The following problem appeared in Volume 97, Issue 3 (2024) of Mathematics Magazine.

Two points

and

are chosen at random (uniformly) from the interior of a unit circle. What is the probability that the circle whose diameter is segment

lies entirely in the interior of the unit circle?

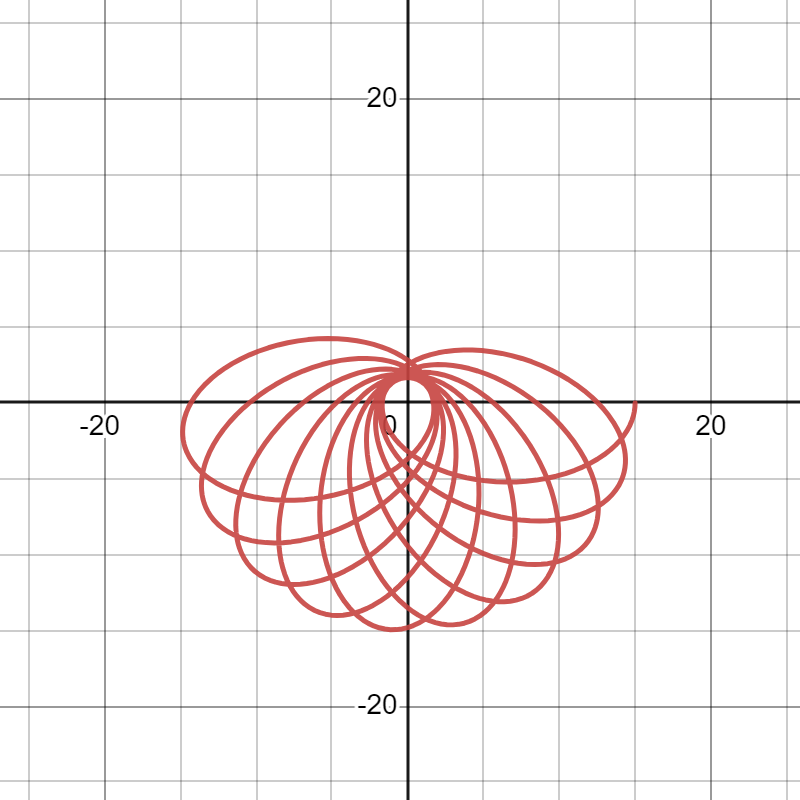

As discussed in a previous post, I guessed from simulation that the answer is . Naturally, simulation is not a proof, and so I started thinking about how to prove this.

My first thought was to make the problem simpler by letting only one point be chosen at random instead of two. Suppose that the point is fixed at a distance

from the origin. What is the probability that the point

, chosen at random, uniformly, from the interior of the unit circle, has the desired property?

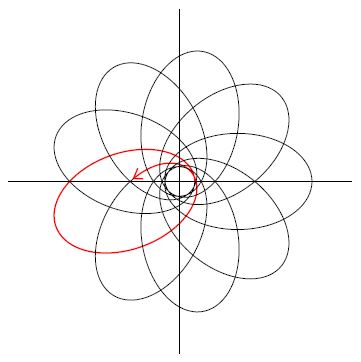

My second thought is that, by radial symmetry, I could rotate the figure so that the point is located at

. In this way, the probability in question is ultimately going to be a function of

.

