The following problem in differential equations has a very practical application for anyone who has either (1) taken out a loan to buy a house or a car or (2) is trying to pay off credit card debt. To my surprise, most math majors haven’t thought through the obvious applications of exponential functions as a means of engaging their future students, even though it is directly pertinent to their lives (both the students’ and the teachers’).

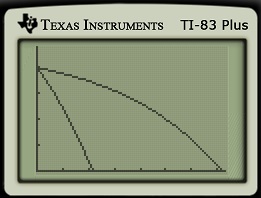

You have a balance of $2,000 on your credit card. Interest is compounded continuously with a rate of growth of 25% per year. If you pay the minimum amount of $50 per month (or $600 per year), how long will it take for the balance to be paid?

In previous posts, I approached this problem using differential equations. There’s another way to approach this problem that avoids using calculus that, hypothetically, is within the grasp of talented Precalculus students. Instead of treating this problem as a differential equation, we instead treat it as a first-order difference equation (also called a recurrence relation):

The idea is that the amount owed is multiplied by a factor (which is greater than 1), and from this product the amount paid is deducted. With this approach — and unlike the approach using calculus — the payment period would be each month and not per year. Therefore, we can write

Notice that the meaning of the 25% has changed somewhat… it’s no longer the relative rate of growth, as the 25% has been equally divided for the 12 months.

A full treatment of the solution of difference equations belongs to a proper course in discrete mathematics. However, this particular difference equation can be solved in a straightforward fashion that should be accessible to talented Precalculus students. Let’s use the above recurrence relation to try to find a pattern. For

A full treatment of the solution of difference equations belongs to a proper course in discrete mathematics. However, this particular difference equation can be solved in a straightforward fashion that should be accessible to talented Precalculus students. Let’s use the above recurrence relation to try to find a pattern. For , we find

.

For , we find

For , we find

At this point, we can probably guess a pattern:

Using the formula for a finite geometric series, this simplifies as

.

Indeed, though I won’t do it here, this can be formally proven using mathematical induction.