There are two apparently different definitions of a logarithm that appear in the secondary mathematics curriculum:

- From Algebra II and Precalculus: If

and

and  , then

, then  is the inverse function of

is the inverse function of  .

.

- From Calculus: for

, we define

, we define  .

.

The connection between these two apparently different ideas begins with the following theorem, which was proven in the few previous posts.

Theorem. Let  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  has the following four properties:

has the following four properties:

for all

for all

is continuous

is continuous

Then  for all

for all  .

.

At this point, we have provided enough groundwork to make the connection between these two different ways of viewing a logarithm.

At this point, we have provided enough groundwork to make the connection between these two different ways of viewing a logarithm.

Let’s define the function (for  )

)

.

.

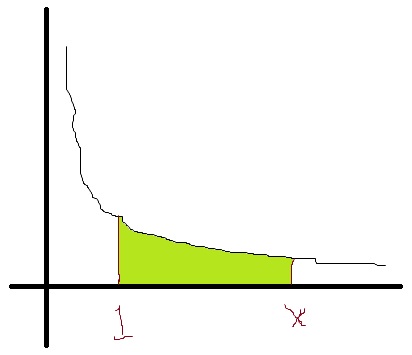

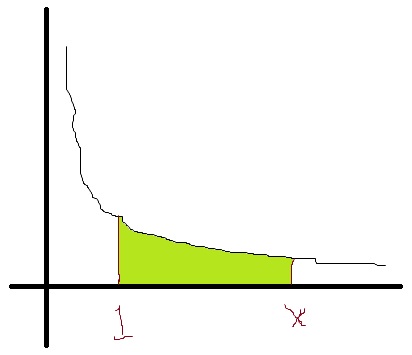

I’ll illustrate this with the appropriate area under the hyperbola  . (Please forgive the crudeness of this drawing; I’m only using Microsoft Paint.)

. (Please forgive the crudeness of this drawing; I’m only using Microsoft Paint.)

So if

So if  is the right-hand limit, then

is the right-hand limit, then  is just the shaded area under the curve.

is just the shaded area under the curve.

Often, someone will interject, “Hey, I know how to do that… it’s just the natural logarithm of  .” To which I will respond, “Yes, that’s true. But why is it the natural logarithm of

.” To which I will respond, “Yes, that’s true. But why is it the natural logarithm of  ?” I have yet to encounter a student who can immediately answer this question (which, of course, is the whole point of me presenting this in class). In other words, I want my students to realize that, many semesters ago, they pretty much accepted on faith that the above integral is equal to

?” I have yet to encounter a student who can immediately answer this question (which, of course, is the whole point of me presenting this in class). In other words, I want my students to realize that, many semesters ago, they pretty much accepted on faith that the above integral is equal to  , but they were never told the reason why. And now — several semesters after completing the calculus sequence — we’re finally going over the reason why.

, but they were never told the reason why. And now — several semesters after completing the calculus sequence — we’re finally going over the reason why.

To start, I’ll say, “OK,  is defined as an integral. That means that it must have…” Someone will usually volunteer, “A derivative.” I’ll respond, “That’s right. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus says that this function is differentiable. So, if something is differentiable, then it also must be…” Someone will usually volunteer, “Continuous.” My response: “That’s right. So

is defined as an integral. That means that it must have…” Someone will usually volunteer, “A derivative.” I’ll respond, “That’s right. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus says that this function is differentiable. So, if something is differentiable, then it also must be…” Someone will usually volunteer, “Continuous.” My response: “That’s right. So  must be continuous. So that’s Property 4: this function is continuous.” I’ll continue: “Let’s see if we can get the other properties.”

must be continuous. So that’s Property 4: this function is continuous.” I’ll continue: “Let’s see if we can get the other properties.”

I’ll next move to Property 1, as it’s the next easiest. I’ll ask the class, “Can you prove to me that  ?” After a moment of thought, someone will notice that

?” After a moment of thought, someone will notice that

.

.

must be equal to  since the left and right endpoints of the integral are the same.

since the left and right endpoints of the integral are the same.

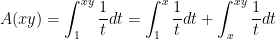

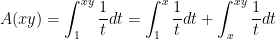

Then I’ll skip over to Property 3, which requires a little more thought. To begin, we can write

.

.

Before proceeding, I’ll ask my class why the above line has to be true. After a couple moments, someone will volunteer something like “The area from  to

to  plus the area from

plus the area from  to

to  has to be equal to the area from

has to be equal to the area from  to

to  .”

.”