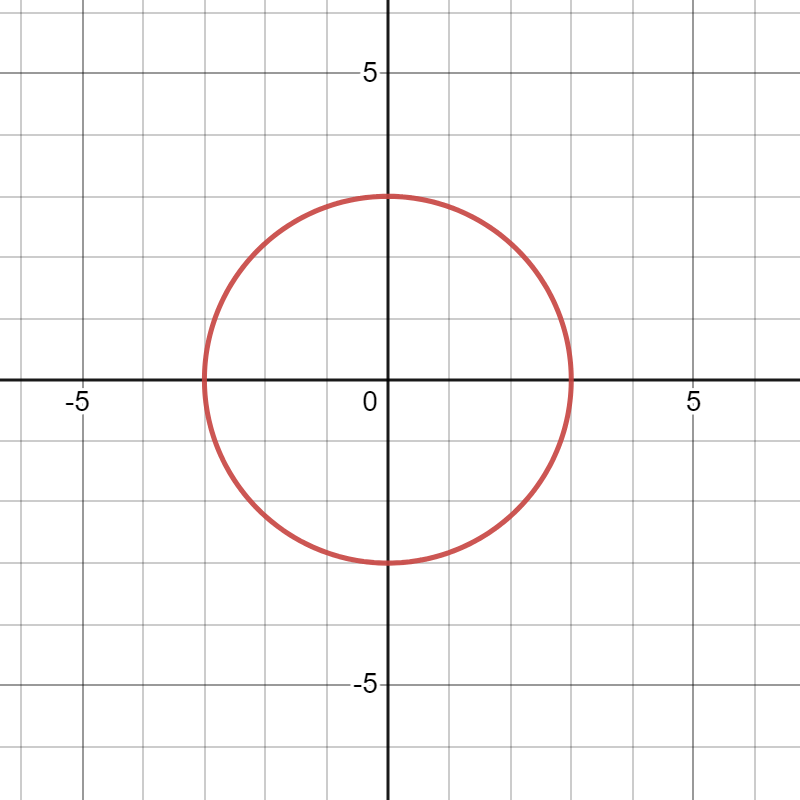

There is a very nice way to compute such probabilities since is chosen at uniformly from the unit circle. Let

be the set of all points

within the unit circle that have the desired property. Since the area of the unit circle is

, the probability of desired property happening is

.

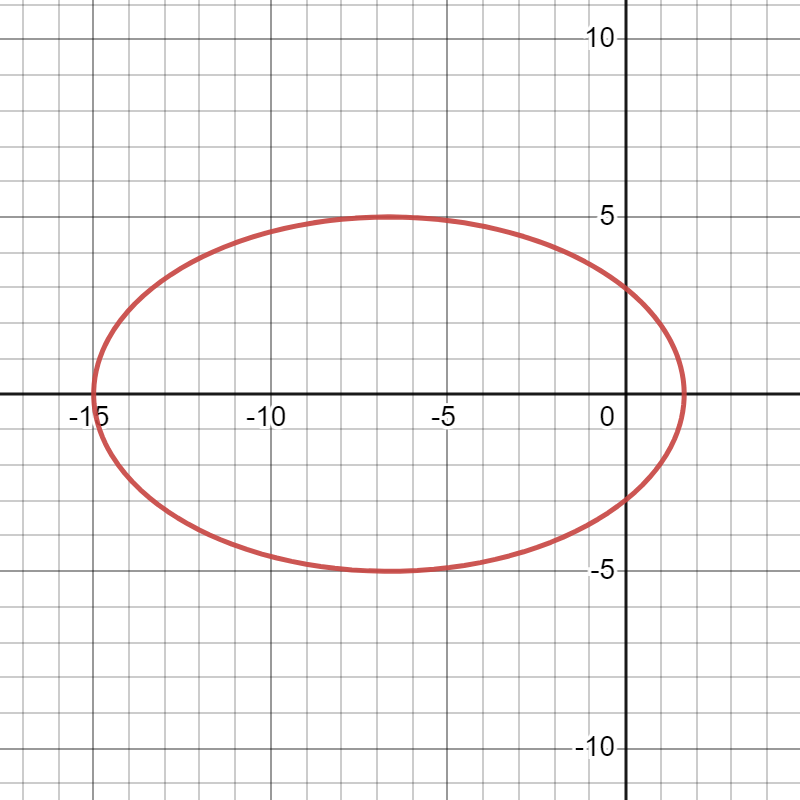

Based on the simulations discussed in the previous post, my guess was that was the interior of an ellipse centered at the origin with a semimajor axis of length

and a semiminor axis of length

. Now I had to think about how to prove this.

As noted earlier in this series, the circle with diameter will lie within the unit circle exactly when

, where

is the midpoint of

. So suppose that

has coordinates

, where

is known, and let the coordinates of

be

. Then the coordinates of

will be

,

so that

and

.

Therefore, the condition (again, equivalent to the condition that the circle with diameter

lies within the unit circle) becomes

,

which simplifies to

.

When I saw this, light finally dawned. Given two points and

, called the foci, an ellipse is defined to be the set of all points

so that

, where

is a constant. If the coordinates of

,

, and

are

,

, and

, then this becomes

.

Therefore, the set is the interior of an ellipse centered at the origin with

and

. Furthermore,

is the semimajor axis of the ellipse, while the semiminor axis is equal to

.

At last, I could now return to the original question. Suppose that the point is fixed at a distance

from the origin. What is the probability that the point

, chosen at random, uniformly, from the interior of the unit circle, has the property that the circle with diameter

lies within the unit circle? Since

is a subset of the interior of the unit circle, we see that this probability is equal to

.

In the next post, I’ll use this intermediate step to solve the original question.