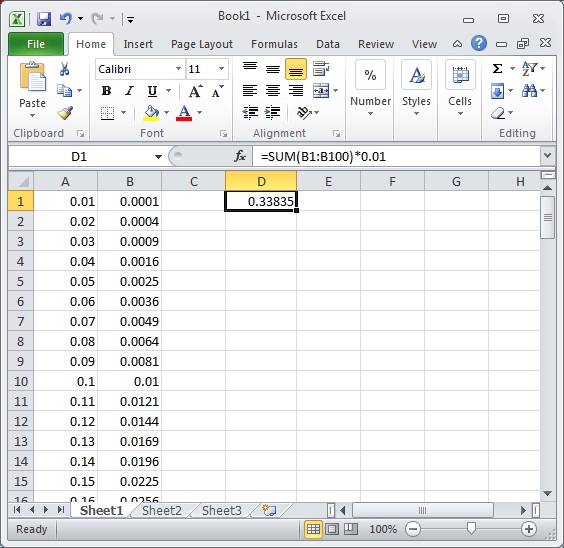

By now, the class sees what the next steps are: take more and more rectangles. At this point, I’ll resort to classroom technology to make the process a little quicker. I personally prefer Microsoft Excel, though other software packages can be used for this purpose. For rectangles, the class quickly sees that the sum of the rectangles is

My class can see that the answer is still too large, but it’s certainly closer to the correct answer.

I’ll then tell the class that this is another example of passing to limits, the second theme of calculus. I’ll describe this more fully in the next post.