I’ll then say something like, “We can simplify one of the integrals on the right-hand side right away. Which one?” Students quickly see that the first integral on the right,  , is of course equal to

, is of course equal to  . So then I’ll ask, “So what do I want the last integral to be equal to?” Students look back at Property 3 and answer, “That should be

. So then I’ll ask, “So what do I want the last integral to be equal to?” Students look back at Property 3 and answer, “That should be  .

.

So, if we can show the final integral is equal to  , we have established Property 3. To this end, I will perform a somewhat unusual looking

, we have established Property 3. To this end, I will perform a somewhat unusual looking  substitution:

substitution:

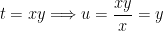

In this formula, I encourage my students to think of  as the old variable of integration,

as the old variable of integration,  as the new variable of integration, and

as the new variable of integration, and  as an unknown number that is constant. So I’ll say parenthetically, “If

as an unknown number that is constant. So I’ll say parenthetically, “If  , how do we find

, how do we find  ?” Students of course answer, “

?” Students of course answer, “ must be

must be  .” So I’ll follow up: “If

.” So I’ll follow up: “If  , how do we find

, how do we find  ?” Students get the idea:

?” Students get the idea:

So to complete the  substitution, we must adjust the limits of integration. For the lower limit,

substitution, we must adjust the limits of integration. For the lower limit,

For the upper limit,

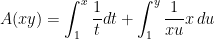

So we can now complete the  substitution of the second integral:

substitution of the second integral:

.

.

.

.

.

.

Students recognize that, except for the variable of integration, the last integral is just  , which leads to the punch line

, which leads to the punch line

In other words, we have established that the function  satisfies Property 3.

satisfies Property 3.

So the only property left is Property 2. To that end, let’s define the number  so that the area in green above is equal to 1. There’s no other way to describe this number…. we just increase

so that the area in green above is equal to 1. There’s no other way to describe this number…. we just increase  far enough along the

far enough along the  axis until the area under the hyperbola is equal to 1. Wherever this happens, that’s the number that we’ll call

axis until the area under the hyperbola is equal to 1. Wherever this happens, that’s the number that we’ll call  . So, by definition,

. So, by definition,  .

.

Therefore, by the above theorem, we conclude that  , written more simply as

, written more simply as  .

.

To summarize: using the above theorem, we are able to establish that the integral  has all of the properties of a logarithm and therefore must be a logarithmic function. The only catch is that we had to define

has all of the properties of a logarithm and therefore must be a logarithmic function. The only catch is that we had to define  to be the base of this logarithm through an unusual definition concerning the area under a hyperbola.

to be the base of this logarithm through an unusual definition concerning the area under a hyperbola.

Of course, this is not the “standard” definition of  that is usually encountered in a Precalculus class. More on these different definitions in a future series of posts.

that is usually encountered in a Precalculus class. More on these different definitions in a future series of posts.

One more pedagogical note: My experience is that I can cover the content of the first 7 posts of this series in a single 50-minute lecture and still keep my students’ attention. Naturally, I’ll recapitulate the highlights of this logical development at the start of the next lecture by way of review, as this is an awful lot to absorb at once.

are related to each other. The number

is usually introduced at two different places in the mathematics curriculum:

dollars are invested at interest rate

for

years with continuous compound interest, then the amount of money after

years is

.

is defined to be the number so that the area under the curve

from

to

is equal to

, so that

.

. However, compound interest usually appears earlier in the mathematics curriculum than definite integrals, and so an informal definition of

is given at that stage of the curriculum.

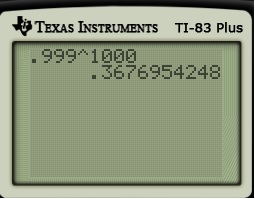

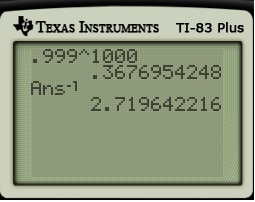

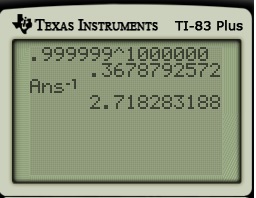

when interest is compounded

times a year. In a couple of days, I’ll discuss how the above formula naturally leads to the formula

when interest is continuously compounded. Today, I’d like to give some pedagogical thoughts about both formulas.

a few times and see if a pattern can be developed. However, my observation is that college students have no memory of being taught how the compound interest formula

can be seen as a natural consequence of the simple interest formula. In other words, they’d just use the compound interest formula without having any conceptual understanding of where the formula came from.